Ambrose Burnside Weathers the Gale

The thin barrier islands of North Carolina’s Outer Banks bulge eastward into the Atlantic Gulf Stream coming to a point at Cape Hatteras and Diamond Shoals, creating a vortex of powerful currents, hurricanes, Nor’easters, and other ocean-driven storms. More than 5,000 ships have gone down in these waters since 1526 including Queen Anne’s Revenge (1718), flagship of Blackbeard the pirate. Such tempests still scour the ocean sands revealing the ruins of old wrecks. Weather in this “Graveyard of the Atlantic” formed a formidable obstacle for Civil War navies.

A fierce gale along that coast in late October 1861 scattered the 77-ship invasion force heading for Port Royal Sound, South Carolina, sinking or driving ashore three food and ammunition ships and a transport carrying 300 Marines; all but seven sailors and Marines were rescued. Admiral David D. Porter’s massive fleet encountered similar hazards on the way to Fort Fisher, December 1864. The USS Monitor was lost in a gale off Cape Hatteras, December 1862. Some blockade runners are down there too.

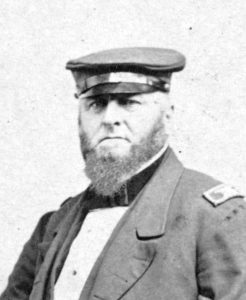

Also in the winter of 1862, a series of near catastrophic weather events almost cancelled Brigadier General Ambrose Burnside’s amphibious expedition to capture the strategically vital North Carolina Sounds—the first major joint victory of the conflict. Chatting with his good friend Major General George McClellan one evening the previous fall, Burnside proposed to form a “coast division” of 12,000 to 15,000 men, mainly from seaboard states, many with experience in coasting and mechanical trades. He would fit out a fleet of shallow-draft vessels to transport the division, its armament, and supplies.

This force, noted Burnside, “could be rapidly thrown from point to point on the coast,” landing troops, capturing strategic targets, raiding the interior, disrupting enemy transportation and communications, and dominating inland waterways. The U.S. Navy would be called upon to supervise and protect transports, eliminate Confederate naval interference, suppress shore batteries and fortifications, and cover landings.[1]

Secretary of the Army Stanton approved McClellan’s plan for the “Burnside Expedition” to enter the sounds at Hatteras Inlet, capture and occupy strategic points from Roanoke Island north to the Dismal Swamp Canal and south to New Bern, Fort Macon, and Beaufort.

He would interdict the north-south railroad feeding supplies from Wilmington to Petersburg and Richmond— “the lifeline of the Confederacy”—and might even threaten the state capital at Raleigh. This was a dagger into the heart of the Confederacy.

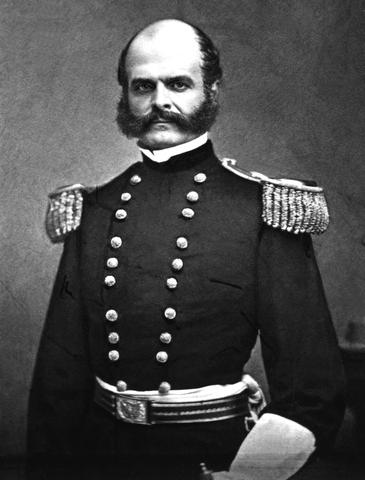

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles supported the plan as an adjunct to the blockade. He tasked the commander of the Atlantic Blockading Squadron, Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough, to support Burnside. President Lincoln held unrealistic hopes that hordes of coastal North Carolinians would rally to the flag, perhaps providing his first opportunity to establish a loyal state government in Rebel territory.

With no precedent, procedures, or experience in massive joint operations, Burnside developed an excellent partnership with Flag Officer Goldsborough. Together they integrated naval units and merchant vessels under Goldsborough’s command into the command structure, creating the first dedicated, rapid-deployment, amphibious force.

But procuring shallow draft vessels was much more difficult that winter of 1861, “almost everything of that sort having already been called into service” for the blockade.

The general and the flag officer assembled a “motley fleet” of gunboats, river and coastal steamers, ferries, tugs, and barges to transport 15,000 troops with arms, baggage, camp-equipage, rations, etc. Decks were reinforced to support from 4 to 6 naval guns with sandbags or haybales stacked around for protection.

“After most mortifying and vexatious delays,” wrote Burnside, troop transports assembled in Annapolis harbor to embark troops. Another fleet of light-draft sailing vessels gathered in Baltimore to load building material for bridges, rafts, and scows, along with supplies including trenching tools, quartermasters’ stores, and ordnance stores. The over eighty vessels rendezvoused at Fort Monroe.

However, noted the general, “Much discouragement was expressed by nautical men and by men high in military authority as to the success of the expedition.” President Lincoln and General McClellan were repeatedly warned that the fleet was unfit for sea and the excursion would be a total failure. Nevertheless, the Burnside Expedition departed Hampton Roads on January 11, 1862.

Stung by severe criticism and determined to demonstrate his faith in the fleet, Burnside embarked with a few staff officers on its smallest ship, the steamer Picket, eschewing his official headquarters on the large and comfortable passenger steamer George Peabody.

His vessels had their weaknesses, wrote the general, but were the best that could be procured. “It was necessary that the service should be performed even at the risk of losing life by shipwreck.”

