A Witness to Pea Ridge

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome guest author Nate Pedersen. Nate is manager of the Archival and Reference Team at the Georgia Historical Society.

I collect old photo postcards of historic, or witness, trees. When this postcard of a black walnut tree (Juglans nigra) at Pea Ridge, Arkansas popped up on eBay, I was excited to buy it as it depicted a tree with Civil War provenance that I had never seen before. Like many readers and contributors to this site, I also couldn’t resist the opportunity to do a bit of Civil War research to learn more about the tree.

The internet, however, had nothing to say about this walnut tree, which bore witness to the 1862 battle. I thought it was an interesting coincidence that this Pea Ridge photo, at the site of a pivotal Confederate defeat, depicted a black walnut tree as Southerners used walnut hulls from such trees to produce the brown-black dye used in homespun clothes and some Confederate uniforms.

The caption on the postcard includes the intriguing statement that the tree is “battle scarred.” (Note: the hexagonal shape seen on the tree appears to be a sign, not some sort of shockingly well-centered cannon damage that the tree somehow survived). We’re left to trust the photographer’s caption on the postcard, even though we can’t see that damage ourselves. Presumably it contained numerous bullet holes.

On the far-right hand side of the image, you can the chimney of a building. My guess is this building is Elkhorn Tavern itself, a site that was held, for a night anyway, by Confederate General Earl Van Dorn and his 16,000-man Army of the West on March 7, 1862. After being pushed out of Missouri into northwestern Arkansas, Van Dorn intended to attack the US position at Pea Ridge. Sending his supply trains far to the rear, Van Dorn hoped to move quickly on the US position, but Gen. Samuel R. Curtis learned of the Confederate movements and countered by sending 10,000 men from the Army of the Southwest to intercept the Confederate advance.

On March 7, 1862, the armies collided at Elkhorn Tavern in fierce fighting that left two Confederate Brigadier Generals dead on the field. Nevertheless, the Confederates were able to hold Elkhorn Tavern for the night. Curtis, however, consolidated his forces and on March 8 he counterattacked the Confederate position, leading with heavy artillery fire. Van Dorn held a strong position but could not obtain additional supplies as he had previously ordered his supply trains far to the rear, and his troops were forced to retreat as they ran out of ammunition. Van Dorn had to eventually abandon the battlefield, leaving it – and by extension the border state of Missouri – in the hands of US troops for the remainder of the war.

