Most Formidable Engine of Destruction: Torpedo Boat “Spuyten Duyvil”

“Your little torpedo boats should be able to whip a ram apiece,” wrote Admiral David D. Porter to the commander of his James River Division in January 1865.[1] One he had in mind was the steam-driven, iron armored, semi-submersible, rapid firing (relatively) spar-torpedo boat USS Spuyten Duyvil. She was to be deployed against powerful Confederate ironclad rams threatening the huge City Point supply base that sustained the armies besieging Petersburg.

The admiral undoubtedly recalled the dramatic sinking of the steam frigate USS Housatonic in February 1864 by the Confederate submarine Hunley, and the destruction in October 1864 of the ironclad CSS Albemarle by Lieutenant William B. Cushing in a 30-foot steam launch with a 14-foot spar torpedo projecting from the bow. In both cases, a small and lightly armed craft manned by a few men neutralized a massive warship by extending explosives on the end of a boom and detonating them under the hull, a good example of tactical asymmetric warfare.

For arguably the first time in history, navies on both sides of a major conflict feverously sought technological and industrial innovation as a primary strategy. Many proposals were duds, even whacky. Rubber ship armor for example. Some experiments like USS Monitor achieved immortality. Others, which earned no fame and are mostly forgotten, are nevertheless fascinating as illustrations of the times and as precursors of future developments.

Both contestants developed torpedo boats in various forms without much other success. But Spuyten Duyvil was a machine-age concoction, unique in design and complexity. An 1868 treatise on submarine warfare dubbed her “the most formidable engine of destruction for naval warfare now afloat.”[2] Thanks to a patent application of March 1865[3] and an article from the British magazine “Engineering” of October 1866,[4] we have details.

The vessel was designed by naval architect Samuel M. Pook who also conceived the city-class ironclads—known as “Pook turtles” for their distinctive outline—that became the backbone of the Union Mississippi River Squadron. The torpedo laying machinery was designed and patented by Captain William W. W. Wood, Chief Engineer, USN, who also fitted out Lt. Cushing’s torpedo launch used against Albemarle.

Spuyten Duyvil was built in New Haven, Connecticut, in three months of late 1864 and deployed to the James River. The name is of Dutch origin after the eponymous Bronx neighborhood of New York City. It might be translated—appropriately—as “Spouting Devil” or “Spewing Devil” originally referring to a local stream disgorging perilous currents into the Hudson.

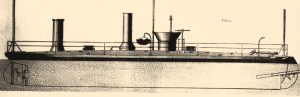

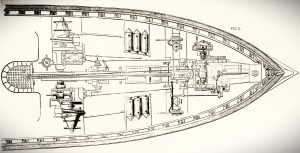

According to the British article, the boat—84 feet long, 21 in beam—had heavy timber framing armored with 1-inch iron plates on deck and sides to the waterline. The cylindrical pilothouse was 5 feet in outside diameter, almost 4 feet tall, weighed 25,000 pounds, and was protected by 1-inch plate iron in 12 layers. (Another source states the armor was 3 inches on deck, and 5 inches on sides and pilothouse.[5]) Twenty-three officers and enlisted manned the machinery-jammed interior with 7 feet of headroom.

The humped deck sat 3 to 4 feet above the surface in normal cruising mode giving Spuyten Duyvil a 7 ½ foot draft. Internal ballast tanks could be flooded by centrifugal steam pumps immersing her to the deck edge, increasing draft to 9 feet, and providing additional protection from shot and shell. Speed was 9 miles per hour, reduced to 3 or 4 when immersed. She was said to be quite noiseless.

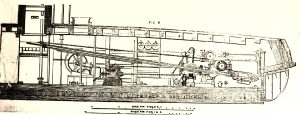

The most distinctive feature was the complex weapon delivery system employing an extensible and reloadable spar. Two hinged iron door flaps on the bottom of the bow opened or closed by attached chains and a hand winch. Behind them was an iron reservoir accessible through a hatch on top and floodable through a sluice valve.

The 20-foot spar extended from inside the reservoir back through a watertight ball-and-socket joint and then through a steam-driven crosshead with trunnions that slid in vertical side rails and a horizontal screw shaft allowing lateral motion. Thus, the spar could be aimed through limited arcs in elevation and train like a cannon.

