Confederate cat kills a Maine soldier

Adapted from a Maine at War post published on March 6, 2024

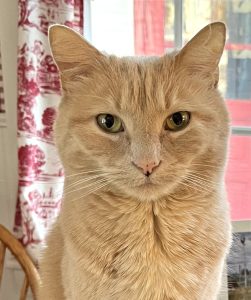

The last Confederate that Corp. Nahum H. Hall ever thought could kill him was an angry tabby, likely Sgt. Puss N. Boots, First Florida Feline Regiment.

Hall, a resident of Rockland on the Midcoast, was 33 when he enlisted as a private in Co. G, 28th Maine Infantry Regiment, a nine-month regiment that mustered at Camp E. D. Keyes in Augusta. A self-employed trader, he stood 5-11 and had gray eyes, dark hair, and a dark complexion. According to the 1860 U.S. Census for Rockland, Hall and his wife, Lydia, had a 7-year-old daughter, Sarah.

Hall enlisted in September 10, 1862 and mustered on October 10. The 28th Maine left Augusta by train on October 25, camped in East New York, and reached Louisiana in late January 1863. Shifted around the Department of the South, the regiment helped guard Pensacola from February 15 until leaving for New Orleans on March 24.

The 28th Mainers came to Pensacola to help protect it against a rumored Confederate assault. The trouble was, the Confederates were already there. “A good many cats infested the camps,” reported a Maine newspaper. The cats did so because rats and mice infested the camps, too.

These Confederate cats belonged to the First Florida Feline Regiment, many cat tails strong and multiplying almost daily. Realizing the threat that these purr-fidious Johnnies presented, the Yankee boys responded by “pursuing a war of extermination against them.”

Soldiers pursued a female cat that came “dashing into the tent in which Mr. Hall was,” the paper reported. A soldier grabbed the cat “by the legs or body,” and Hall “grasped her by the neck to prevent her from biting his comrade.” The angry, hissing, and flailing Confederate feline bit Hall’s right wrist. The intrepid Rockland cat catcher “was also bitten slightly in the flesh of his left hand.” What happened to the prisoner was not recorded.

Hall apparently pulled out a knife; we can assume so because “he cut out the flesh on the spot and applied tobacco as an antidote.” He was “apprehensive” that he might have gotten something worse than an infection, however, perhaps “some evil result.” Hall “entertained, even since the occurrence, an apprehension that this would cause his death,” a paper noted.

Hall and the 28th Maine returned to Augusta in August 1863. He immediately hied home to Lydia — and he “came home in very good health,” a Rockland newspaper noted. He was mustered out and honorably discharged on August 31.

On Tuesday, September 1, Hall “began to experience a pain in the knee, and subsequently was attacked with acute pains in the left arm which extended to the back and head.” A physician, Dr. John Esten, “was called on Wednesday, who pronounced the case to be inflammatory rheumatism, of which it had all all the symptoms, and administered the usual remedies. Relief was experienced from the treatment, and the patient continued to improve until Friday evening [September 4], when he was much better.”

But Hall thought the cat bite was affecting him. “He became impressed with the idea that he was attacked with hydrophobia,” a paper noted. Hydrophobia was the 19th-century term for rabies. “Dr. Esten, of course, endeavored to dispossess his patient of this impression, knowing that this, of itself, might produce injurious consequences, in his [Hall’s] extremely nervous condition.” Esten left Hall with “a nervine” on Friday evening, September 4, “but it not having the desired sedative effect, Mr. Hall repeated the dose until he had taken six times the usual quantity.”

Esten visited Hall Saturday morning and “found him exhibiting the symptoms of hydrophobia—a great dread of water, spasmodic nervous action and extreme salivation,” the paper reported.

According to Dictionary.com, “hydrophobia” is “an extreme dread or fear of water, especially when associated with painful involuntary throat spasms from a rabies infection.” That Saturday, Hall “could not bear the approach of water or any liquid, which he said produced sensations like those of drowning.” No evidence exists that Hall had almost drowned in the past, but those who survive a near drowning can appreciate his terror.

“To test these symptoms water was procured, which threw him [Hall] into nervous spasms,” the paper reported. Esten attempted “to calm his patient and sought to prevent him from dwelling on the idea of hydrophobia, representing that the over-dose of the medicine would produce the nervous action …

“But the hydrophobic symptoms continued to increase” on Saturday, and Esten and Hall’s friends realized “that the patient’s apprehensions were correct.” We can only imagine the horror that Lydia Hall was experiencing. Doctor Joel Richardson arrived at the house, examined Hall, and confirmed “the case to be hydrophobia.”

“Mr. Hall was rational and conscious of his condition through the last day of his illness, until 9 o’clock P.M., when he became insensible and continued to sink until about 2 o’clock on Sunday morning [September 6], when he died without a struggle.” Lydia Hall buried her husband in the Achorn Cemetery in Rockland on Monday, September 7. “His funeral … was attended by a large number of his friends and fellow-citizens,” a paper reported. The body was “attended to the grave by the Dirigo Engine Company and members of the Masonic fraternity.”

Did Nahum H. Hall die of hydrophobia (rabies) some six months after being bitten by that Confederate cat? According to the World Health Organization, the symptoms of rabies usually appear in two to three months, but can appear any time from a week to up to a year. It’s very possible that Hall was killed by Sgt. Puss N. Boots.

Sources: Death of Mr. N. J. Hall, Rockland Gazette, Saturday, September 12, 1863; Death from the Bite of a Cat, Daily Whig & Courier, Monday, September 21, 1863; 1860 U.S. Census for Rockland; Nahum H. Hall Soldier’s File, Maine State Archives; Whitman, William W. S., Maine in the War for the Union: A History of the Part Born by Maine Troops, Nelson Dingley Jr. & Co., Lewiston, ME, 1865, pp. 542-543

Excellent story. But you left out the part in which, for his valiant conduct in infiltrating the Union camp, the rebel cat was awarded the Confederate Congressional Meow of Honor.

My southern born wife had an unconstructed Confederate cat … he was a gray coated, raggedy looking barn cat and she named him Rebel, of course … without provocation, he would attack me and the other Yankees in the house … fortunately, he inflicted no mortal wounds like poor Corporal Hall.