Alex Garland’s Civil War and the Actual American Civil War

What does Alex Garland’s new movie, Civil War, have to do with the actual American Civil War?

Well, at first glance, not a whole lot.

Sure, if you squint a little, the rapid collapse of one side’s forces at the end has parallels to the Confederacy around Richmond in April 1865. The low-intensity, quasi-irregular warfare seen through most of the movie is reminiscent of the partisan and guerrilla warfare of the 1860s, particularly in the Western and Trans-Mississippi theaters.

But the new movie is intentionally vague on the root causes and political situation that have led the country into a second devastating civil war. The occasional turn of phrase by the president, offhand reference, or stylistic choice might feel familiar to today’s politics and help the film feel realistic, but there’s no easy parallel between the opposing forces in Civil War and the fault lines in the politics of the 2020s, or for that matter the 1860s.

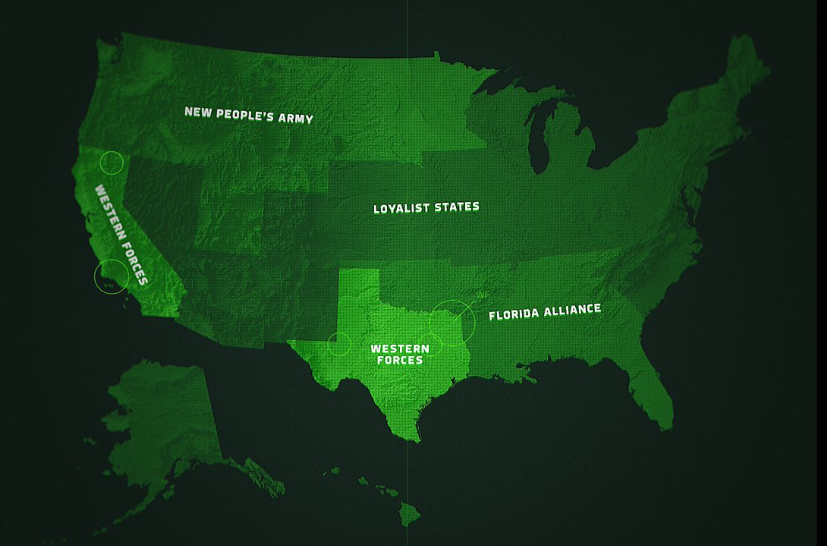

Instead, the movie paints a picture of a war that is largely devoid of ideology. That’s perhaps made clearest by the map of which states have seceded and joined various factions: Such politically disparate states as South Carolina, Vermont, Nebraska, and Massachusetts have stayed “loyal” to the federal government in D.C.

The loyalists are fighting at least two secessionist factions; the one featured most prominently in the movie is the “Western Forces,” led by the absurdly unlikely bedfellows of California and Texas. Another is led by Florida, and some of the movie’s publicity materials also show a fourth faction stretching all the way from Portland and Seattle to Minnesota.

From the decision to have more than two opposing sides, to the particular states chosen, there is clearly an intentional decision to steer the movie away from today’s red/blue, left/right, two-party fault lines. We’re usually taught the Civil War shorthanded as North vs South. Emerging Civil War readers know that already oversimplifies a story in which some Southern states never seceded, many White Southerners stayed loyal to the federal government, Black Southerners fought against the Confederacy for their freedom, and the occasional Northerner fought for the Confederacy. We can easily take for granted that the Civil War ended up being primarily a question of whether the United States would continue as one nation, or split into two.

But some of the most interesting and understudied stories of the Civil War era are the numerous movements to carve up individual states, or to break additional regions off to form their own countries.

There was a great deal of speculation, especially early in the War, that secession wouldn’t stop with the Confederacy. A sitting (albeit nonvoting) member of Congress from the New Mexico Territory advocated in the Santa Fe Gazette for joining a theoretical Pacific Republic.[1] In the wake of Lincoln’s election, prominent Californians agreed that they should consider going their own way, and perhaps bringing a sizeable chunk of the West with them.[2]

Debate also raged over whether the Midwest should secede in order to regain access to the Mississippi River, an import outlet for exporting the crops that the region’s economy depended on. The idea gained enough traction to be debated in the Confederate Congress, and the political vulnerability of this region certainly helped inform how much Lincoln prioritized reopening the “Father of Waters” to commercial traffic.[3] Even prominent New Yorkers seriously considered seceding from both the state and the country, in order to become an independent city-state maintaining lucrative commercial ties with all sides.[4]

