Gettysburg Off the Beaten Path: Arcadia and Prospect Hall

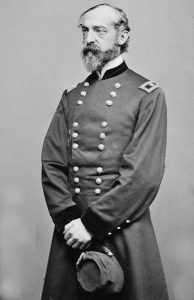

Major General George Gordon Meade settled into bed on the night of July 27, 1863 after a long day in the saddle. He and his V Corps of the Union Army of the Potomac had completed a hard march from northern Virginia to Frederick, Maryland. After ordering the men to bivouac along the banks of Ballenger Creek just south of the city, Meade briefly drifted off to sleep. But he was startled awake in the middle of the night by a strange man in strange clothes offering him command of the Army of the Potomac.[1]

Meade’s nighttime intrusion was the climax of an unfolding army drama. The defeat at the battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863 had permanently damaged President Abraham Lincoln’s faith in Union army commander Joseph Hooker. Therefore, Lincoln and his cabinet quietly sought a replacement in the wake of the Confederate incursion into Pennsylvania in June. As Rebel troops marched down the Shenandoah Valley, Hooker desired to relieve the Union garrison at Harpers Ferry, but General in Chief Henry Halleck countermanded his order. Perhaps seeking leverage in the situation, Hooker tendered his resignation. And Lincoln accepted it.[2]

