Ironclads vs. Fort: Drewry’s Bluff and Fort Darling

On a steamy Virginia day this summer, I visited the site along the west bank of the James River where a small-scale but significant engagement took place on May 15, 1862, during the Virginia Peninsula campaign. Fort Darling on Drewry’s Bluff is a lovely, isolated spot any time of year encompassing 42 wooded acres of the Richmond National Battlefield Park twelve road miles south of the state capitol.

On a steamy Virginia day this summer, I visited the site along the west bank of the James River where a small-scale but significant engagement took place on May 15, 1862, during the Virginia Peninsula campaign. Fort Darling on Drewry’s Bluff is a lovely, isolated spot any time of year encompassing 42 wooded acres of the Richmond National Battlefield Park twelve road miles south of the state capitol.

To get there, you wind through a residential and light industrial area off I-95 or 301. (Ask for directions to Fort Darling in Google Map.) Park and walk a mile over a cool forest trail to the fort on the clifftop with a commanding view downriver unblemished by modernity. Extensive earthworks and artillery emplacements are remarkably well preserved, shaded by mature trees with winding paths and excellent interpretive signage.

Sight over the barrel of the big Columbiad seacoast gun and imagine Union gunboats and ironclads—including the USS Monitor—chugging round the sharp bend 90 feet below and a mile downriver, belching smoke and blasting shots while your crew scrambles to reply in kind. You are revisiting the ironclad vs. fort battle of Drewry’s Bluff (not to be confused with the infantry battle of the same name during the Bermuda Hundred Campaign two years later).

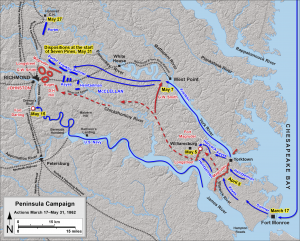

Two months previously, March 8-9, 1862, the Rebel ironclad CSS Virginia (aka Merrimack) obliterated two Union warships in Hampton Roads, damaged several others, and fought the revolutionary Monitor to a standstill. Fear of the Virginia loomed over local waters while Major General George B. McClellan commenced his invasion of the Peninsula.

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles declined to commit Monitor to another engagement with Virginia–risking serious damage and exposing his many wooden vessels in Hampton Roads as easy pickings–unless absolutely necessary. Monitor remained in a strictly defensive posture. Welles could not guarantee troop and supply transport or heavy artillery support up the James and York Rivers on the water flanks of the Army of the Potomac.

McClellan found his options constricted, which reinforced his penchant for caution. He shifted supply routes from the James to the York rivers, abandoned plans to amphibiously envelop the Yorktown entrenchments, and proceeded with a massive land advance requiring a two-week siege employing slow-moving siege guns in place of big shipboard weapons.

Having finally pushed the Confederates out of Yorktown (April 5) and Williamsburg (May 5), the general’s mighty host was inching toward Richmond and the coming clash with General Joe Johnston at Seven Pines near the end of May. McClellan urged the navy to send gunboats up the James to disrupt enemy supply lines.

Frustrated by this glacial advance and the continued threat of the Virginia, the commander in chief decided to take the field. Abraham Lincoln arrived at Fort Monroe in the Revenue Cutter Miami on May 6 to see for himself. That evening, Commander John Rodgers, captain of the brand-new armored gunboat USS Galena, paid an impromptu visit to the president who greeted him warmly from his bed aboard Miami.

The commander reported to his wife that he had “expatiated” to Lincoln a “great opening for a Naval movement up the James River,” which idea was immediately approved. Rodgers anticipated orders to proceed with Galena and two wooden gunboats, “to attack the [river] batteries, maybe to take Richmond-Quien sabe.”

The Confederate army on the Peninsula must be fed through the river, Rodgers continued. “If I can cut off their supplies, they will starve. I can stop their retreat by water, cut off the communication except by impassible roads.” He must, however, get around the Virginia still hovering in Hampton Roads.[1]

Then Union forces under the commander in chief’s direct supervision recaptured Norfolk and the Gosport Shipyard, Virginia’s homebase. The ironclad had nowhere to go and faced overwhelming opposition, so her crew blew her up on May 11. Only one major obstacle barred the water route to the Rebel capital—Drewry’s Bluff and Fort Darling.

