Francis Flanagan’s Fredericksburg Redemption

ECW welcomes back guest author Dan Masters

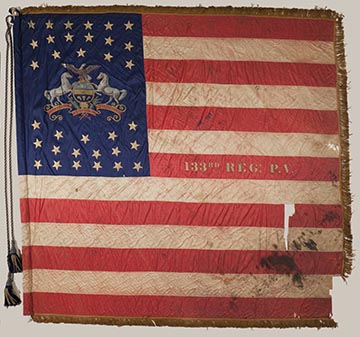

For the first four months of his service, Second Lieutenant Francis M. Flanagan of the 133rd Pennsylvania was a pariah in his company. It wasn’t due to any personal reasons, though. The young lieutenant didn’t understand the manual of arms and was unable to instruct his men in their duties; to be sure, the men felt he was simply incompetent and unfit to lead them into battle.

The trouble developed soon after the 24-year-old Cambria County native was commissioned a second lieutenant of Co. F, also called the Mountain Guards, on August 15, 1862. It quickly became evident to the men that despite Lieutenant Flanagan’s zeal and gentlemanly manners, he was incapable of drilling them and knew nothing of military matters. Within a week, Flanagan received a petition signed by 59 members of the company requesting that he resign his commission and go home. “We are all desirous to place a person who will be capable to instruct us in the manual of arms,” the petition stated. “We do not, by any means, bear any disrespectful feeling towards you, because we are compelled to request you to resign. Knowing your incapability to discharge the duties required of you, we are thus forced to do so.”

Flanagan flatly refused the request but, nothing daunted, the men appealed to their regimental commander Colonel Franklin B. Speakman for redress of their grievances. “We ask you to remove the aforesaid lieutenant so as to enable us to fill the vacancy. We have a private in our company who we are anxious to place over us. He is thoroughly acquainted with the present drill and is a first-class drillmaster and if only elected lieutenant, he will have the company perfect in the manual of arms,” the petition argued. Perhaps appreciating the sentiment but deploring the method, Colonel Speakman declined the request.

On August 26th, the exasperated members of Co. F addressed an appeal to Pennsylvania’s wartime governor, Andrew G. Curtin, asking him to remove Flanagan. This would allow the company to elect Richard M. Jones who had previously served as a lieutenant in the Scott Legion [20th Pennsylvania] and was a superb drillmaster. “We are anxious to place him over us, knowing that such an object must be accomplished before we shall be fit to go into active duty,” they said. “We now close, imploring you to interfere on our behalf and ask your pardon for thus intruding upon you.”

By this point, the 133rd Pennsylvania had arrived in camp at Arlington Heights, Virginia, and soon was assigned to 5th Army Corps division of General Andrew A. Humphreys and actively engaged in repelling the Confederate invasion of Maryland. The Pennsylvanians just missed out on Antietam, arriving on the field the day after the battle. For the next two months, the regiment spent much time engaged in company and battalion drill while marching with the army into northern Virginia. All the while Governor Curtin worked behind the scenes to get the War Department to act on the petition to dismiss Lieutenant Flanagan from the service. As one of the petitioners later explained, “a couple weeks prior to the Battle of Fredericksburg, an examining committee declared him incompetent to hold a commission.” But the wheels of military justice ground slowly and while Flanagan and Co. F awaited the final word from the War Department, events soon would occur that would turn the decision of the examining commission on its ear.

The Army of the Potomac crossed the Rappahannock River on December 11, 1862, and two days later the 133rd faced their first test of combat by participating in one of the last charges on Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg. “Knapsacks were unslung bayonets fixed, and orders received to charge the works on Marye’s Heights,” Colonel Speakman reported. “We charged up and over a hill about 250 yards when we came upon a line of troops lying down. My men, not knowing that they were to pass over this line, covered themselves as well as they could in the rear of this line. The troops in front, neither advancing or retreating, and a second charge being ordered, I passed over the prostrate troops and charged to the right of and past the brick house and within 50 yards of the stone wall and to the left of the house to the crest of the hill. This position was held for an hour under a most terrific fire from the enemy’s infantry and artillery.”

The 133rd suffered heavily and matters in Co. F appeared particularly grim. The Pennsylvanians went into action with Captain John M. Jones’s injunction of “be firm as steel boys” ringing in their ears, and the regiment’s fortitude was sorely tested in front of that stone wall. The 25-year-old captain had returned to the regiment just two days before, not yet recovered from a bout of typhoid fever but determined to lead his men into their first fight. First Lieutenant William A. Scott was among the first hit, bullets passing through both his head and his heart, killing him instantly. Then Captain Jones took a nasty wound in the thigh. “Captain Bobb said, ‘Captain Jones, you are wounded. Leave the field.” The captain answered, “Yes, I am wounded, but don’t tell my men,” Lieutenant Flanagan later recalled. “With these words he lay down on the ground and just at that moment he was struck on the top of the head and ball passed down into his body. About the same time he was struck with a shell in the arm. He lived some time but was insensible to anything around him.” Jones would be hauled off the field to the divisional hospital where he soon died.