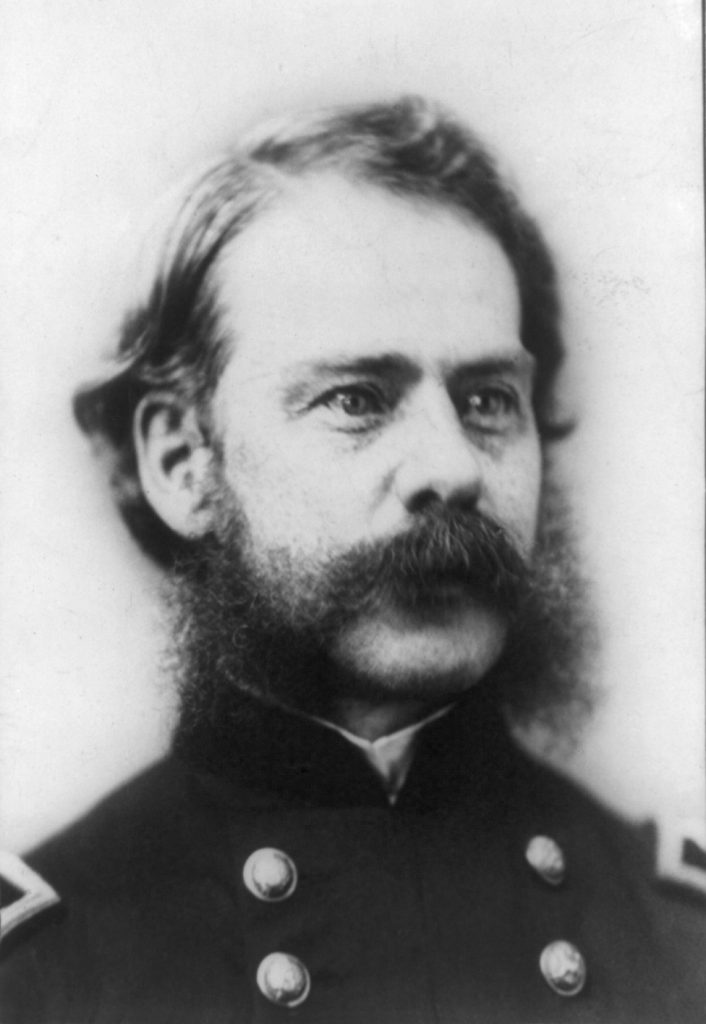

The War Department dispatched Colonel James A. Hardie of Halleck’s staff to relieve Hooker and pass command to Meade, a Philadelphia native. Lincoln believed Meade would “fight well on his own dunghill” as the Confederate army began moving into Pennsylvania.[3] Dressed in civilian clothes, Hardie stepped off a train in Frederick City at about midnight on June 28 and set out to find Meade’s headquarters.[4] The general was encamped on the grounds of “Arcadia,” a large home owned by Robert McGill situated along the Buckeystown Pike.[5] After procuring directions from several army officers, Hardie arrived at Arcadia at around 3:00 am. As he entered Meade’s tent, the colonel professed to be the bearer of trouble. “At first I thought it was either to relieve or arrest me,” Meade wrote to his wife the next day.[6] But his fears were quickly dispelled after reading Hardie’s written orders.[7] Though Meade had not schemed for army command like others had, he dutifully accepted it as a soldier should.[8]

After accepting Hardie’s orders, the general immediately went to work. He received briefings on the movements of both the Army of the Potomac and the enemy, issued orders to the seven infantry corps, and did practically all he could to understand the military situation.[9] At dawn, Meade and Hardie travelled four miles to Hooker’s headquarters at Prospect Hall mansion overlooking Frederick City. Hooker accepted Colonel Hardie’s orders with dignity, perhaps knowing that he had gambled his last chip and lost.[10] By that time, the general had alienated nearly every high-ranking officer in the Army of the Potomac.

By all accounts the transfer of command proceeded cordially. Only when Hooker revealed the strung-out nature of the Army of the Potomac did the “damned goggle-eyed snapping turtle” lose his cool, since Hooker had deliberately kept this knowledge from his subordinates. At first Meade desired to bring the seven corps back together to stage a grand review, which could allow him to become more familiar with his command. However, chief of staff Daniel Butterfield pointed out that this was neither necessary nor practical, given the present crisis.[11] When the meeting concluded, Meade emerged from the tent and looked to his son and aide-de-camp, George, Jr. “Well,” he said, “I am in command of the Army of the Potomac.”[12]

Both Arcadia and Prospect Hall still stand today. Built between 1790 and 1800, Arcadia served as the summer home of prominent Maryland attorney Arthur Shaaf. The mansion hosted several other Civil War officers in addition to George Gordon Meade. During the 1862 Maryland Campaign, Confederate Colonel William “Granny” Pendleton stayed at Arcadia, while Confederate General Jubal Early used the estate as a staging ground during the battle of Monocacy in 1864.

After the war, the mansion received numerous renovations and expansions, including the addition of a Queen Anne tower. However, the integrity of the original structure remains and currently serves as an Airbnb.[13] In March 2023, Frederick County issued a demolition permit for Arcadia, but two months later county executives issued orders to temporarily halt demolition of the mansion.[14]

Prospect Hall boasts an equally storied past. Built in 1803 by landowner David Dulaney, the mansion stands on the highest elevation in Frederick. George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette are counted among its earliest guests. It served as a Confederate hospital after the battle of Monocacy. In the twentieth century, the mansion fell to the ownership of U.S. Representative Joseph H. Himes then eventually the Saint John’s Catholic Prep school.

For more information on Prospect Hall, check out this video.

To Reach Prospect Hall:

From the town square.

- Proceed down York Street for 0.2 miles, then bear right onto the Hanover Road.

- Continue on the Hanover Road for 1.6 miles until you reach the junction of route US-15.

- Turn right to merge onto US-15 south and continue for 36 miles, following the signs for Frederick, MD.

- Take the US-15/US-340 West exit. Keep right and follow signs for MD route 180.

- At the traffic light, cross the Jefferson Pike and proceed down Himes Avenue.

- After driving to the bottom of the hill, turn left onto Mansion Drive. There, you will see a small monument and two Civil War Trails signs on the side of the road to your immediate right. Prospect Hall stands to your front left.

To Reach Arcadia:

From Prospect Hall.

- Turn your vehicle around and make a right back on Himes Avenue.

- At the traffic light, make a left on the Jefferson Pike. Follow the Jefferson Pike for approximately 1 mile.

- At the intersection with Crestwood Boulevard, make a left. Follow Crestwood Boulevard for about 2.5 miles.

- When you reach the intersection with the Buckeystown Pike, make a right.

