Discovering Family Connections to the Centralia Massacre

ECW welcomes guest author Tonya McQuade

Centralia is a small Missouri town of 4,200 people that straddles Boone and Audrain County, about 130 miles northwest of St. Louis. It is also the town where my great-great grandparents, Francis “Frank” Marion Traughber and Mariah “Marnie” Agnes Bryson Traughber, lived the latter part of their lives. They are buried in Centralia Cemetery, alongside several other family members.

(Photo Credit: Wikipedia Commons)

On September 27, 1864, this small town became the site of the brutal Centralia Massacre, and later that same day, the site of one of the bloodiest Civil War battles in terms of the percentage of soldiers killed. Two branches of my family, as it turns out, had connections to this massacre – but they were supporting different sides in the war.

I first learned of a connection while searching for information about Francis Marion Traughber – his name appeared in the 2008 academic study titled “This Work of Fiends”: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives on the Confederate Guerrilla Actions at Centralia, Missouri, September 27, 1864, by Thomas D. Thiessen, Douglas D. Scott, and Steven J. Dasovich. According to the text, F.M. Traughber received a telegram from a George Washington Bryson asking Traughber to tell Bryson’s sons he had been injured by an old bullet that had never been removed from his pelvis. The original bullet wound resulted from being shot in 1864 by Union troops who were pursuing him – the same Union troops that would later be killed in the Battle of Centralia. [1]

As explained in the text: “The minie ball [with which Bryson was shot] was not extracted from the hip and came near causing the death of Captain Bryson some forty years after the war. He was riding a horse on his ranch in Texas after cattle, when the horse jumped, throwing Mr. Bryson upon the saddle tree and the leaden ball fractured the bone in his hip. He was taken to a hospital for treatment, and it was F.M. Traughber of Centralia who carried the news to the Bryson boys in this section, Capt. Bryson having directed the telegram to Mr. Traughber here.” [2]

Why would he send this telegram to F.M. Traughber?

G.W. “Wash” Bryson was Marnie Bryson Traughber’s brother. During the war, however, Bryson was also a Confederate captain, serving from 1861-1865 in Col. Caleb Perkins’ Battalion, Missouri Infantry, Company C. In Fall 1864, he was on a recruiting mission in his former home county and looking for opportunities to participate in bushwhacking attacks against Union soldiers, supporters, and supplies. Such attacks were “committed by men recruited by authority of Sterling Price, as attested by his son, Edwin M. Price, who visited the rebel camps and saw the documents from his father, authorizing the formation of guerrilla gangs by Perkins and [Clifton] Holtzclaw.” [3]

About three weeks before the Centralia Massacre, on September 7, 1864, Bryson and his new recruits fired on Federal troops who were “guarding a wagon load of ammunition and guns, being taken from Centralia to Columbia … and though [Union] Major Evans in charge of the troops had a full company, they ran, abandoning their charge,” and Bryson was able to capture 75 guns and 10,000 rounds of ammunition. [4] Soon after this, he stopped a train near Centralia that was carrying four carloads of horses. He and his men stole 40 horses, as well as other supplies from the train, plus captured Federal troops whom Bryson threatened to kill, but eventually released about a week later. [5]

The federal troops in the Centralia Massacre were not so fortunate.

Around 9 a.m. on September 27, guerrilla leader William “Bloody Bill” Anderson and about 80 of his bushwhackers rode into Centralia. Initially, the group seemed more interested in looting local businesses, drinking large amounts of whiskey, and robbing a stagecoach. However, when they heard the North Missouri Railroad train coming from the direction of Mexico, Missouri, they hurried toward the depot. [6]

There, they blocked the rail line, swarmed the train, and separated the civilians from the soldiers. They threatened and robbed the civilians, then ordered the twenty-three Union soldiers onboard to strip off their uniforms. The soldiers, from the 1st Iowa Cavalry, were mostly unarmed as they were heading home on furlough after Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign. [7]

