Accused of Spying: Fannie Cowper of Suffolk, Virginia

ECW welcomes back guest author Jeff T. Giambrone

In January 1866, former Confederate general Samuel G. French received a letter from Frances D. “Fannie” Cowper of Suffolk, Virginia. He had only met the young lady once, in 1863, when he placed her under arrest and charged with being a Union spy. One can only imagine the look on French’s face when he read the following:

Gen., In looking over the items of the “news” your name met my eye which called up many unpleasant memories and a desire to write your excellency a letter, not to plead for mercy this time but to give you a few of my opinions of you and your treatment of me while a prisoner in your hands. It is almost unnecessary for me to say that at that time [I] formed a most unfriendly and unfavorable opinion of you, which I answer you time has not the least modified. And the recollection of the harshness injustice and harmful treatment which I experienced at the hands of you and your subordinates causes my bosom to swell with just indignation.

Fannie had opened by giving the general both barrels of her wrath, and she was only building steam as she wrote the following:

In thus addressing you and endeavoring to express my indignant feelings towards you, and my supreme contempt for you. I do not pretend to think I shall arouse your sentiment, or touch your conscience. Knowing full well that you are devoid of all manliness, spirit, chivalrous sentiment, and sensibility. But if I am mistaken and you should feel your self wrong[ed] by my accusations, you can excuse me by admitting my experience leads me to be severe. An experience I now look back to with shuddering and most painful emotions.

With tongue firmly in cheek, Fannie closed the letter with one last jab at French:

In conclusion, your excellency will accept my warmest regards and sincere thanks for the kindness shown to me while in your care and believe me I shall ever remember it with the liveliest feelings my gallant captain, my New Jersey friend and champion.[1]

General French’s immediate reaction to the letter was to take out his pen and write on the top of the first page of the letter; “Fannie D. Cowper. Contains many false statements. She was a spy.” In addition, he added this postscript to the second page of the document: “The writer of this letter was a ‘spy.’ I heard she was coming across our lines from numerous persons and had her arrested in Petersburg, Va., and sent back to Suffolk. I never saw her but once. She was treated kindly living at the hotel but not permitted to leave it.”[2]

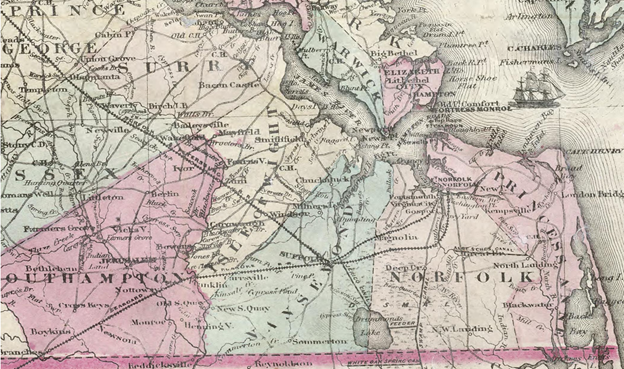

Frances D. “Fannie” Cowper was the eldest child of Joseph and Narcissa Cowper of Suffolk, Virginia. Located about 24 miles east of Norfolk, Suffolk was described as being a “small rural community with a cluster of brick and wooden buildings fronting tree-lined streets.”[3] By 1860 the Cowper family included in addition to 21 year old Frances, son Henry aged 18, and daughters Ophelia, 14, Jennie, 6, and Nelly, 4. The family patriarch Joseph was a local merchant in Suffolk who was appointed town postmaster in 1853.[4] The Cowpers suffered a heavy blow in the fall of 1860 when Joseph died of liver disease at the age of 48.[5] The family was fortunately able to stave off potential financial disaster when Narcissa was appointed to take over her husband’s job as Suffolk postmaster.[6]

The Cowpers had weathered a personal tragedy, but the political storm of 1861 and the eventual secession of the Southern states proved an even greater trial. When Virginia voted in favor of leaving the Union on April 17, 1861, the family found themselves behind enemy lines as they still supported the United States government.

As known Unionists, life in Suffolk was not easy for the Cowper family, even though son Henry had joined the Confederate Army in November 1862.[7] Narcissa wrote that “the sentiments of the family being known by the Secessionists there, we were daily insulted and vilified by them.”[8]

The family found relief from the harassment of their neighbors in the spring of 1862, when the Peninsula Campaign compelled the evacuation of Confederate forces from Suffolk. The town was occupied by the Union army on May 12, 1862.[9]

In March 1863 Fannie left the safety of Union-occupied Suffolk to travel into enemy-held territory, and her trip had not gone unnoticed by the Confederates. Fannie claimed in her letter to General French that she made the trip to visit her brother and to obtain money for her family.[10] French, however, told a different story in his memoirs concerning Fannie and her motivation for traveling:

There was a girl living in Norfolk that wanted to cross the lines and go to Richmond. Three prominent citizens, separately, informed me that she was a spy. Gen. J.J. Pettigrew, on the Blackwater, received like information, and asked me for instructions.[11]

In a letter to Union authorities, Narcissa Cowper documented what had happened to Fannie after her arrest:

In the month of March 1863, my eldest daughter was arrested by the so styled Confederate authorities, on the charge of being a spy for the commander of the Federal forces then at Suffolk. After being confined for a couple of weeks, she was, without any of the charges against her being proven, sentenced to be sent to Fort Salisbury N.C., but the sentence was revoked and she was sent to her home in Suffolk.[12]

Fannie was safely back in Suffolk after her harrowing ordeal, but the respite was only temporary. On July 3, 1863, Federal forces evacuated Suffolk, as they felt it was no longer worth the effort to hold.[13] With Federal protection gone, Narcissa Cowper made the decision to pack up her family and flee to Union-held Portsmouth, Virginia. She later justified this decision, saying,

many threatening messages were sent in to my daughter by different rebel commanders of the troops on the Blackwater, saying if they ever had had her in their power again, they would place her in prison, where she could do no more harm.[14]

Fannie agreed with her mother’s decision to refugee to Portsmouth, admitting in a letter to a Union officer that “I dare not go back to meet slight, unjust condemnation and imprisonment.”[15]

The Cowper family spent the remainder of the war in Portsmouth, and they had regular correspondence with Union officers stationed there. In none of the surviving letters does Fannie or anyone in her family claim that she was a spy. In fact, in one letter Narcissa stated unequivocally that “without of the charges which were brought against her being proven, of which it is needless for me to say she was innocent.”[16]

Unfortunately, no wartime Confederate documents have surfaced that would shed light on the arrest of Fannie Cowper. Certainly, General French believed she was a spy. In his memoir, he noted the following about Fannie:

In 1866 she wrote me a letter declaring all I heard about her was false, and wishing me all sorts of bad things. All in all it would have been an interesting case for Sherlock Holmes.[17]

Rather than being a spy, Fannie Cowper was probably an innocent girl who was targeted by her Confederate neighbors for the crime of supporting the Union during the war. The Cowper family never claimed she was a spy, and in fact Narcissa Cowper stated that Fannie was not guilty of the charges. She made this statement to General Shepley at a time when the family was seeking Union aid to remain in their rented house at Portsmouth. Having a daughter who was a spy for the Union would almost certainly have aided their case.[18] It seems that General French was all too willing to believe the rumors about Fannie, a decision for which she most certainly did not forgive him after the war.

Jeff T. Giambrone is a native of Bolton, Mississippi. He has a B.A. in history from Mississippi State University and an M.A. in history from Mississippi College. He is employed as a Historic Resources Specialist Senior at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Giambrone has published four books: Beneath Torn and Tattered Flags: A Regimental History of the 38th Mississippi Infantry, C.S.A.; Vicksburg and the War, which he co-authored with Gordon Cotton; An Illustrated Guide to the Vicksburg Campaign and National Military Park; and Remembering Mississippi’s Confederates. In addition, he has written articles for publications such as North South Civil War Magazine, Military Images Magazine, Civil War Monitor, and North South Trader’s Civil War Magazine.

[1] Frances D. Cowper to Samuel G. French, 27 January 1866. Samuel G. French Papers, Z/0112.000/S, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, MS.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Wills, Brian Steel. The War Hits Home: The Civil War in southeastern Virginia. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2001, 16-17.

[4] 1850 United States Census, Nansemond County, Virginia, page 129a. Accessed on Ancestryinstitution.com, July 12, 2023; U.S., Appointments of U.S. Postmasters, 1832-1971. Accessed on Ancestryinstitution.com, July 12, 2023.

[5] Virginia, U.S. Death Registers 1853-1911. Accessed on Ancestryinstitution.com, July 12, 2023.

[6] Register of officers and agents, Civil, military, and naval, in the service of the United States, on the Thirtieth September, 1861: Showing the state or territory from which each person was appointed to office, the State or country in which he was born, and the compensation, pay, and emoluments allowed to each: The names, force, and condition of all ships and vessels belonging to the United States, and when and where built: Together with the names and compensation of all printers in any way employed by Congress, or any department or Officer of the Government (1862). Washington, D.C.: G.P.O., page 163.

[7] Henry D. Cowper served in Company I, 13th Virginia Infantry, from 1862-1865. Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Virginia, 13th Cavalry. Accessed on Fold3.com, October 17, 2023.

