At War’s End: Danville, Martinsville, and the Final Days of the Civil War

ECW welcomes guest author Jarred Marlowe

By April 2, 1865, hope for the Confederate State of America was dwindling fast. After the colossal failure at the Battle of Five Forks the day before, General Ulysses S. Grant decided to attack General Robert E. Lee’s army heavily fortified in the earthworks at Petersburg. Unable to sustain them as a defensible position, Lee began his retreat and sent word to Confederate President Jefferson Davis advising him to flee Richmond. We all know what became of Lee’s army several days later, and most know that Davis and the Confederate government hastily fled Richmond and ended up establishing the new government headquarters in Danville, Virginia. But not many know that the war could have ended in Danville with Davis’s capture before Lee surrendered, and it came very close to happening.

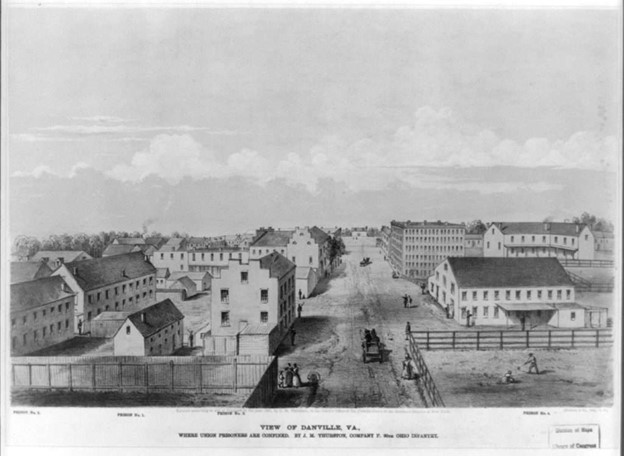

Danville was one of the few Southern cities that saw growth and prosperity throughout the Civil War. The city’s population grew from around 3,500 at the outbreak of the war to 5,000 by war’s end. Danville’s claims to fame at the time were being a large market for tobacco (eventually to become one of the world’s biggest tobacco markets) and the fact that the city was a railroad hub for both the Richmond and Danville Railroad and the newly constructed Piedmont Railroad, which connected Danville to Greensboro, North Carolina. From Danville, supplies were sent to Confederate soldiers all over the South. Confederate Commissary General Isaac M. St. John had over 500,000 bread rations and 1.5 million meat rations stored in the Danville warehouses at any given time in the latter part of the war. Also, Danville came to be a central site for Union army prisoners with about 7,500 soldiers being imprisoned in the city between November 1863 and April 1865.

When Davis and the Confederate government fled Richmond for Danville, they arrived to find a city that was well-supplied, but not very well defended. Construction on earthworks for the city had begun the previous year by detained Union prisoners, but construction stopped shortly after due to an incident where 75 prisoners on a work detail had escaped. Several cannons were placed on bluffs around the city, but apart from those cannons, little was in place to defend what was now the makeshift headquarters of the Confederate States of America. After Davis settled in to his new home and office in Danville’s Sutherlin Mansion, one of his first orders was to have construction on the earthworks resumed and finished. Unfortunately, he would not be in Danville long enough to see his plans come to fruition.

A few days after Davis arrived in Danville, something happened just to the west of him that could have changed the whole ending of the war. George Stoneman and his cavalry had been tearing through southwestern Virginia in early April 1865 and by April 7, a division of Stoneman’s cavalry commanded by General William Palmer camped at Reed Creek near the Smith River just outside of Henry Court House, more commonly known as Martinsville. Intelligence provided to Palmer by a former slave alerted him to a large Confederate military presence on the other side of town. Bivouacked on Jones Creek about a mile north of the center of town were about 250 Confederate cavalrymen led by Colonel James T. Wheeler. He had been ordered to leave his position in the Lynchburg area and join Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s forces in North Carolina, much to the chagrin of Gen. P.G.T Beauregard, who had been tasked with command of southern Virginia and northern North Carolina. Beauregard had asked Johnston for men to help secure Danville since even before Davis had arrived, but received no such help from Johnston.