The guerrillas also asked if any officers were present. Sergeant Thomas Goodman bravely stepped forward, thinking that by doing so, he might save the others. Instead, Anderson and his men then shot the other twenty-two soldiers, scalping and mutilating some of them before setting fire to the train and sending it down the track toward Sturgeon to the west. They then torched the depot and rode off, taking Goodman with them as a prisoner. The burning train came to a stop a few miles outside of town at the farm of James R. Bryson – Marnie’s oldest brother. [8]

Goodman, who ten days later escaped his captivity, described the Centralia executions and scalpings as the “most monstrous and inhuman atrocities ever perpetuated by beings wearing the form of man.” [9]

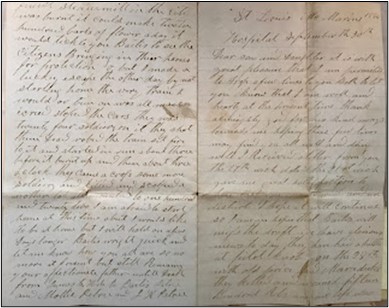

In a Civil War letter written by my 3rd great-grandfather, James Calaway Hale of Savannah, Andrew County, Missouri, who served in the 33rd Missouri Infantry, I discovered a third family connection: he narrowly avoided being on the train that was attacked in the massacre because he did not get the furlough he had requested. In his letter, he writes both of the “glorious news” of the Union victory at Pilot Knob and the “lucky escape” he made by not being on the North Missouri train on September 27:

St. Louis, the Marine Hospital, September 30, 1864

Dear son and daughter,

… We have glorious news today. They have had a battle at Pilot Knob on the 28th with old Price and Marmaduke. They killed and wounded 1500 Rebs, and our loss was nine killed and sixty wounded. That is the way I love to hear. It will not take long to clean old [Confederate Gen. Sterling] Price and [Brig. Gen. John S.] Marmaduke up at them licks. They is great excitement here at this time. They have been drafting and arming all the militia in the county. They is this morning twelve thousand militia in camp here in Camp Jackson in sight of Benton Barracks [in St. Louis, Missouri], and three thousand more will be there soon. Several thousand cavalry have passed through here two or three days ago for to meet Old Price. I think they will get Old Price, but they say Old Price is making for Rolla [Missouri]. They is not scarcely a man left – business is all stopped through the city….

O, but I made a lucky escape the other day by not starting home. The very train I would have been on was all massacred – stopped the [railroad] cars. They was twenty-four soldiers on it. They shot them dead, robbed the train, set fire to it, and started it running down the track before it burnt up. About three o’clock they came across some more soldiers and killed and scalped another lot. All amounted to one hundred and twenty-two. I am afraid to start home at this time. I would like to be at home, but I will hold on a few days longer….

(Photograph by Tonya McQuade, April 2022)

Confederate Major General Sterling Price had encouraged guerrilla attacks and railroad disruptions to aid his advance on northern Missouri with his Army of Missouri. He was determined to help the Confederacy retake Missouri now that so many Union soldiers had been sent east – and he had his sights set on Jefferson City or possibly even St. Louis.

Price had also ordered Bryson to scout for men in Boone County to join the Confederate army. Called “Little Dixie” because of its strong southern support, Boone County, along with the surrounding region, was home to many anti-Unionists, including some who had moved there after Union General Thomas Ewing, Jr.’s General Order No. 11 forced them from their homes the previous year. Ewing’s controversial order, issued following the guerrilla attack led by Anderson and guerrilla leader William Quantrill on Lawrence, Kansas, in August 1863, required that almost all persons living in Jackson, Cass, Bates, and Vernon counties along the Missouri-Kansas border leave their homes immediately as part of a Union effort to clear out any guerrilla support.