[8] Narcissa S. Cowper to General George F. Shepley, 2 October 1864. Union Provost Marshals’ File of Paper Relating to Individual Civilians; file of N.S Cowper. Accessed on Fold3.com, August 8, 2022. Note: On Fold3.com the name was misread in the transcription and it is filed under M.S. Cowper.

[9] Wills, Brian Steel. The War Hits Home: The Civil War in southeastern Virginia. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2001, 49-51.

[10] Frances D. Cowper to Samuel G. French, 27 January 1866. Samuel G. French Papers, Z/0112.000/S, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, MS.

[11] French, Samuel Gibbs. Two wars: An autobiography of general Samuel G. French, an officer in the armies of the United States and the Confederate States, a graduate from the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, 1843. Nashville, TN: Confederate veteran, 1901, 156-157.

[12] Narcissa Cowper to Major Webster, 29 September 1864. Union Provost Marshals’ File of Paper Relating to Individual Civilians; file of Narcissa Cowper. Accessed on Fold3.com, October 20, 2023. Note: On Fold3.com the name was misread in the transcription and it is filed under Narcissa Cooper.

[13] Wills, Brian Steel. The War Hits Home: The Civil War in southeastern Virginia. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2001, 192-193.

[14] Narcissa Cowper to Major Webster, 29 September 1864. Union Provost Marshals’ File of Paper Relating to Individual Civilians; file of Narcissa Cowper. Accessed on Fold3.com, October 20, 2023. Note: On Fold3.com the name was misread in the transcription and it is filed under Narcissa Cooper.

[15] Frances D. Cowper to Major Webster, 1 October 1864. Union Provost Marshals’ File of Paper Relating to Individual Civilians; file of Narcissa Cowper. Accessed on Fold3.com, October 20, 2023. Note: On Fold3.com the name was misread in the transcription and it is filed under Narcissa Cooper.

[16] Narcissa S. Cowper to General George F. Shepley, 2 October 1864. Union Provost Marshals’ File of Paper Relating to Individual Civilians; file of N.S Cowper. Accessed on Fold3.com, August 8, 2022. Note: On Fold3.com the name was misread in the transcription and it is filed under M.S. Cowper.

[17] French, Samuel Gibbs. Two wars: An autobiography of general Samuel G. French, an officer in the armies of the United States and the Confederate States, a graduate from the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, 1843. Nashville, TN: Confederate veteran, 1901, 157.

[18] Narcissa S. Cowper to General George F. Shepley, 2 October 1864. Union Provost Marshals’ File of Paper Relating to Individual Civilians; file of N.S Cowper. Accessed on Fold3.com, August 8, 2022. Note: On Fold3.com the name was misread in the transcription and it is filed under M.S. Cowper.

Having lived most of my life here in SE Virginia, I enjoyed the post. One correction, though, Suffolk is west of Norfolk, not east of it. The only things east of Norfolk were Princess Anne County (now the city of Va. Beach where I live) and the Atlantic Ocean.

Thanks for the comment! You are correct, Suffolk is west of Suffolk, not east – a geographic mistake on my part.

Cool story, well written. I have become a fan of Fannie. What an eloquent defense and put down of Major General French. I was surprised that her brother’s enlistment in the Confederate army didn’t seem to help her.

Thank you very much for the comment! I don’t think the Confederate authorities were willing to cut Fannie any slack because she and her family were so outspoken in their support for the Union. When the family was forced to flee Suffolk in 1863 after Federal troops were withdrawn from the city, a newspaper noted: “We learn that a few citizens of the town, who had become charmed with the Yankees, left with them. Among these the widow and daughters of Joseph G. Cowper, for some years postmaster at that place, and Mrs. Cowper was Post Mistress at the time of its evacuation by our troops in May 1862.” (Wilmington Journal, Wilmington, North Carolina, July 16, 1863)

Thanks for making those excellent points, so interesting! Great article!

It doesn’t really appear that she was treated badly. Interesting story.

Fannie sounds like a “high maintenance” sort of person. She may have acquired adversaries for more personal sorts of reasons.

Tom

I don’t know that she was “high maintenance,” but she certainly was not shy about speaking her mind when she felt put upon. In 1864 the Cowper family was living in a rented home in Portsmouth and the Rebel owner of the building was trying to have them evicted. The Cowpers appealed to the Union authorities at Portsmouth to have the eviction stopped. In a letter to a Major Webster in January 1864, Fannie wrote, “You gave Dr. Jarvis a rank secessionist, a man of means with a comfortable home of his own, authority to put us in the street if he chose and he is none too good to do it…Alter your decision, and give us at least three months to help ourselves. In that time, we can get a house, or we shall go home. Better be there with Rebels, traitors, guerillas and enemies than to be in this fix insulted driven about like we are nothing.”