On the morning of April 8, Palmer’s forces rode east from Reed Creek to Jones Creek and surprised the Confederate forces there who were just waking up to make their breakfast. There was a brief skirmish that left five Union soldiers and one Confederate soldier dead and many others wounded. The Confederates retreated east towards Danville, where Wheeler sent word to Beauregard: “At dark tonight, the enemy was still in Henry Courthouse. During the day he was reinforced by about 800. They tell citizens that they will advance on Danville in the morning; as yet no buildings have been burned in town.” Makeshift field hospitals were created in the homes and buildings in Martinsville, while Palmer’s remaining soldiers went and gathered what supplies they could from local residents. Those soldiers also relayed to the townspeople the notion that Danville was the next target for Stoneman and Palmer.

It is unclear how much Stoneman or anyone around him knew about Davis’s arrival and stay in Danville. What is known though is that after retreating east after the skirmish at Jones Creek, Wheeler and his men did not stay long and continued south towards Johnston, leaving no buffer between Palmer and the defenseless Danville. If Palmer had wanted to ride 29 miles to the east and capture the resource-rich Danville, or if Stoneman had wanted to abandon his central objective of destroying Confederate railroads and manufacturing centers to gain a central city on what was left of the Confederate States of America, the war could have ended in Danville with Jefferson Davis and the entire Confederate government and treasury being captured before Lee could sign off on the surrender. Instead of going east like his soldiers had threatened, Palmer and his forces marched southwest when they left Martinsville. They rejoined Stoneman who had been camped in Taylorsville, Virginia (modern day Stuart) in Danbury, North Carolina and together rode south towards present day Winston-Salem. Jefferson Davis fled Danville on April 10th and headed south on the Piedmont Railroad to Greensboro, narrowly avoiding capture along the way.

Jarred Marlowe is a historian who currently lives in Collinsville, Virginia. He has a bachelor’s degree in history from the Virginia Military Institute and master’s degree from Johnson University. Jarred is the president of the Col. George Waller Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution and a member of the Blue & Gray Education Society.

Sources

Calkins, Christopher. “The Danville Expedition of May and June 1865.” The Papers of the Blue & Gray Education Society, Number 8, September 17, 1998, 5–36.

Hartley, Chris J. Stoneman’s Raid 1865. Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair Publisher, 2010.

Hyde, Solon. A Captive of War. Shippensburg, PA: Burd Street Press, 1996.

Secretary of War, and Daniel S. Lamont, 1 The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies § (1897).

How fascinating! Thank you for this interesting article.

Thank you! I appreciate your feedback.

Thank you for sharing this research, Jarred! Danville has been on my travel bucket list for a while…maybe it just moved up a few places.

Thank you for the feedback! Danville is a great place to spend a day. It’s actually my hometown and where I grew up so Danville will always be special to me.

Sarah, before you visit Danville, you may find the following of interest: Robertson, James I., “Danville under Military Occupation, 1865.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 75, no. 3, 1967, pp. 331 & n. 2. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4247324.

I also forgot to mention that I just bought your book on the Battle of New Market a couple of weeks ago! As a VMI grad, I am very much looking forward to reading it!

Thank you for this interesting story raising another Civil War “what if.” You mention Davis’ later narrow escape out of Danville on the way to Greensboro. Indeed, the presidential train escaped only minutes before a Union force burned the railroad bridge over which they had traversed. Told of his narrow escape, Davis quipped: “A miss is as good as a mile [sic].”

Thank you, Kevin! I grew up in Danville and now live in Martinsville and when I learned of both stories happening simultaneously, my mind raced with possibilities. And in this instance, I will have to agree with Davis on that one.

Good stuff!

Thank you so much!