Only the Bare Necessities

ECW welcomes back guest author Brian D. Kowell

In early July 1864 Major General William T. Sherman followed General Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee to the banks of the Chattahoochee River northeast of Atlanta, Georgia. Johnston’s army was entrenched in formidable defenses that one modern historian likened to the Maginot Line.[1] Sherman was determined to cross the Chattahoochee, but following the bloody attacks of June 27 against Johnston’s entrenchments at Kennesaw Mountain, he was reluctant to order another costly direct advance against such a strong position. Sherman personally examined the lines and rejected all notions of frontal assaults. From his headquarters in the Hardy Pace house near Vinings Station he sent orders to find crossing points on the enemy’s flanks.

On July 8 and 9, Major General John M. Schofield selected a crossing at Isom’s Ferry where Sope Creek entered the Chattahoochee on Johnston’s right flank. Schofield’s cavalry, under brigadier generals Kenner Garrard and Edward S. McCook was successful in crossing the river at Shallow Ford, about a mile below Roswell Bridge, and at Cochran’s Ford, half a mile below Sope Creek.[2]

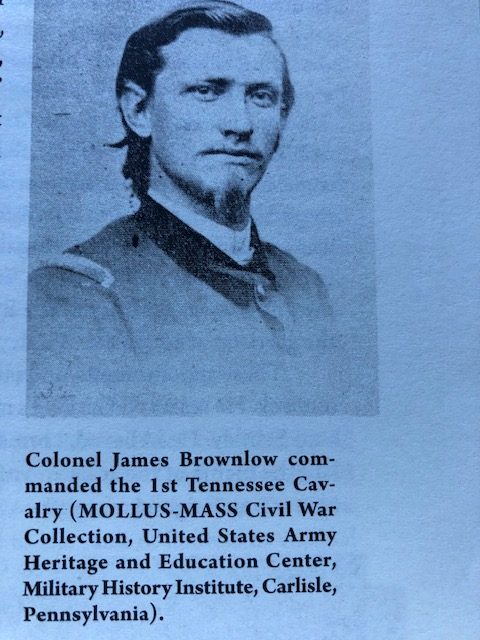

McCook ordered the 1st Tennessee Cavalry to cross at Cochran’s Ford. He recorded the following report of the regiment’s exploits under the command of Colonel James P. Brownlow:

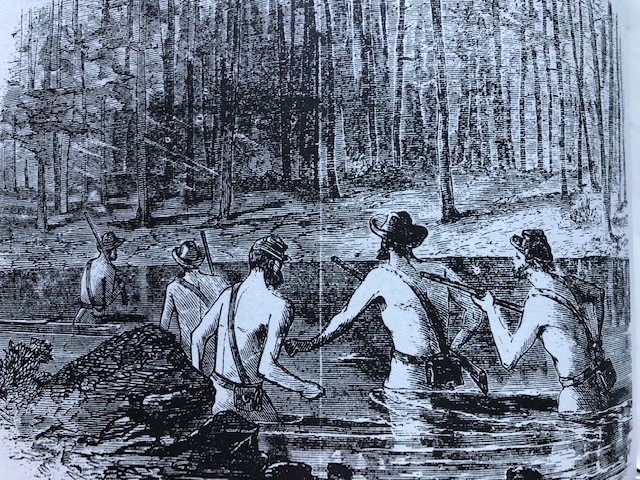

Brownlow performed one of his characteristic feats today. I had ordered a detachment to cross at Cochran’s Ford. It was deep, and he took them over naked, nothing but guns, cartridge-boxes, and hats.[3]

The 6-foot, 6-inch, 21-year-old Brownlow was trying to stealthily cross the river to surprise the Confederate pickets stationed there. As the troopers forded the river, their feet were cut by sharp stones. Brownlow, who had joined the expedition, was the son of Parson Brownlow, a well-known abolitionist minister and newspaper editor. When one of his men let out an oath upon cutting his foot, Brownlow, not wanting any noise alerting the enemy, proclaimed, “The occasion is worthy of considerable profanity, but cuss low, cuss low!”[4]

Upon reaching the other side of the river, they surprised the enemy pickets. McCook continued his report:

They drove the enemy out of their rifle pits, captured a non-commissioned officer, three men and two boats on the other side. They would have got more, but the rebels had the advantage in running through the bushes with clothes on. It was certainly one of the funniest sights of the war, and a very successful raid for naked men to make.[5]

On July 16, 1864, Colonel Brownlow wrote to his father, who printed the letter in the July 29 issue of The Knoxville Tri-Weekly Whig and Rebel Ventilator, a militant anti-Confederate paper edited by William G. “Parson” Brownlow himself:

Last week we were detached to guard ‘Cochran’s Ford’, on the extreme right. The river here is very shallow, and we have to be on the alert night and day. I was glad to have the position, from the fact that it was a locality where no soldiers have ever been…. Directly opposite from us is a rebel post. The day before we were ordered to leave this post I ordered Capt. Moses Wiley, with two companies to strip themselves and be ready to cross and charge the enemy at the ford, whilst I would take a select detachment of men and swim the river four hundred yards above, for the purpose of capturing the rebel pickets. I selected the best swimmers in the regiment, put our guns in a canoe, and started over. As soon as Capt. Wiley saw that I had nearly reached the opposite shore, [he and his men] charged very bravely, but missing the ford, when half way over, he and every man went plunging in over their heads, and just then the rebels opened fire upon them, and compelled every man to seek shelter under the large rocks in the river, as best they could. Capt. Wiley was now in such a condition as to be unable to advance or retreat, and unfortunately left me and my ten men on the enemies[sic] side of the river, without help, and with a prospect of going to Atlanta sooner than we desired, destitute of even so much as a shirt. Not fancying this, and acting on the maxim that ‘he who never bets never wins’, I determined to charge upon the rear of the rebels, who were firing at Wiley’s party. My charge was a success, I completely surprised them and took them prisoner, and with them I captured a long ferry-boat, and returned to my command. The sergeant in command of the rebels was a New York Dentist, who told me that he had been living in the South for a short time. – He said he was never more surprised, and did not think any person was bold enough to swim in a river and attack them.[6]

One of the captured Confederates told his captors it was good they were successful, because if the Confederates had captured Brownlow’s Tennesseans, they would have been shot as spies because they were out of uniform.[7]

This expedition broke up the friendly communication which for several days had been established between the pickets across the river. The morning after the occurrence notice was given of the changed situation by a Reb yelling out across the stream:

“Hello, Yank!”

“What do you want, Johnny?”

“Can’t talk to you ‘uns any more!”

“How is that?”

“Orders to dry up!”

“What for, Johnny?”

“”Oh! JIM BROWNLOW, with his d—d Tennessee Yanks, swam over upon the left last night and stormed our rifle-pits naked – captured sixty of our boys and made ‘em swim back with him. We ‘uns have got to keep you ‘uns on your side of the river now.”[8]

General Sherman was said to have been amused with the story of Brownlow’s naked exploits and a ‘Special Artist’ for Harper’s Weekly prepared a sketch of his men charging across the Chattahoochee River with the bare necessities.

Brian Kowell is a past president of the Cleveland Civil War Round Table and has had an article published in America’s Civil War July 1992 edition about the Buckland Races.

[1] Scaife, William R., Chattahoochee River Line: An American Maginot.

[2] Scaife, William R., The Campaign for Atlanta, Saline. Michigan, McNaughton & Gunn, Inc. 1993. P. 80. Castel, Albert, Decision in the West: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864, Lawrence, Kansas, University of Kansas Press. 1992. Pp.334-335.

[3] Edward McCook’s Report, The War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880-1901. O. R. Series 1, Vol. 38, Part 2, p. 760.

[4] Belcher, Dennis W., The Cavalry of the Army of the Cumberland, Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland & Company,, Inc., Publishers, 2016. P.240. Carter, W.R., History of the First Regiment of Tennessee Volunteer Cavalry, Knoxville, Guant-Ogden Co., Printers and Binders, 1902. Pp.19-62

[5] O.R. Series 1, Vol. 38, Part 2, p. 760.

[6] Brownlow, J., “More on ‘Raw Courage’”, ed. Richard M. McMurry, Civil War Times Illustrated, Vol. XIV, No. 6, October 1975. Pp. 36-38

[7] Belcher, The Cavalry of the Army of the Cumberland, p. 240

[8] Brownlow, ed. McMurry, CWTI. P. 38.