When Bryson’s men encountered Anderson’s guerrillas, they mistakenly fired upon them, thinking they were the enemy since they were wearing stolen Union uniforms. Bryson soon discovered their mistake, and he sent a lieutenant to Anderson to make the needed explanation, offer an apology, and propose a union of their forces. Anderson, however, was indignant and refused Bryson’s offer, saying, “Your men are either d – – d fools or worse … or you would not have fired at us. I don’t want anything to do with you or any other of Perkins’s men.” [10]

As a result, “Wash” Bryson was not part of the infamous Centralia Massacre described earlier – nor was he part of the Battle of Centralia that broke out later that day. In fact, he was shot the day before the massacre by Union troops under Major Andrew Vern Emen Johnson, who had been pursuing Bryson and his men. Bryson sent a scout to Centralia to seek medical care and a wagon to carry him to safety. The bullet with which he was shot was the one described above that forty years later caused him injury.

His pursuer, Johnson, was part of Col. Edward A. Kutzer’s 39th Regiment, Missouri Infantry. And while Johnson and his men managed with their bullets to temporarily put a halt to G.W. Bryson’s fighting abilities, they would soon encounter Bryson’s brother James, along with about 400 other Confederate guerrillas, on a battlefield three miles outside Centralia – and few Union troops would survive the day.

(Photo by Tonya McQuade, April 2022)

Tonya McQuade is an English Teacher at Los Gatos High School and lives in San Jose, California. She is a great lover of history, frequently visiting museums and historical sites with her husband and children, as well as reading and teaching historical texts, literature, and primary source documents. After acquiring 50 family Civil War letters in 2022, Tonya began researching the American Civil War in Missouri. She is currently working on a book incorporating the letters with historical commentary, titled A State Divided: The Civil War Letters of James Calaway Hale and Benjamin Petree of Andrew County, Missouri. Tonya earned B.A. degrees in English and Communication Studies from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and served there as a writer and editor for the student newspaper, the Daily Nexus, for four years. She also earned her Single Subject Teaching Credential in English at UCSB and later her M.A. in Educational Leadership from San Jose State University.

Works Cited

- Thiessen, Thomas D., Douglas D. Scott, and Steven J. Dasovich. “This Work of Fiends”: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives on the Confederate Guerrilla Actions at Centralia, Missouri, September 27, 1864, Academia.edu, March 2008, https://www.academia.edu/6909291/_This_Work_of_Fiends_Historical_and_Archaeological_Perspectives_on_the_Confederate_Guerrilla_Actions_at.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Williams, Walter, ed. A History of Northeast Missouri, Volume I. The Lewis Publishing Company, 1913. pp. 220-21.

- Thiessen, Thomas D., Douglas D. Scott, and Steven J. Dasovich. “This Work of Fiends”: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives on the Confederate Guerrilla Actions at Centralia, Missouri, September 27, 1864, Academia.edu, March 2008, https://www.academia.edu/6909291/_This_Work_of_Fiends_Historical_and_Archaeological_Perspectives_on_the_Confederate_Guerrilla_Actions_at.

- Wolnisty, Claire. “Centralia Massacre.” Civil War on the Western Border, https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/centralia-massacre.

- Morelock, Jerry. “For Your Civil War Buff’s Bucket List: Centralia, Mo.” HistoryNet, 29 April 2020, https://www.historynet.com/for-your-civil-war-buffs-bucket-list-centralia-mo/.

- Thiessen, Thomas D., Douglas D. Scott, and Steven J. Dasovich. “This Work of Fiends”: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives on the Confederate Guerrilla Actions at Centralia, Missouri, September 27, 1864, Academia.edu, March 2008, https://www.academia.edu/6909291/_This_Work_of_Fiends_Historical_and_Archaeological_Perspectives_on_the_Confederate_Guerrilla_Actions_at.

- Wolnisty, Claire. “Centralia Massacre.” Civil War on the Western Border, https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/centralia-massacre.

- Switzler, William Franklin. History of Boone County, Missouri. St. Louis. Western Historical Co., 1882.

George Washington Bryson and Josephine America (Mundy) are my Great-gr Grandparents from Boone County Missouri. Their daughter Gertrude Bryson and James Thomas Adams Esq. are my Great Grandparents. They lived in Gainesville, Texas where my Grandmother Gertrude Margaret Adams was born and raised and George Washington Bryson was a rancher. My Grandmother married Richard Graham Patterson of Ardmore Oklahoma.