Colonel Fremantle Attends an Auction of Enslaved Persons

As those familiar with the Gettysburg campaign understand, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Fremantle took leave from the British army in the spring and summer of 1863, journeying to the Confederacy to observe the U.S. Civil War. He famously recorded his thoughts about the Army of Northern Virginia before returning to Britain and publishing them in his book Three Months in the Southern States: April-June 1863. What many might not be aware of is where Fremantle actually spent his time, as only a small part of his journey in the Confederacy was with Lee’s army. Coming into the Confederacy in Texas, he journeyed across the Trans-Mississippi, spent time with Confederate forces in Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia, observed Confederate defenses of Charleston and Wilmington, and finally proceeded up to Virginia in time to join Lee’s army as it marched to Pennsylvania. He recorded military and civilian life in the Confederacy, and in June 1863 attended an auction of the enslaved, providing a unique viewpoint as an international observer to the system of enslavement.

Arriving in Charleston on June 8, Fremantle spent several days inspecting Fort Sumter, walking Morris Island, touring Confederate ironclads, calling on city businessmen, and meeting General Robert Ripley and navy Captain John R. Tucker. At Sumter, already flying the new stainless banner which Fremantle noted “bears a strong resemblance to the British white ensign,” he counted thirteen U.S. warships blockading the port.[1]

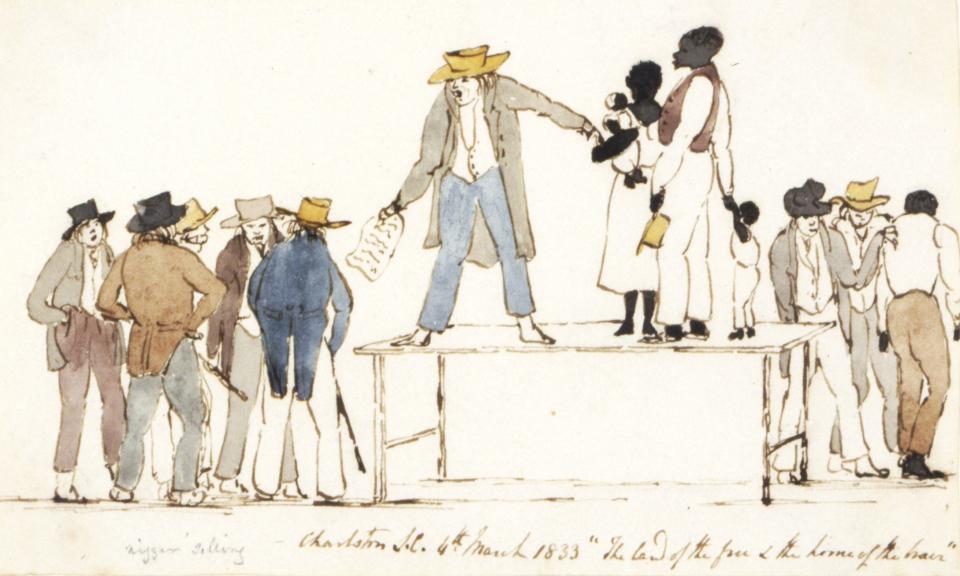

War, even directly against Charleston, did not stop the economics of slavery however, and on his first day in the city Fremantle noted how “a great deal of business is evidently done in buying and selling negroes, for the papers are full of advertisements of slave auctions.”[2] It was apparent from his writings that day that the colonel wished to see for himself how these auctions operated. There was one on June 9, but Fremantle was at Fort Sumter at the time and was unable to attend. It was Fremantle’s fifth day in Charleston, June 12, 1863, that an auction occurred where he could observe.

(Benjamin Dahlhoff, Creative Commons BY 3.0)