Confederates scrambled to complete the works mounting one 10-inch and two 8-inch Columbiad seacoast guns and field pieces capable of dumping rounds down into the river channel that was too narrow for evasive maneuvering. Below the bluff, sunken steamers, pilings, debris, and boats linked by chains obstructed the way. Six more large guns occupied pits just upriver.

The Southside Heavy Artillery manned the batteries led by Captain Augustus H. Drewry (owner of the property bearing his name) and joined by sailors of Virginia’s former gun crews eager to continue the fight. Confederate Navy Commander Ebeneezer Farrand supervised the defenses. Rifle pits with infantry sharpshooters lined the banks.

Commander Rogers proceeded upriver in Galena accompanied by wooden gunboats Port Royal and Aroostook. They were joined by Monitor and the experimental iron gunboat Naugatuck.

As the war began the year before, three novel ironclads had been hurriedly constructed for a navy with no experience with such vessels. The first two—Galena and the armored frigate USS New Ironsides—were traditional wooden hull forms with sailing rigs, steam propulsion, multi-gun broadside batteries, and iron cladding.

They were intended primarily to counter the Royal Navy’s expanding fleet of powerful, iron warships should the British decide to intervene in the conflict, which was deemed a distinct possibility at the time. New Ironsides was the largest, comparable to British and French seagoing counterparts. She would be successful operating mainly in the blockading fleet around Charleston.

Galena was smaller, a compromise in size, armor, and armament to operate both at sea and in harbors, bays, and large rivers. Her most unique feature was an untried system of interlocking iron hull planks 2 to 3 inches thick. Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough, commanding the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, was not impressed: “She is a sad affair. Her projectors & builders ought to be ashamed of her.”[2]

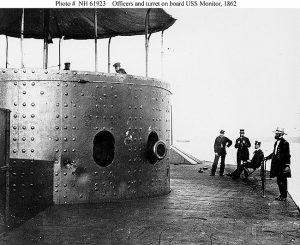

The third new ironclad was Monitor—a small, iron-plated raft with a two-gun battery in a revolving iron turret. Senior navy officers had regarded her with low confidence as an experiment that might prove useful in opposing the Virginia, also under construction in late 1861.

The third new ironclad was Monitor—a small, iron-plated raft with a two-gun battery in a revolving iron turret. Senior navy officers had regarded her with low confidence as an experiment that might prove useful in opposing the Virginia, also under construction in late 1861.

On the morning of May 15, 1862, the five Union warships reached Drewry’s Bluff. Galena closed to about 600 yards, as near to sunken obstructions as possible. She let go her anchor, swung broadside to the stream—which was about twice as wide as the ship was long—and at 7:45 a.m., opened fire.

With her shallower draft, Monitor tried to get closer, but at that proximity, her guns could not elevate to the high batteries, so she backed off to longer, less accurate, range. Naugatuck’s single 100-pounder Parrott rifle burst at the breech, putting her out of action. The wooden gunboats hovered back beyond danger.

Ironclads and fort blasted away until, at 11:05 a.m., Rodgers disengaged. Galena was not shot proof, he reported. “Balls came through, and many men were killed with fragments of her own iron.” Thirteen shots penetrated. Galena’s inward-slanting sides (called the “tumblehome”) were designed to deflect shots, but unfortunately, rounds plunging from the heights hit square and penetrated.[3]

A few glancing balls blew holes in the thin top-deck plating, showering iron fragments below. Other rounds hit the waterline, broke the thin iron planks, and stuck in wood backing. The hull was severely damaged; thirteen sailors were killed and eleven wounded. They were almost out of ammunition.

“The fire of the enemy was remarkably well directed,” wrote Monitor’s commanding officer, Lt. William Jeffers, “but vainly, towards this vessel.” One solid 8-inch shot hit square on the turret; two struck the side armor forward of the pilothouse. “Neither caused any damage beyond bending the plates. I am happy to report no casualties.”

