Grant’s Last Naval Battle: Trent’s Reach on the James River, Part 2

Part 2 of 2: Part 1 related the buildup to the battle as Confederate ironclads of the James River Squadron, under the command of Flag Officer John K. Mitchell and accompanied by wooden gunboats and torpedo boats, descended the stream to threaten the massive Union supply base at City Point, Virginia.

On the evening of January 23, 1865, a telegram arrived at General Grant’s headquarters notifying him that the enemy was coming. He dispatched Lieutenant Colonel Horace Porter and two other staff officers by steam tugs with requests for navy gunboats anchored nearby to “move up and make a determined effort to prevent the enemy’s fleet from reaching City Point.” The general then retired with Mrs. Grant leaving instructions to rouse him instantly with news.

“The night was pitch-dark,” as they visited each boat, Porter wrote. “Their commanders . . . displayed that cordial spirit of cooperation always manifested by our sister service, expressed an eagerness to obey General Grant’s orders as implicitly as if he had been their admiral. Most of these vessels were out of repair and almost unserviceable, but their officers were determined to make the best fight they could.” Even the army’s commanding general could not issue direct orders to a navy officer without authorization from navy command.[1]

Sometime after 11:00, the Rebel squadron arrived in Trent’s Reach. The ironclads CSS Virginia and CSS Richmond threw out stern anchors half a mile above Union river barriers of sunken vessels, pilings, booms, and torpedoes. The ironclad CSS Fredericksburg, with wooden gunboat Hampton and torpedo boat Hornet alongside, approached the obstructions and hovered. Flag Officer Mitchell ordered Lieutenant Charles W. Read to man a boat, inspect the barricade, and sound water depth. “The enemy opened upon us with musketry and a small mortar,” reported Read, but they found a gap with no less than 2 ½ fathoms (15 feet) depth, just sufficient for the ironclads.[2]

Fredericksburg surged through the barrier sideswiping a hulk and shearing off her torpedo-defenses outriggers. The hull shuddered as timber pieces surfaced alongside; she apparently struck sunken wreckage, which started a troublesome leak. Union batteries threw at her—according to artillery commander Colonel Henry L. Abbot—some 40 10-inch mortar rounds along with “musketry fire from all the spare artillerymen.” It was now 1:00 a.m. Notice of the breach roused the General and wife from their bed.[3]

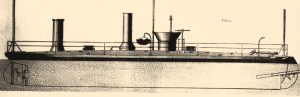

The only major Federal warship available, the double-turreted monitor USS Onondaga, had been anchored out of range of Rebel guns below Trent’s Reach with the squadron commander, Commander William A. Parker, aboard. Nearby were the sidewheel gunboat USS Massasoit, two torpedo boats, and two armed tugs. The commander’s few other warcraft were scattered downstream and at City Point including two converted New York ferries, a converted screw merchant steamer, two new sidewheel gunboats, and another tug.

Parker had standing orders from Admiral David D. Porter that torpedo boats must be ready in Trent’s Reach with their spars armed for instant service at night: “If an ironclad should come down they must destroy her, even if they are all sunk.” On the morning of January 23, Parker stationed the torpedo boats between his monitor and the obstructions. That evening, they heard heavy firing to the north followed after midnight by flashes and detonations up the reach. Signals from the watch tower informed them that boats were descending. A tug reported a Rebel vessel downstream of the obstructions.[4]

Onondaga’s logbook recorded: “At 3 hove up anchor and dropped down below the pontoon bridge in charge of pilot.” Massasoit remained with the torpedo boats, but in the dark, they would never find the enemy. (See previous post for the fascinating story of the torpedo boat USS Spuyten Duyvil.) Parker later justified this retrograde movement: “I thought there would be more room to maneuver the vessel, and to avoid the batteries bearing on Dutch Gap.”[5] An angry Admiral Porter would court martial him afterwards, but Navy Secretary Welles vacated the verdict calling it an error of judgment.

With Flag Officer Mitchell aboard, Fredericksburg cleared the barrier and anchored a mile and a half downriver under “an annoying mortar fire.” Mitchell ordered a light placed on the obstructions to guide the remaining squadron through and started back up by boat to Virginia still above the obstructions. She had gunboat Nansemond, tug Torpedo, and torpedo boat Scorpion secured alongside. “To my inexpressible mortification I found her aground.”[6]

Richmond also was grounded nearby with gunboats Drewry and Beaufort and torpedo boat Wasp. Unobserved by their pilots in the black night, powerful river currents had dragged the ironclads and their anchors into the shallows. “Every exertion to get her off proved unsuccessful,” reported Richmond’s Commander Kell, “and the enemy’s batteries pouring in a heavy fire upon us of shell and shot, besides their mortar batteries throwing with great precision.” Confusion reigned illuminated by exploding shells.[7]

The tide had been ebbing for hours; the ironclads could not be refloated before morning high water. Mitchell directed his wooden boats to take shelter behind a point of land under the guns of Battery Dantzler. He recalled Fredericksburg from below the barricades, ordering her to anchor above the stuck sisters and cover them with her broadside. Colonel Abbot’s batteries discharged almost 50 hundred-pounder and 24 ten-inch mortar rounds but, he wrote, “the darkness prevented the effect of this fire from being known.”[8]

At Union headquarters, Col. Porter recalled, “In about two hours it was reported that only one of the enemy’s boats was below the obstructions, and the rest were above, apparently aground.” More guns had been deployed; more dispatches written. Grant instructed Gibbon’s XXIV Corps to stand ready for a possible attack on their front. Frustrated with Commander Parker’s lack of aggressiveness, he directed gunboat captains still at City Point to proceed immediately above the pontoon bridge. “This order is imperative, the orders of any naval commanders to the contrary notwithstanding. By authority of the Secretary of the Navy.”[9]