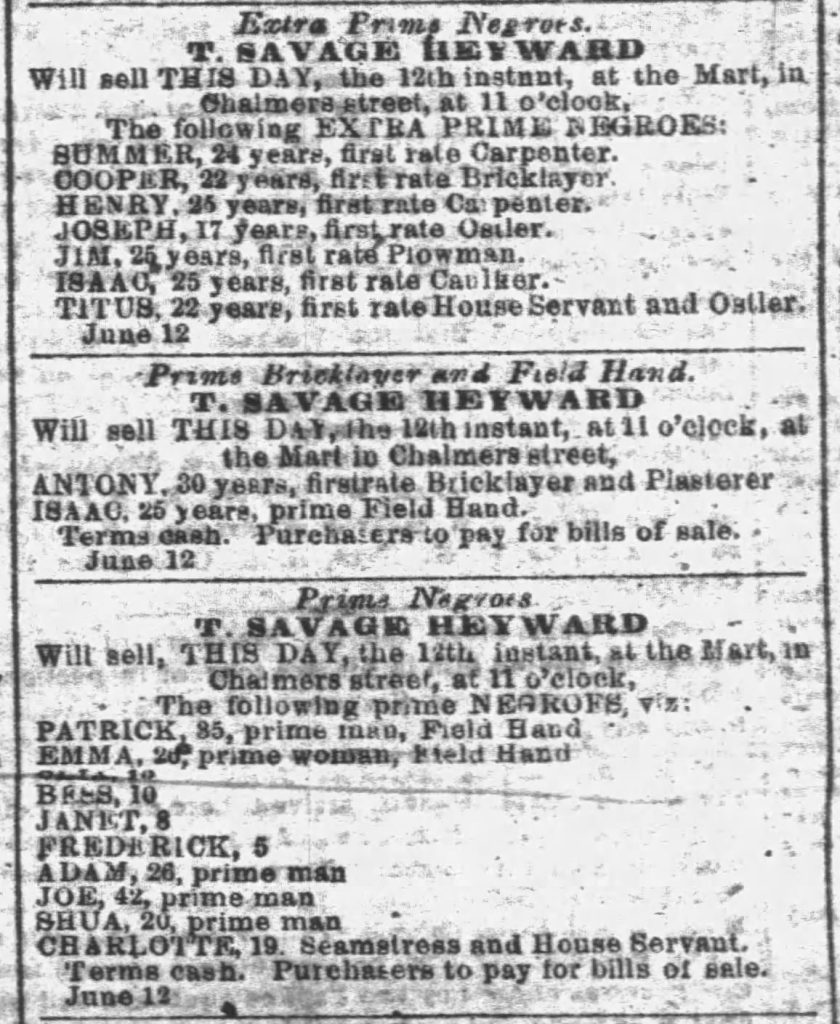

The June 12 auction was hosted by T. Savage Heyward, a local broker, plantation owner, and enslaver who organized and facilitated many auctions of both the enslaved and plantations.[3] It occurred at 6 Chalmers Street in a building known as the slave mart. Scheduled for 11:00 am that morning, Fremantle noted that the entire auction was finished in “only ten minutes” and that “about fifteen men, three women, and three children” were sold.[4] In actuality, the auction was three separate ones from three individual sellers, all facilitated by Heyward. Fremantle was close in the count of enslaved sold that morning, as it was actually eighteen persons sold, twelve adult men, two adult women, and four children with advertised skillsets ranging from bricklayer to carpenter to seamstress to field hand.[5] It was possible that there was one family amidst those being sold, as a man named Patrick, woman named Emma, and four children named Clia, Bess, Janett, and Frederick were all listed one after the other before other adults were listed on the advertisements of sale. Two of the sellers demanded cash payments at the auction itself.

The number of enslaved persons sold that day seemed typical for Charleston that summer of 1863. The June 9 auction Fremantle missed because he was touring Fort Sumter included 22 persons, including “a very likely and intelligent family” of husband Jacob, wife Mary Ann, and five children ranging in age from sixteen to three years old.[6] Another auction on June 16 the week after the one Fremantle observed included the sale of 28 enslaved persons “accustomed to the culture of rice and provisions,” as well as a plantation called Cypress on the Combahee River, presumably the plantation where the enslaved persons worked and lived.[7]

Being a foreigner who was presumably attending his first auction of enslaved persons, Fremantle was upset by what he witnessed. Those being sold “were seated on benches” until called to a stage for the auction. Afterwards, Fremantle observed “buyers opening the mouths and showing the teeth of their new purchases to their friends in a very business-like manner.” Overall, the English lieutenant colonel remembered it was “not a very agreeable spectacle.”[8] He makes no mention if there was family and if so, whether they were sold together or separated.