Chains attached to both ends of the spar led to steam winch drums. Hauling on the deployment chain while easing the recovery chain extended the spar forward and the reverse to recover it. A casing on the end of the tubular spar held the torpedo with a release mechanism. When the spar was pulled back, a rod inside the tube remained partially extended, which opened the release mechanism and eject the torpedo from the casing.

Theoretically, the boat could deploy torpedoes with up to 400 pounds of black powder, but in practice, those used contained just 60 pounds. The released torpedo—with air pockets making it slightly lighter than water—ascended with point down to rest against the target.

Within each torpedo casing was a tube with a percussion cap at the bottom in the powder chamber and a grapeshot at the top held in place by a pin extending through the casing wall with an eye. A cord was attached to the eye of the pin leading back to the end of the spar with a length set as desired, usually about 20 feet. As the spar was hauled in, the cord pulled the pin firing the weapon.

Steps to deploy a torpedo: 1) open bow flaps, 2) raise sluice gate, flood reservoir, 3) extend spar, 4) eject torpedo, 5) haul in spar, firing torpedo 6) close sluice gate, 7) pump out reservoir (about 4 seconds), 8) load new torpedo through hatch, 9) repeat. According to design specs, this cycle could be executed every three minutes.

On the night of January 23, 1865, those Rebel ironclads snuck down the James only to be repulsed in the battle of Trent’s Reach by Federal shore batteries, one Monitor-class warship, and the treacherous river. To Admiral Porter’s frustration, Spuyten Duyvil was not in position to confront and destroy them. What if she had been?

Destruction of Housatonic and Albemarle demonstrated that a torpedo exploding upward and inward beneath the hull of even the strongest vessel was a near certain single-shot mortal blow. The trick was to deploy the weapon and survive. Hunley sank Housatonic and immediately went to the bottom with all hands for reasons unknown then and still not clear.

The submarine was less than half the size and much lighter than Spuyten Duyvil, essentially a hollow iron sausage and, with no steam power, operated entirely by hand. Her depth (about 6 feet) was controlled by flooding or pumping out ballast tanks and by releasing lead wights bolted to the keel. One theory posits that the pressure wave from the torpedo explosion knocked senseless or killed the crew, allowing even small leaks to sink her and drown them.

In his open launch on the surface, Lieutenant Cushing’s only defense against Albemarle was surprise, which in the dark, he managed to achieve just long enough to position the torpedo before the ironclad opened fire and the torpedo exploded. Blown overboard, he and one other crewman escaped, two drowned, and eleven were captured.

Spuyten Duyvil was neither submerged nor on the surface. She was larger, much more solidly built and protected like a small monitor. With her slanted deck at the waterline, enemy rounds were most likely to glance off. She had more reserve buoyancy than Hunley along with steam pumps. Assuming it functioned as designed, the torpedo deployment machinery was more efficient than fixed or hand-operated spars of other boats.

For centuries, naval weapons had been simple iron tubes in carriages on wheels or slides firing iron balls. This entire vessel was an innovative, complex, mechanical delivery system at the height of the industrial revolution. Spuyten Duyvil would have had good odds against Rebel ironclads, and she represented the seeds of future submarines.

Post war, this torpedo boat was employed destroying Confederate obstructions and torpedoes on the James River, clearing the way for President Lincoln’s visit to Richmond, and then served as a platform for experiments in New York until 1880.

[1] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 29 vols. (Washington, DC, 1894-1921), Series 1, vol. 11, 644.

[2] Frank M. Bennett, The Steam Navy of the United States: A History of the Growth of the Steam Vessel of War in the U.S. Navy, and of the Naval Engineer Corps (Pittsburgh, PA, 1896), 482.

[3] Wm. W. W. Wood and John L. Lay, “Improved Apparatus for Operating Submarine Shells or Torpedoes, Specification forming part of Letters Patent No. 46853, dated March 14, 1865.”

[4] “Text from the English magazine ‘Engineering’, 26 October 1866, page 322: The ‘Spuyten Duyvil,’” Naval Historical Center (https://web.archive.org/web/20051129072610/http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/images/h95000/h95112l.htm), accessed December 23, 2022.

[5] Bennett, Steam Navy of the United States, 482.

Pray for peace ??

Spuyten Duyvil Creek in NY was also the site of Johnson Ironworks, which built many cannons during the war, including the guns for the USS Monitor. I’ve also heard it translated as “In spite of the devil” and “spiteful devil.”

Didn’t know that. Great information. Thank you!

As an old retired naval engineer, always glad to see what the engineers/constructors had achieved in their day.