The Wheeling Horse Hospital

ECW welcomes guest author Christy Perry Tuohey

“The Civil War was a war of animal power. Thousands of horses accompanied the armies of both sides, pulling artillery and supply wagons, carrying cavalry, cannoneers, and officers. They provided the power for transportation and communication, and made possible the kind of fighting that occurred, and the war’s scope and scale.”

–Ann Norton Greene, Horses at Work: Harnessing Power in Industrial America

Despite the incredible wear and tear horses endured during the war, you would have been hard pressed to find a certified U.S. Army veterinarian in 1861. There were only 15 qualified, educated veterinarians in the U.S. in 1847 and none in any United States military branch between the Revolutionary and Civil wars.[1] It wasn’t until the latter war’s outbreak that the Union government made any efforts toward animal care, and even then the Army only required each regiment to have a farrier—a horseshoe maker and fitter—to take care of all Union equines’ needs.

Later on in the war, according to the Army Medical Department Center of History and Heritage, each regiment of cavalry was authorized to have a regimental veterinary surgeon with the rank commensurate with sergeant major.[2] But not all regiments opted for these officers, and it was common for regular soldiers to be put in charge of horse care.

This glaring gap in animal military medicine makes Civil War Assistant Quartermaster William R. Downing’s success in treating and healing Civil War equines all the more remarkable. He reportedly used little medicine and lots of Ohio River water to cure his patients.

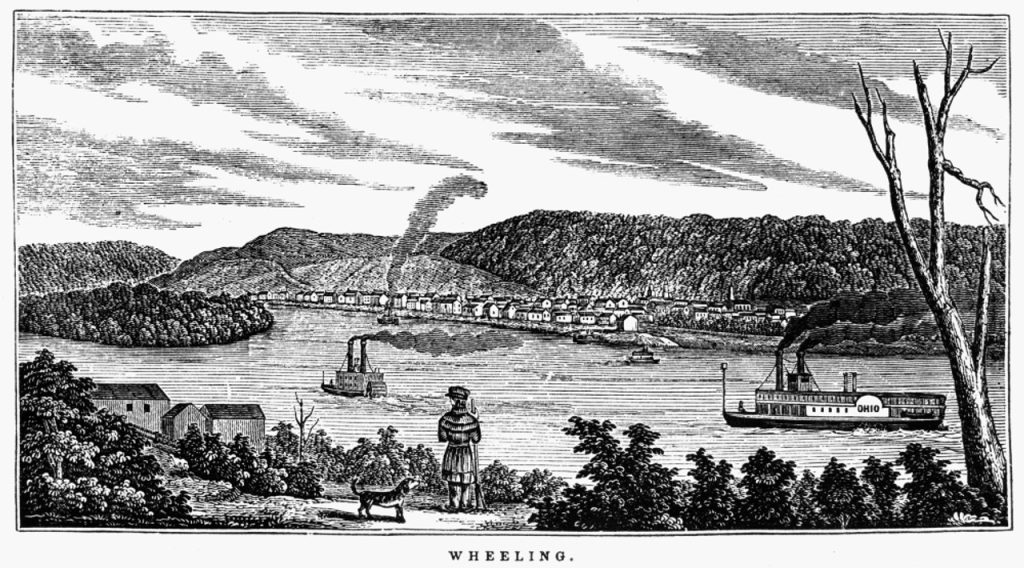

William R. Downing, 53, was tending his farm in Chester County, Pennsylvania when he was offered an appointment of assistant quartermaster of volunteers with the rank of captain in the Union Army. He immediately accepted the assignment and by late 1861, was stationed at Wheeling, Virginia. It soon became evident that Downing’s knowledge of horses made him an ideal candidate for the position.

About seven months into the war, Captain Downing advertised in a Wheeling newspaper for 100 horses “suitable for artillery service in the U.S. Government.” A week later, having purchased the lot, he put them on the steamer Capitola at Wheeling, which left for Gauley Bridge, Virginia. That area had just been the scene of two battles, including a Union rout at Cross Lanes and the Battle of Carnifex Ferry, where Union General William S. Rosecrans was victorious over former Virginia governor General John B. Floyd.

A description of just how perilous the topography of southwestern Virginia was for both man and beast shows up in a report that Brigadier General Jacob D. Cox wrote from Gauley Bridge. “The whole ground is exceedingly difficult to climb, the mountain sides being very rocky, and in many places almost perpendicular, and the most determined bravery and perseverance were evinced by the troops.”[3]

In a subsequent feat of mountain engineering that undoubtedly required horsepower, Major Samuel Crawford, 13th U.S. Infantry, wrote of operations at Townsend’s Ferry on the New River. A Union officer’s reconnaissance determined that Union troops could only cross the New over a system of floats, created with wagon beds, that had to be lowered down over a plunging cliff. “In some places the entire material had to be carried over rocks to the heads of steep ravines, down which the skiffs and wagon beds were sent by means of ropes.”[4]

In the spring of 1862, another steamboat brought sick and injured horses to Wheeling from hard duty in “the Kanawha country.” Captain Downing was soon authorized to receive horses worn out by the armies in West Virginia, and dozens were sent to him from points all along the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.