This left Lieutenant Flanagan in command of the company and, much to everyone’s surprise, he proved a lion in battle, one local editor proclaiming that Flanagan performed “prodigies of valor and has endeared himself to his command with an undying love.” Amid the bombshells and the blood, the young lieutenant who couldn’t drill his men showed that he could do something infinitely more valuable: he inspired and led them through the holocaust of battle. “He acted so bravely and gallantly that a reaction took place in the minds of his opponents,” Private Ellis R. Williams recalled. “The entire company, without any exception, absolutely adore him for the energy and pluck he then and there exhibited. The men entertain high hopes that he may be promoted to our captain.” Interestingly enough, Williams was the first man to sign the petition to have Flanagan dismissed back in August and now he became one of the lieutenant’s strongest supporters.

Within days, the 133rd Pennsylvania was back at camp near Falmouth, Virginia. Fredericksburg proved a bloody disaster for Co. F: out of 54 men who went into action, 8 were killed, 17 wounded, and 3 more were listed as missing, more than 50% of the company. The Pennsylvanians barely had time to deal with this personal tragedy when the hammer from the War Department struck: an order came down discharging Lieutenant Flanagan from the service effective January 10, 1863. The men howled at the injustice, but realizing that they had only themselves to blame, quickly drew up a petition with Lieutenant Colonel William McCartney’s assistance “begging for his reinstatement. The petition was signed by every member of Co. F while Colonel Peter Allabach, commanding the brigade, wrote a letter to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton recommending his reappointment,” Williams continued.

But until that petition worked its way up and down the chain of command, Lieutenant Flanagan was out of a job and sadly packed his bags and returned to his hometown of Ebensburg, Pennsylvania. Ellis Williams, perhaps out of protest to the injustice of the act or guilt at what he had set in motion, chose to accompany the lieutenant home and deserted the army. Once the two men arrived back in Ebensburg, they stopped into the local newspaper office and passed along the tale that Flanagan was home on a brief furlough while Williams had been discharged. The story didn’t hold water for long as a week later, Williams came clean in a communication to the Alleghanian newspaper that gave the whole sad tale, and closed with the statement that Flanagan “has been dismissed from the service, but now he stands higher in the estimation of his men than he ever did before. That he will be reinstated and promoted to a higher position in his company I have not the least doubt.”

In mid-February, the members of Co. F gathered to elect new officers and Lieutenant Flanagan was elected captain without opposition. It took the War Department until the end of March to work their way clear through this tangled tale, and on March 25, 1863, Francis M. Flanagan again entered the service of the United States, now with the rank of captain. The Alleghanian proudly passed along the news stating that “Co. F has won an enviable name and fame for heroism and endurance and under the leadership of Captain Flanagan, its future history will decorate as bright a page as its past. We congratulate all hands on the happy result of the issue.”

The future for Captain Flanagan and the 133rd Pennsylvania was destined to be short-lived; by the time of the Battle of Chancellorsville in May, the regiment was approaching the end of its nine-month enlistment. After seeing action on May 3 near the Chancellor House where the regiment lost Adjutant Edward C. Bendere and nine men wounded, the 133rd Pennsylvania withdrew and returned to camp in Falmouth where it departed for Harrisburg, Pennsylvania on May 19, mustering out of service a week later. Captain Flanagan mustered out at the head of his company and lived to the age of 73, passing away February 17, 1912, in Coalport, Pennsylvania where he is buried at Saint Basil the Great Roman Catholic Cemetery.

Sources:

Bates, Samuel P. History of the Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5. Harrisburg: B. Singerly, 1869, pgs. 263-265, 274-275

Petitions of Co. F, 133rd Pennsylvania Volunteers, Record Group 19, 14-4035 Carton 81, Pennsylvania State Archives

Letter from Private Ellis R. Williams, Co. F, 133rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, The Alleghanian (Pennsylvania), January 22, 1863, pg. 3

Letter from Second Lieutenant Francis M. Flanagan, Co. F, 133rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, The Alleghanian (Pennsylvania), December 25, 1862, pg. 3

“On the Rappahannock,” The Alleghanian (Pennsylvania), December 25, 1862, pg. 2

“Be Firm as Steel, Boys!” The Alleghanian (Pennsylvania), January 22, 1863, pg. 3

“In Town,” The Alleghanian (Pennsylvania), January 29, 1863, pg. 3

“The Case of Lieut. F.M. Flanagan,” The Alleghanian (Pennsylvania), February 5, 1863, pg. 3

“Lieut. F.M. Flanagan,” The Alleghanian (Pennsylvania), February 26, 1863, pg. 3

Find-A-Grave entry from Francis M. Flanagan (1838-1912)

This seems like it would be excellent source material for a novel or screenplay. Wow! Did Private Williams end up rejoining the company as well?

Yes, Private Williams returned by early March and resumed his correspondence with the local newspaper keeping them apprised on conditions within the company.

thanks Dan, great story … only in an army of citizen soldiers would this happen.