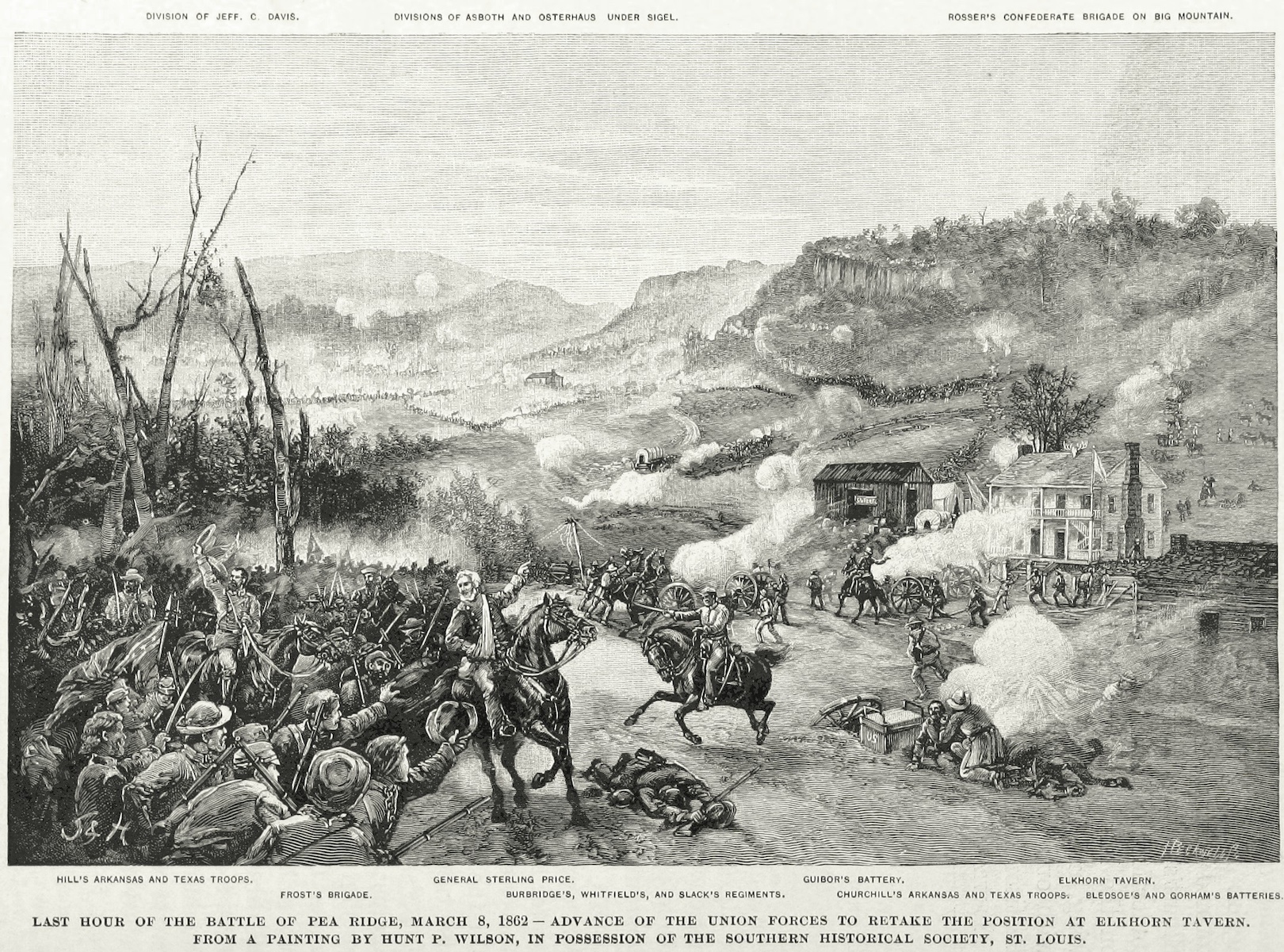

The fierce and pivotal fighting was all witnessed by this walnut tree. In researching historical images of Pea Ridge, I came across this depiction of the battle, which does, indeed, depict a large tree to the left of Elkhorn Tavern itself.

Could this be the same walnut tree seen in my photo postcard? It’s an intriguing possibility. Regardless, this battle-scarred witness tree is a haunting reminder of a major battle in the Trans-Mississippi theater.

Thanks to Nate Pedersen for introducing the story of the Black Walnut Tree.

I had the good fortune to visit Pea Ridge NMP a few years ago and found it to be one of the most complete and pristine battlefields in America. And further research confirmed that “driving the Rebels out of Southwest Missouri” is the reason why Pea Ridge was fought… in Arkansas. And there is more to the story of Pea Ridge (called Battle of Elkhorn Tavern by the Confederates…)

Following on Union victories at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, the Rebels abandoned the Gibraltar of the West (Columbus Kentucky). Major General Henry Halleck, commander of the Department of Missouri who authorized the operations against Henry and Donelson, and benefited from Fort Columbus falling into his lap, was elevated to command of the Department of the Mississippi, effective 11 March 1862. News of the victory at Pea Ridge back East in Washington only acted to justify Halleck’s promotion.

Upon his arrival in the Western Theatre, Henry Halleck established four goals: 1) secure his base; 2) drive the Rebels out of Missouri; 3) open the Mississippi River from the north; and 4) defeat the Rebels in the West in one crushing blow in southern Tennessee/ northern Mississippi. Halleck’s predecessor, John Fremont, went a long way towards “securing the base at St. Louis.” Halleck completed the job. Next, finding Fort Columbus too strong to be attacked directly, Halleck authorized operations to the east, up the Tennessee River, that “turned” Fort Columbus. With Samuel Curtis’s operation to drive the Rebels out of southwest Missouri underway, Halleck sent John Pope and his Army of the Mississippi southeast, through a 40-mile swamp, to threaten New Madrid from the rear. Flag-Officer Foote and his gunboats, mortars and observation balloon attacked Island No.10 from the north. Meanwhile, U.S. Grant was amassing an Army at Pittsburg Landing that would be put to use AFTER the capitulation of Island No.10; and Henry Halleck would personally lead that rebellion-ending Army. Major General Grant benefited from the Victory at Pea Ridge: troops no longer needed by Samuel Curtis to help drive Rebels out of Missouri were sent to Grant, instead.

Such was the plan, with three out of four goals accomplished.

When I visited Pea Ridge NMP all those years ago, I do not recall the Rangers mentioning the Black Walnut Tree at all. Thanks again for filling one of the gaps in my Civil War knowledge.

All the best

Mike Maxwell

Thanks, Mike, I’m glad you enjoyed the post. Appreciate your additions to the story.

I like these postcard posts. Please write more! I have started a new collection of old postcards with pictures of Confederate monuments since torn down.

Thanks, Katy, I’m glad you enjoyed the post. I am planning out a few more in this series.