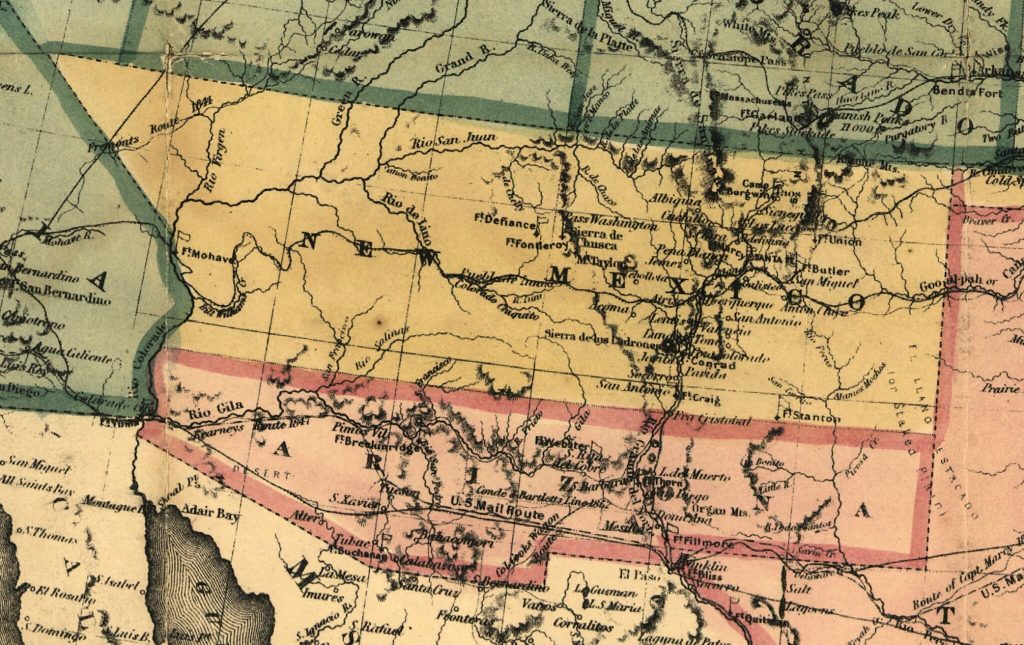

Even with states and territories, boundaries were fiercely contested. Before the Civil War, Texas sought to extend its western border to the banks of the Rio Grande in modern-day New Mexico. That included launching failed campaigns to occupy Santa Fe, a prequel to Sibley’s 1862 invasion of the territory.[5] That campaign was inspired in part by the residents of the southern half of the New Mexico Territory declaring in 1861 that they were, in fact, now the Arizona Territory and seeking to join the Confederacy. Southern transplants to California also sought to split off the southern half of the Golden State to found a new, pro-slavery state, which would have been called Colorado (no relation to today’s state by the same name).[6]

Further east, Unionists in Confederate states expressed their dissatisfaction with secession by declaring their own states. A 2016 movie starring Matthew McConaughey brought renewed interest in the so-called Free State of Jones in Mississippi. Most famously, West Virginia became its own state after effectively seceding from Confederate Virginia.

So to return to our original question: What does the new movie, Civil War, have to do with the actual Civil War? While it steers clear of any overt politics, it vividly portrays the complexity of any civil war – both politically, and for individual participants – that transcends neat, clean lines on a map and simple narratives in history books. If nothing else, that will resonate for students of the American Civil War.

[1] Miguel Otero. Santa Fe Gazette. December 8, 1860.

[2] Richard Kreitner. Break It Up: Secession, Division and the Secret History of America’s Imperfect Union. Little, Brown and Company, 2020, 257-259.

[3] Neil Chatelain. Treasure and Empire in the Civil War: The Panama Route, the West and the Campaign to Control America’s Mineral Wealth. McFarland, 2024, 50-52.

[4] Richard Kreitner. Break It Up: Secession, Division and the Secret History of America’s Imperfect Union. Little, Brown and Company, 2020, 261-265

[5] Stephen G. Hyslop. Building a House Divided: Slavery, Westward Expansion, and the Roots of the Civil War. University of Oklahoma Press, 2023, 210-214.

[6] Kevin Waite. West of Slavery: The Southern Dream of a Transcontinental Empire. University of North Carolina Press, 2021, 156-157.

I’m so glad someone wrote about this! I watched a review of the movie, which got me thinking about the parallels, as well. If I’m not mistaken, both wars end with a presidential assassination too?

Thanks Evan! That’s true, though boy are they very different flavors of that.

We watched the movie yesterday and it was a very good movie from a neutral viewpoint, will definitely see it again!