- Continue for 1 mile, and Arcadia will appear on your right.

PLEASE NOTE THAT BOTH STRUCTURES ARE PRIVATE PROPERTY. PLEASE RESPECT THE OWNERS’ PRIVACY AND DO NOT KNOCK ON THE DOOR AND ASK THEM TO TOUR THE HOMES AND GROUNDS.

[1] Freeman Cleaves, Meade of Gettysburg (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960), 122-124.

[2] Cleaves, Meade of Gettysburg, 122.

[3] Scott L. Mingus Sr. and Eric J. Wittenberg, “If We Are Striking For Pennsylvania”: The Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Potomac March to Gettysburg, Volume 2: June 22-30, 1863 (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2023), 236.

[4] Cleaves, Meade of Gettysburg, 123.

[5] “Meade Receives Command of the Army of the Potomac: Gettysburg LBG Jim Hueting,” Gettysburg Daily, published October 13, 2009 (accessed January 13, 2023), https://www.gettysburgdaily.com/meade-receives-command-of-the-army-of-the-potomac-gettysburg-lbg-jim-hueting/.

[6] George Meade, The Life and Letters of George Gordon Meade, Major-General United States Army, vol. II, ed. George Gordon Meade, (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913), 11.

[7] Meade, The Life and Letters of George Gordon Meade, 11.

[8] Cleaves, Meade of Gettysburg, 123.

[9] Edwin B. Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968), 217.

[10] Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign, 217.

[11] Cleaves, Meade of Gettysburg, 125.

[12] Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign, 217.

[13] “Meade Receives Command of the Army of the Potomac: Gettysburg LBG Jim Hueting,” Gettysburg Daily, published October 13, 2009 (accessed January 13, 2023), https://www.gettysburgdaily.com/meade-receives-command-of-the-army-of-the-potomac-gettysburg-lbg-jim-hueting/.

[14] “Demolition permit for Arcadia mansion on hold,” Frederick News-Post, May 25, 2023.

In the first sentence I believe that it was in June of 1863 not July.

Good catch, Martin!

I’m not that familiar with the Frederick road network, but a footnote in Harry Pfanz’s “Gettysburg: The First Day” references a bronze plaque in a rock taken from Devil’s Den that was placed at the intersection of Ballenger Creek Road and Route 340, marking where Meade assumed command. Is this the same as the small monument close to Prospect Hall mentioned in the article?

Yes, the bronze plaque Pfanz is referring to is the same one I mention above. The stone monument (upon which the plaque is placed) was allegedly taken from Devil’s Den. A few wayside markers that detail Meade’s assumption of command accompany the monument as well.

Thanks for the article and the directions. It’s on my to do list.

I think you’ve got a mistake there in the first sentence. It was June of 1863, not July.

Otherwise a nice article about Frederick, MD, and the change of command. Goes well with yesterday’s book review of “Calamity at Frederick”.

The rebels invaded the North three times during the war, and each time came through Frederick. No wonder it’s now the home of the Museum of Civil War Medicine (well worth a visit).

Thanks for pointing out the mistake, and thanks for the praise. Frederick is definitely in the heart of “Civil War country”!

Thanks. I’ve made a few date and rank mistakes in my writing, too.

I’ve been enjoying the Frederick MD area since my daughter and her family moved to farm nearby, in Boonesboro. We’re always looking for a reason to go there. There’s Civil War in every direction! Just so happens I’m currently enjoying “If We Are Striking for Pennsylvania”, which you refer to. I traded books at a recent CW event with the author Scott Mingus. He got my “The Greatest Escape, a True American Civil War Adventure”.

Anyway, I’m going to try and take a look at those two mansions you wrote about next time I’m there. There’s always more to see. I live in Los Angeles, where all we have is one building!

Douglas Miller – I lived in Los Angeles and I don’t remember anything worth seeing east of the ocean, except maybe Tito’s..To what building are you referring?

Didn’t Washington die in 1799? How could he have visited prospect hall, built in 1803?

Correct, although I believe he visited the structure that preceded Prospect Hall’s construction in 1803.