On rounding Gape Hatteras, they met a gale, and little Picket got into the trough of the sea. “It seemed for a time as if she would surely be swamped…. We passed a most uncomfortable night,” recalled Burnside.

Everything on the deck not lashed down was swept overboard. Men, furniture, and crockery below decks were thrown about. “At times, it seemed as if the waves, which appeared to us mountain high, would ingulf us, but then the little vessel would ride them and stagger forward in her course.”

Just before noon of January 13, the bedraggled fleet reassembled off Hatteras Inlet. A tug came out to pilot them through the breakers and over the bar. Picket led the way, bravely cresting the breakers until she was safely anchored inside the harbor. Vessel after vessel followed her in, crowding the anchorage.

One steamer grounded on the bar laden with supplies and ordnance stores, a total loss. Her officers and crew clung in the rigging until rescued by surfboats the next day. A troop vessel also grounded, but gallant volunteers with a tugboat pulled her off the bar into the harbor. The ship Pocahontas went down with over a hundred horses. A gunboat sank in the inlet but with no lives lost. Water and coal vessels did not even approach the inlet, remaining safely at sea. Two officers drowned when their boat swamped in the breakers, the only losses during the voyage.

Two weeks of terrible winds and raging waters followed. Vessels dragged their anchors, grounded on the beach or the bar, and collided with each other causing significant damage. Crammed afloat, unable to disembark, thousands of lonely, seasick men consumed dwindling food and fresh water with no resupply possible. Supply vessels were still outside the harbor.

“At times it seemed as if nothing could prevent general disaster,” wrote Burnside. “On one of these dreary days I for a time gave up all hope, and walked to the bow of the vessel that I might be alone.” Soon after, however, a “most copious fall of rain came to our relief.” Sails were spread to catch the water, casks filled, and thirst slaked throughout the fleet. Burnside cheered up, but he was “very much ashamed” of his moment of weakness.

To advance from Hatteras Inlet into Pamlico Sound proper, the fleet had to cross another area of shoal water called “the swash.” Burnside had been informed that the swash was covered with eight feet of water, but to his dismay discovered it was only six feet deep, too shallow for most of his vessels. He had to deepen the channel.

So, enterprising Yankee captains ran their ships under full steam up onto the shallow, sandy bottom. To secure the ships in place, they lowered anchors into boats, rowed ahead, and dropped them (a process called “kedging”). As the tide retreated, swift running currents washed sand from under the beached hulls, floating the vessels. They forged ahead again repeating the process until a channel was gouged allowing the fleet to pass.

Burnside and Goldsborough proceeded to execute a textbook amphibious assault of Roanoke Island without any textbook, conquered the northern reaches of Albemarle Sound, and then proceeded to the southern end of Pamlico Sound where another weather event intervened. The target was New Bern, a key port on the Neuse River.

On the 12th of March, the entire command anchored off the mouth of Slocum’s Creek, fourteen miles from the city. The approaches had been obstructed by pilings and sunken vessels, which had to be removed with explosives. The troops were put ashore the next morning in much the same way as at Roanoke and by 1 o’clock debarkation was completed with the brigades in line of march.

Then drenching rain began, making roads almost impassable. The men had only what ammunition they could carry. No artillery could be brought forward except small howitzers hauled by dragropes. “This was one of the most disagreeable and difficult marches that I witnessed during the war,” recalled Burnside, presumably comparable to his disastrous “mud march” at Fredericksburg in January 1863 except that it would be successful. We could call this one the “sand march.” They encountered enemy pickets just before dark and entered “a most dreary bivouac.”

Early the next morning, notwithstanding the fog, the attack commenced, advancing against stiff resistance to a large fort a few miles from the city. Navy gunboats worked their way upriver flanking the advance, providing artillery support. In a sharp but brief contest on the afternoon of March 14, blue lines took the works as Confederates fled, burning the bridge behind them. Fort Macon and Beaufort soon capitulated leaving the Union in charge of the sounds and coasts of North Carolina for the remainder of the war.

“The results of this important victory were great, particularly in inspiring the confidence of the country in the efficiency of its armies in the field,” recalled the general. Burnside longed to capture more Rebel territory, perhaps even Raleigh and Wilmington, but much to his sorrow, he and most troops were withdrawn to the Peninsula on July 3 to reinforce McClellan’s flailing operations on the Peninsula.

The often-maligned General Ambrose Burnside and his navy counterpart, Flag Officer Louis Goldsborough, deserve credit for success in this singular campaign despite the enemy and the weather.

Sources:

[1] All Burnside quotes: Ambrose E. Burnside, “The Burnside Expedition,” in Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, ed., Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, 4 vols. (New York, 1884-1888), 1:661-663.

The weather caused more problems to Burnside than the Confederates.

Burnside did quite well in the minor leagues of coastal North Carolina against an array of politicians-turned-generals. He would be found wanting when called up to the major leagues in Northern Virginia against professional opposition.

Regardless of who his opponents were, he had significant accomplishments in executing a combined operation in cooperation with the USN. including – as this article points out – overcoming a major obstacle presented by the weather in a location that already presented major challenges. Among other things, he also capably staged expeditious training of the landing force.

HOLY S—!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

An excellent post, Dwight!

This is a great post Dwight!

With all of Burnsides’ many failures at Fredericksburg, the Mud March, Spottsylvania, etc,., it is good to read of his success in North Carolina, despite formidable obstacles.