“We Come Out of Kentucky Unsoiled by Her Slavery Principles:” Anti-Slavery Federals in the Bluegrass State – Part II

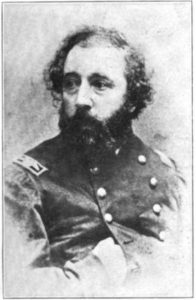

It may be because of the Atkins incidents, the increasing pressure by loyal slaveholding citizens, and a kerfuffle of their own with a prominent Kentucky justice, that the colonel and a couple of soldiers from the 22nd Wisconsin Infantry—also camped at Nicholasville—used a more surreptitious method to help a Black woman eager for freedom at about this same time.[1]

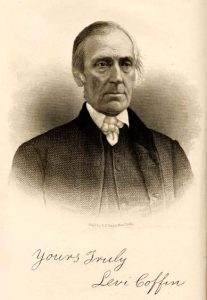

On or about November 10, 1862, “a young mulatto slave girl, about eighteen years old, of fine appearance, was sold by her master, for the sum of seventeen hundred dollars, to a man who designed placing her in a house of ill-fame at Lexington, Kentucky,” recalled famed Underground Railroad conductor Levi Coffin. It is unknown if this unnamed woman knew the 22nd Wisconsin’s reputation as the “Abolitionist Regiment,” or if she perhaps was just fortunate to come into their camp near Nicholasville. After she told her story to the soldiers, they determined to help her gain her freedom.[2]

Hiding her from her enslaver who came for her, Col. William Utley thought it best to get her out of Kentucky as soon as possible to avoid her possible recapture. Sgt. Jesse L. Berch and Corp. Frank M. Rockwell volunteered to take her to Cincinnati. One of the regiment’s officers knew Coffin lived there and could help her get further north. Berch and Rockwell had the mixed-race woman change into soldier’s clothes and hid her in a sutler’s wagon beneath a load of hay. The three made the 100-mile trip to the Queen City without any trouble. Once arriving at Coffin’s house, Mrs. Coffin helped the woman change. According to Coffin, she “transformed into a young lady of modest manners and pleasing appearance, who won the interest of all by her intelligence and amiable character.”[3]

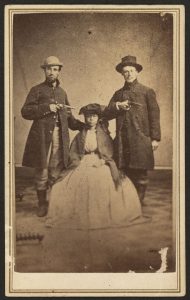

While in Cincinnati, the trio took an opportunity to have their photograph made at J. P. Ball’s Photographic Gallery on West Fourth Street. The image shows the formerly enslaved woman wearing a modest dress, shawl, and hat, seated between Corp. Rockwell and Sgt. Berch. Both soldiers hold pistols in their right hands as a show of protection for the woman. In addition, Berch and Rockwell telegraphed to friends in Racine, Wisconsin, to expect the woman soon. Coffin noted that “She was nicely dressed, and wore a veil, presenting the appearance of a white lady.” Doing so helped ensure that she had a first-class seat on her trip north. Coffin recalled that after her train pulled away Berch and Rockwell remarked that “it seemed one of the happiest moments of their lives when they saw her safely on her way to a place beyond the reach of her pursuers.”[4]

Berch wrote to Coffin on November 17, when he and Rockwell returned to their Nicholasville camp. Berch explained that “you would have rejoiced to hear the loud cheering and hearty welcome that greeted us on our arrival. Our long delay had occasioned many fears as to our welfare; but when they saw us approach, the burden of their anxiety was gone, and they welcomed us by one hearty outburst of cheers.”[5]

As to the destiny of the enslaved woman, whose name is lost to history, Coffin mentioned that he had recently (in 1876) heard from Birch, who informed Coffin of “her safe arrival in Racine, and her residence there for a few months.” Berch added that “Afterward she married a young barber and moved to Illinois” but Berch had “never been able to ascertain her whereabouts since” he left the army despite his and Rockwell’s repeated efforts to learn about her.[6]

The 22nd Wisconsin’s Kentucky troubles were not yet over. Moving to Danville for a little over a month, and then to Louisville to embark on steamboats to head downriver and eventually to Nashville, Tennessee, they continued to rile the local populations with their abolitionist sentiments and actions.

Chaplain C. D. Pillsbury wrote to the Weekly Racine Advocate on February 3, 1863, providing an update on their most recent happenings. The perceptive Pillsbury noted of Kentuckians that “On the subject of slavery, the people are very nearly united—almost to a unit. The leading men of the State and the most influential classes of the people are resolutely, almost madly determined to sustain the institution at all hazards.” Despite the Bluegrass State’s pro-slavery sentiment, Pillsbury noted that “The 22nd maintained her [anti-slavery] position unwaveringly, till she left the State. No contraband was taken from our ranks, nor give up at the demand of the slave-catcher.”[7]

Their record received a final testing at Louisville. Pillsbury claimed that enslavers who claimed human property within the regiment followed them to the wharf. “A citizen friend approached [Utley] and told him that he would have trouble in going through the city, and he said to him: ‘Don’t fire the first gun.’ ‘Fix bayonets!’ sounded along the line, and the order was promptly and cheerfully obeyed.” Pillsbury, walking in advance of the regiment and apparently not thought part of them, had a citizen ask him if the 22nd had already passed. He responded that it had not, and the man told him he had better watch out as “there will be music when it passes here.” The man responded that the citizens “took every niggerr from the regiments which have passed, and they declared that they would die rather than let the 22nd Wis. leave the state with a nigger with them.” Pillsbury told the man that if there is an attempt to take any away “there will be music.”[8]

One man came into the ranks and attempted to lay hands on a Black man who accompanied the regiment. “’Snap’ went the cap!” But, “Fortunate for Mr. Slave-catcher” the Black man’s pistol misfired. A dozen soldiers rushed with bayonets, one apparently sticking the man and “he came from the ranks at a greater velocity than he entered them.” No other reclamation attempts came, but the crowd, shook their fists and yelled threats as the 22nd made their way to the Ohio River wharf.[9]

When they got to the Commercial, the steamboat’s captain, “a Kentuckian,” attempted to prevent any African Americans from boarding. He claimed that he would be legally responsible if any left on his boat. Col. Utley informed him that his boat was in the employment of the government and as the commander of the troops aboard, Utley was ultimately in charge and ordered the captain “to steam up and make all necessary arrangements to move down the river.” However, before they embarked, the Jefferson County sheriff served Utley with a writ. The sheriff told Utley that he would drop the charges if Utley gave up the Black men on board. Utley “received the papers with becoming dignity” and merely gave the steamboat captain orders to head off. And away they went. Pillsbury closed his letter to the Advocate appropriately, noting, “We come out of Kentucky unsoiled by her slavery principles.”[10]

In many cases, the success or failure of emancipatory efforts in Kentucky relied on collaborative efforts. The instances shared above would not have been possible were it not for the agency expressed and the courage displayed by enslaved individuals in leaving behind their lives of bondage and pursuing freedom. However, their success rate may very well have been increased by the willingness of the Federal soldiers they came in contact with to help them. By not turning enslaved people back over to their enslavers, and using their enhanced power as soldiers in a time of war, created an alliance of liberty.

[1] For a two-part article on other anti-slavery actions by the 22nd Wisconsin that I previously wrote see: A Kentucky Conundrum: Lincoln, the Law, and Black Liberty – Part I & Part II.

[2] Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin, Western Tract Society, 1876, 606-607.

[3] Ibid, 607.

[4] Ibid, 608.

[5] Ibid, 608-609.

[6] Ibid, 609.

[7] Weekly Racine Advocate, February 3, 1863.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.