Local observers were shocked by the horses’ appearance. “We never before saw such a melancholy, ghostly looking lot of skeletons,” a local newspaper editor wrote. “Their sides looked like washboards and their ribs can be counted as far as they can be seen. Their backs were scarred and their limbs and bodies were covered with wounds, sores and running corruptions. They have evidently been beaten, driven, ridden, and starved without mercy.”[5]

By year’s end, AQM Downing had established a hospital for ”dilapidated and indigent horses” on Wheeling Island. Pre-war fairgrounds on the island were being used for a Union training camp; the government turned the exhibition halls and animal stalls into barracks for soldiers, and Downing used some for horses. The location also provided plentiful access to the surrounding Ohio River.[6]

“He has now some fifty or sixty under treatment,” the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer reported. “The course of treatment is a very remarkable one. No medicine is required and the Captain has been remarkably successful. The system practiced is the hydropathic. Those that are stiff in the limbs, which is a very popular infirmity, are made to stand in the water up to their knees…”[7]

The newspaper was soon making playful reference to the assistant quartermaster’s “hoss hospital,” “horsepital,” and “Captain Downing’s water cure establishment.” In fact, cold water hydrotherapy is still used internationally today, particularly for rehabilitating athletic horses.[8] It’s not known whether Downing had any veterinary training or if he was simply using his farm animal experience, but news reports indicate the treatment was helpful for many of the horses brought to the island.

“Captain Downing uses very little medicine, except of a vegetable character, and his success so far has been very remarkable. He has already resurrected a number of horses which had been turned out of the army as perfectly useless.”[9]

During his time at Wheeling, Downing bought around 9,000 horses for government use at the average price of $110 per head. He rehabilitated and either returned to service or sold for non-military purposes hundreds more. He had also bought nearly two million bushels of oats and about the same amount of corn, as well as having bought and shipped four thousand tons of hay.[10]

Well after the war ended, in 1879, the U.S. Congress passed a resolution that required all applicants for military veterinary positions to be graduates of a recognized veterinary college. But over the course of his wartime tenure, civilian horse doctor William Downing treated hundreds of horses mostly with farm wisdom and water.

Christy Perry Tuohey is an author and a 30+ year veteran of newsrooms and classrooms. She was a TV news reporter, anchor, host, writer and producer in markets including Charleston/Huntington, WV; Charlotte, NC; Columbus and Cleveland, OH; and Syracuse, NY. She has written for a number of print and digital publications. In the 2000s, she taught journalism classes at Syracuse University. Her most recent book, A Place of Rest for Our Gallant Boys: The U.S. Army General Hospital at Gallipolis, Ohio, 1861-1865, was published by 35th Star Publishing (Charleston, WV).

[1] “Every Man His Own Horse Doctor,” Katie Reichard and Amelia Grabowski, Authors, National Museum of Civil War Medicine blog, https://www.civilwarmed.org/animal/

[2] “The U.S. Army Veterinary Corps Turns 90,” Andy Watson, AMEDD Regimental Historian, author; The AMEDD Historian newsletter, Number 3, Summer 2013, P.8.

[3] Report of Brigadier General Jacob. D. Cox, U.S. Army, of skirmishes at Blake’s farm, November 10-11, War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Civil War, Serial 005, Page 272, Operations in Md., N.Va., and W.Va., Chapter XIV, P. 272

[4] Report of Major Samuel W. Crawford, Thirteenth U.S. Infantry, of operations at Townsend’s Ferry, War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Civil War, Serial 005, Kanawha and New River, W.Va., Chapter XIV, Page 275

[5] “Captain Downing’s Horsepital,” Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, February 4, 1863, P.3.

[6] Camp Carlisle Union Camp at Wheeling Island, The Historical Marker Database, found at https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=92543

[7] Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, December 31, 1862, Page 3.

[8] “International Survey Regarding the Use of Rehabilitation Modalities in Horses,” Wilson, McKenzie, Duesterdieck-Zellmer, authors; Frontiers in Veterinary Science journal, June 11, 2018. National Center for Biotechnology Information, found at PubMed Central, National Library of Medicine, https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.wvu.idm.oclc.org/pmc/articles/PMC6004390/

[9] Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, February 10, 1863, Page 3.

[10] Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, April 2, 1863, Page 3.

An unsung hero, thank you for this.

Artillery Colonel Charles Wainwright’s published diary is full of the status of his horses and the men that took care of them. According to him, the better the soldier the better the condition of his horses.

A friend who owns a few horses says they basically bought their veterinarian a travel vehicle with all they paid him.

Thanks for the info on Col. Wainwright, Henry! I will look up his diary, sounds interesting.

I would like to see a full-blown treatment of horse/mule management. Hess’ “Civil War Field Artillery” has the most detail I have come across, but there is room for much more.