(Digital Public Library of America)

Though Fremantle disliked witnessing the buying and selling of persons firsthand, his journal entry that day explains his indifference to the system of Confederate enslavement as a whole. “Many influential men in the South feel humiliated and annoyed with several of the incidents connected with slavery,” he wrote that day, “and I think that if the Confederate States were left alone, the system would be much modified and amended, although complete emancipation cannot be expected.”[9] His disagreeable observation of the auction also did not affect his temperament for the rest of the day, for one hour after the auction Fremantle was touring Confederate ironclads. He also met with General Pierre G.T. Beauregard that evening.

Fremantle’s opinion about Confederate enslavement was framed not just by his observation of the auction that day, but also after having “a long talk” with an enslaved woman on a wagon in Texas that April, having an enslaved man clean his boots at a hotel in Houston, speaking with an enslaved man driving a wagon in Mississippi, and touring slave quarters in Mississippi that Fremantle believed were “comfortable and very clean.[10] He remembered seeing one enslaved woman in late May who “must have benefited largely by the ‘peculiar institution,’” as she “was evidently … treated with affection and care.”[11] He also observed two plantation from a distance, one in Texas and another in Louisiana, though it should be noted Fremantle did not receive close tours of these plantations or interview any enslaved persons working on them, and most of the enslaved persons Fremantle encountered were either working in urban areas, were with their enslavers attempting to evade U.S. military movements, or were enslaved persons granted more autonomy than most by being hired out to work more independently.

(Charleston Daily Courier, June 12, 1863)

There is one more thing worth mentioning regarding Fremantle’s experience with the June 12, 1863, Charleston auction. In his diary that day he wrote many Southerners “had never seen a negro sold by auction, and never wished to do so. It is impossible to mention names in connection with such a subject.”[12] Though Fremantle was speaking about keeping those opposed to slavery in the Confederacy unnamed, the idea that it was “impossible to mention names in connection with such a subject” is only referring to Anglos in the South opposed to the institution. I am sure that the eighteen enslaved persons sold that June day in Charleston were quite opposed to the system, and we actually know their names. It would only be a small piece of justice to identify them here:

Patrick, 35-year-old man

Antony, 30-year-old man

Adam, 26-year-old man

Emma, 26-year-old woman

Henry, 25-year-old man

Isaac, 25 -year-old man

Isaac, 25-year-old man

Jim, 25-year-old man

Summer, 24-year-old man

Cooper, 22-year-old man

Titus, 22-year-old man

Shua, 20-year-old man

Charlotte, 19-year-old woman

Joseph, 17-year-old man

Clia, 12-year-old girl

Emma, Bess, 10-year-old girl

Janett, 8-year-old girl

Frederick, 5-year-old boy

Endnotes:

[1] Arthur Fremantle, Three Months in the Southern States: April-June 1863, (London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1863), 186.

[2] Ibid., 181.

[3] T. Savage Heyward to James L. Orr, January 2, 1863, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, 1861-1865, Roll 0440, M346, RG 109, U.S. National Archives.

[4] Fremantle, Three Months in the Southern States, 193.

[5] “Auction Sales,” Charleston Mercury, Charleston, SC, June 12, 1863.

[6] “Auction Sales,” Charleston Daily Courier, June 8, 1863.

[7] “Auction Sales,” Charleston Mercury, Charleston, SC, June 12, 1863.

[8] Fremantle, Three Months in the Southern States, 193.

[9] Ibid., 194.

[10] Ibid., 37, 63, 99, 119.

[11] Ibid., 119.

[12] Ibid., 193-194.

Interesting article! Thanks, Neil!

Excellent article! However, General Ripley was Roswell. Robert Ripley, believe it or not, was an entrepreneur of a later period.

Ack! You are right about General Ripley. Not sure how that slipped past my eyes when writing this one. Thanks for pointing it out.

Really interesting Neil, thank you. That little factoid about it only taking TEN MINUTES has really stuck with me since reading this yesterday.

I read the names out loud. Thanks for this opportunity.

A superb write up.

Freemantle didn’t actually attend the auction. To be clear, his June 12th entry states, “They were so quick about it that the whole affair was over before I arrived.” on page 193. He wrote they “… were seated on benches looking perfectly contented and indifferent.” He writes “… not a very agreeable spectacle to an Englishman” and that people told him “they had never seen a negro sold by auction, and never wished to do so.” That is about as close to critical of slavery as he gets, whereas over and over again throughout the south he describes slaves’ loyalty to their masters, and ends his diary with northerners of New York City rabidly trying to kill black people during the race riots, including black crewman on British ships.