“The action was most gallantly fought against great odds,” he continued, “and with the usual effect against earthworks.” Rebel gunners would just take shelter from Union shots and reman their guns when fire slackened. “It was impossible to reduce such works, except with the aid of a land force.”[4]

Jeffers concluded that such an operation, “requires the concurrence of many favorable contingencies.” If Monitor could approach within a couple hundred yards of an earthen fort near water level, “she has sufficient endurance to stand its fire until she can dismount its guns, one by one,” or in the case of masonry, to “quarry a hole into the face of the wall until it tumbled down by the superincumbent weight.”

Monitor was, however, hampered by a slow rate of fire. The turret must revolve exposed gun ports away to load, and then back to fire while the enemy in his embrasures more quickly reloads and takes aim. The ironclad could just run on by the fort; she was invulnerable, he thought, to shot of 8-inch and lower calibers while “monster calibres” had almost no chance of hitting a moving target.

Jeffers concluded that—the Hampton Roads engagement and exploits of iron-plated western gunboats notwithstanding—protecting guns and gunners with iron “does not, except in special cases, compensate for the greatly diminished quantity of artillery, slow speed, and inferior accuracy of fire [of ironclads], and that, for general purposes, wooden ships, shell guns, and forts, whether for offence or defense, have not yet been superseded.”[5]

Commander Rodgers suggested the army should be landed on either bank of the James within ten miles of Richmond and envelop Fort Darling. “We command City Point, and are ready to co-operate with a land force in an advance upon Petersburg,” although it would be necessary to protect the crews from sharpshooters. “They annoyed us.”

Had the army done this, Rodgers later wrote, the Rebel capital would have fallen in spring 1862. The navy (including Galena) did provide gunfire support to McClellan at the battle of Malvern Hill and evacuated the army from Harrison’s Landing as he abandoned the Peninsula.

Under supervision of Confederate Navy Captain Sydney Smith Lee (Robert E. Lee’s brother), the site was expanded and strengthened into a permanent fort with chapel, barracks, and officers’ quarters. The facility also housed the Confederate States Naval Academy with the training ship CSS Patrick Henry anchored in the river, and the Confederate Marine Corps instruction camp.

Fort Darling would defy Union conquest until abandoned as Richmond defenses collapsed in spring 1865. Soldiers, sailors, and marines fled westward with the Army of Northern Virginia, fought in the (appropriately named) battle of Sailor’s Creek, and surrendered at Appomattox.

A boat passed the fort on April 4 with President Abraham Lincoln and his son Tad on the way up to visit Richmond. City dwellers had enjoyed picnicking and socializing with the garrison at Fort Darling during the war. It still is a great place to visit.

[1] Robert Erwin Johnson, Rear Admiral John Rodgers, 1812-1882 (Annapolis, 1967), 196-197.

[2] Confidential Correspondence of Gustavus Vasa Fox, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, 1861–1865, 2 vols. (New York, 1920), 1:265.

[3] Report of the Secretary of the Navy in Relation to Armored Vessels (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1864), 25.

[4] Ibid., 26.

[5] Ibid., 29.

This is a nice site to visit, easy to get to.

Excellent summary of a battle that needs more appreciation. Considering what had happened at New Orleans a few weeks earlier, Rodgers had cause for optimism. I also agree with his assessment of what would have happened had McClellan detached some troops.

“A ship’s a fool to fight a fort.” Horatio Nelson. An old adage proved time and again, including at Fort Darling.

But in 2022 there are few active “fixed fortifications” anywhere in the world (British Gibraltar comes to mind) as forts became obsolete due to improved accuracy and increased power of munitions. That tipping point, with ships becoming superior to forts, occurred during the Civil War.

Yep. Steam power and rifled cannon (not the mention the airplane later) gradually made Nelson’s advice obsolete.

Thank you for this post, Dwight. I have visited Drewry’s Bluff twice.