The general telegraphed Parker to send all assets immediately to the front, “or, at least, above the large amount of public stores accumulated for the subsistence of the army and navy. . . . It would be better to obstruct the channel of the river with sunken gunboats than that a rebel ram should reach City Point.” The commander’s duty was “to attack with all the vessels,” using them as rams as well as batteries even if losing half. Headquarters finally quieted down, noted Col. Porter, so “the general-in-chief and Mrs. Grant retired to finish their interrupted sleep.”[10]

Flag Officer Mitchell’s battle report: “As anticipated, at daylight the enemy’s batteries and sharpshooters on the south side of Trent’s Reach, that had been firing upon the squadron without effect . . . were now enabled to take deliberate aim.” Their fire—from 800 to 1,500 yards range—concentrated on Richmond and the gunboat Drewry, grounded close together in line. The immobilized ironclads could not direct a gun on enemy batteries.

“At 7:10 a.m.,” continued Mitchell, “a shell exploded the magazine of the Drewry, blowing her to pieces and covering the deck of the Richmond with the fragments.” Drewry’s men had just abandoned her, but the blast killed two as they scrambled aboard Scorpion. That damaged boat would drift down into enemy hands. “The shock felt on board the Richmond was terrific,” wrote Commander Kell. “I ordered the crew to keep silence and remain at their quarters, which was observed with prompt obedience.” He couldn’t count the number of rapid hits; three heavy shot caused “decided shocks,” knocked off bolt heads, and indented the iron shield.[11]

Union guns shifted to Virginia. About 10:30 a.m., Onondaga returned with the USS Hunchback, a converted ferry, and opened fire at 1,600 yards. Virginia was struck some 70 times, reported Mitchell, mostly 100-pounder rifle shells from shore. Onondaga delivered a 150-pound shell and a XV-inch solid shot that blew a 2-foot hole in the iron shielding and wood backing, killing one and wounding two. A Rodman rifle shell penetrated an open port and exploded against the gun wounding a lieutenant and 7 men.

Virginia’s casemate suffered structural damage with multiple bolts and armor plates dislodged, but the battery remained mostly intact. “The smokestack was so badly cut up and the exhaust pipe cut in two as to allow the steam to escape on the spar and gun decks, but it did not prevent the raising of steam.” By noon, Virginia and Richmond finally refloated, retreated around the point of land, and anchored with the rest. Despite losses and damage, concluded Mitchell, “preparations and dispositions were at once made to move down the river as early in the night as the tide would serve.”[12]

Colonel Abbot counted 196 rounds of solid and case shot, percussion and timed shell fired at the rams with 68 hits, but at the oblique angle, most glanced off, dislodging a few iron plates. Enemy batteries across the water shot back, dismounting his guns, blasting chunks out of the revetment, knocking men down, killing three. He fired another 300 shots at them. His guns, along with the difficulties of navigation, wrote Abbot, “saved this army from a serious disaster.”[13]

Flag Officer Mitchell brought his squadron back down to Trent’s Reach that night. “Soon after dark the enemy exhibited a brilliant Drummond light [limelight],” he reported, which enabled Union batteries to aim “almost as well at night as by day.” That light, along with escaping steam blowing through gaping holes in the smokestack and steam exhaust line into the gundeck, blinded the pilots. Under intense bombardment and unable to navigate, Mitchell felt compelled to again retreat.[14]

“This was the last service performed by the enemy’s fleet in the James River,” concluded Col. Porter. All vessels were blown up or scuttled during the evacuation of Richmond on April 2. Trent’s Reach also was General Grant’s last naval battle.[15]

Sources:

[1] Horace Porter, Campaigning with Grant (Annotated) (Big Byte Books, 2016) Kindle Edition, 297.

[2] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 29 vols. (Washington, DC, 1894-1921), Series 1, vol. 11, 683. Hereafter cited as ORN. All references are to Series 1, Vol. 11.

[3] Ibid., 659.

[4] Ibid., 662.

[5] Ibid., 656.

[6] Ibid., 677, 669.

[7] Ibid., 673.

[8] Ibid., 659.

[9] Porter, Campaigning with Grant, 299; ORN, 635.

[10] Porter, Campaigning with Grant, 299.

[11] ORN, 699-70, 673-4.

[12] Ibid., 670.

[13] Ibid., 660.

[14] Ibid., 671-3.

[15] Porter, Campaigning with Grant, 299.

Interesting and well-written. Thank you for the story.

Good one. Thanks

Thanks Capt. Onondaga was a hybrid design with features from both the “Bureau design” and Ericsson’s design. It isn’t clear if this resulted in a compromise that made the ship limited in effectiveness. But I guess if you consider the Passaics a pure-design alternative maybe not all that different in the end.

Thank you for such a great story! Pardon my ignorance, though, but how does a ship pass above or below a pontoon bridge? Do they have to dismantle part of the bridge for the ship to pass through? ? I don’t get it.

Thank you for such a great story! Pardon my ignorance, though, but how does a ship pass above or below a pontoon bridge? Do they have to dismantle part of the bridge for the ship to pass through? ? I don’t get it.

Hi Debra. Thanks for the question. The army was adept at building and dismantling the bridges and would have been ready to open sections as needed for ships to pass.

Thank you! To me, it just seemed too cumbersome, but it nakes sense now.

When was the USS Merrimack officially renamed the CSS Virginia?

Eric: The CSS Virginia was officially commissioned on February 17, 1862. Sorry I missed your question earlier.