USS Monitor: The Half-Charge Myth

Many published descriptions of the battle of Hampton Roads (including my recent book[1]) explain that USS Monitor expended only “half charges” of powder in her 11-inch Dahlgren guns during that legendary fight with CSS Virginia on March 9, 1862. Hindsight then and since spawned several engaging “what ifs” (see previous post), one of which holds that, had Monitor used “full charges,” Virginia’s armor might have been penetrated and her menacing threat neutralized. But that’s not quite what happened.

A recent episode of an excellent naval history YouTube channel[2] corrected the record for me. As is well known, neither warship suffered serious injury. Monitor sustained a few dents in her turret, gouges in the deck, and damage to the pilot house while Virginia’s external equipment and boats were demolished, her smokestack perforated, and a few surface iron plates blown away without compromising the armored casemate. For two more months, the Rebel ironclad disrupted Union operations in and around Hampton Roads including McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign.

Were Monitor’s cannons capable of breaching Virginia’s armor and only prevented from doing so by the overly cautious usage of half charges? Was this ordered by higher ups or just hesitance on the part of the ship’s commander, Lieutenant John Worden? What did happen and how did the half-charge myth originate?

For clarification, we return to February 1844 during a Potomac River VIP cruise aboard the brand-new USS Princeton. A proud U.S. Navy was showing off its first propeller-driven, steam warship to President John Tyler and a party of dignitaries. Swedish engineer John Ericsson designed the ship and supervised its construction; he would subsequently invent Monitor.

Ericsson also designed one of Princeton’s two big guns and directed its manufacture by Mersey Iron Works in Liverpool, England. An exemplar of the dramatic revolution in naval artillery, his design used “built-up construction.” Red-hot iron bands mounted around the breech shrank when cooled, pre-tensioning the tube, greatly increasing the charge it could contain and therefore the range and power of the gun. Named the “Oregon gun,” the smooth bore muzzleloader could project 12-inch, 225-pound shot five miles using a 50-pound powder charge. It was test fired more than 150 times.

Captain Robert F. Stockton, USN, was Princeton’s primary sponsor and commanding officer. He had lured Ericsson over from England for the job of engineer in charge. Stockton also designed and directed construction of the “Peacemaker,” another 12-inch muzzleloader, by Hogg and DeLamater of New York City. But American forging technology was not as advanced as Great Britain’s and the gun was hurriedly manufactured by a different technique: Reinforcing bands were welded on rather than heat shrinked. It was not extensively tested, by one account having been fired only five times.

To the delight of 400 onlookers aboard Princeton that February day in 1844, the Peacemaker’s boom echoed three times over the Potomac. Stockton called for another demonstration as a salute to George Washington’s estate at Mount Vernon. Upon detonation, the breech burst, blasting hot chunks of iron about the deck, killing six—including the secretaries of state and navy—and wounding more than a dozen. President Tyler was below decks and uninjured. The influential Captain Stockton publicly shifted blame for Peacemaker’s failure to Ericsson although he had no role in its construction.

Exploding barrels were an occupational hazard during the technological arms race underway in Europe and America as naval artillery became ever bigger and more powerful. The Princeton disaster prompted reexamination of manufacturing processes leading to new techniques such as systems pioneered by Thomas Rodman and John A. Dahlgren.

Rapid progress in metallurgy, forging processes, and ballistics produced stronger and more structurally sound cannons, but was more a matter of trial and error by enthusiastic tinkerers than by scientific understanding or controlled experimentation. Following routine testing procedures, the designer would determine the standard “service charge” of a new weapon by calculating the amount of powder he thought could be stuffed down the barrel based on experience and then firing the gun to see if he was right.

In 1879, another gun under testing failed catastrophically in the presence of 40-year-old Lieutenant John Dahlgren, ordnance expert and founder of the U.S. Navy Ordnance Department at the Washington Navy Yard. Considering the history of failures, the navy adopted a more conservative testing regimen beginning with a small charge and incrementally increasing it through multiple firings until satisfactory performance was achieved without failure.

Dahlgren determined to design an innovative weapon capable of firing both shot and shell, and that was safe. Rather than installing reinforcing bands, he forged the barrel with significantly greater thickness around the firing chamber to contain increased pressures resulting in a distinctive “soda bottle” shape.

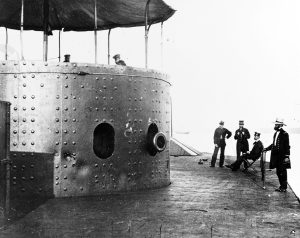

Dahlgren’s 9-inch gun became the standard naval artillery piece; Virginia mounted six of them confiscated from USS Merrimack. Monitor was armed with two 11-inch Dahlgrens, then the most potent weapon in service although later monitor-class vessels would carry 15-inchers.

Dahlgren enforced an exacting testing program with hundreds of firings of multiple combinations of powder, shot, and shell. (No Dahlgren gun burst during service, a notable distinction for the time.) By 1862, the 11-inch guns had been in service for less than a half decade. Results to date had verified acceptable and safe performance employing charges up to 15 pounds, and so that is what he recommended.

Monitor’s gunners employed 15-pound service charges to launch 187-pound solid shot at Virginia because that is what their gunnery manuals and training prescribed. Twenty men confronted their first combat among two gargantuan guns jammed into a claustrophobic, rotating, 20×9-foot iron drum that no one had ever seen. Increasing the powder charge was not considered; it could have been more catastrophic than the Princeton incident.

How did the “half charge” myth originate? Post-battle reflection was intense on both sides causing controversy ever since. The future would witness brisk seesaw advances between more powerful naval armament and more protective armor. Then-Commander (and soon-to-be Captain) John Dahlgren was as disappointed as anyone about the indecisive engagement. Appointed to command the Washington Navy Yard, he would become a close friend and confidante of the president, who often escaped the Executive Mansion to visit him.

The Confederate navy had just demonstrated an iron-armored warship that could successfully resist their best gun; they were rapidly constructing more such monsters from the North Carolina Sounds to New Orleans and Memphis. Dahlgren’s 15-inch cannon was still in development. The still-wooden U.S. Navy was in serious trouble.

Dahlgren initiated a careful testing program to improve the range and power of the 11-incher. New forms of higher energy powder were still experimental; he could try new forms of shot such as steel bolts, but the technology to mass produce reliable quality steel shot was a few years off.

So, the ordnance chief simply increased the amount of powder incrementally and kept firing a few hundred rounds at each step, again a process of trial and error, but it advanced rapidly. Soon a 20-pound service charge was deemed safe, then revised steadily upward to 25 pounds by war’s end. A 30-pound charge was authorized for guns in good condition.

The observation was easily made that—retrospectively—the barrel was capable of containing much higher chamber pressures than originally understood. “Full charges” of 30 pounds could have been used in March 1862; therefore, the 15 pounds actually applied represented a “half charge.” As it often does, history became muddled. The assumption that someone had made a conscious decision to use half charges against Virginia dominates the narrative today. This is an excellent example of the need for careful, detailed historical research as well as for correcting the record when necessary.

It turns out that neither ironclad at Hampton Roads was especially well equipped to deal with the other. Dahlgren’s guns—designed in the early 1850’s—were larger and more powerful than standard weapons of the period and, importantly, capable of disgorging both shot and shell. However, they employed somewhat lower muzzle velocity. A relatively slow projectile with a large surface area had good smashing power against wooden hulls, but unless propelled by a huge powder charge, little ability to breach Virginia’s two layers of 2-inch iron armor backed by 2 feet of oak and pine.

It turns out that neither ironclad at Hampton Roads was especially well equipped to deal with the other. Dahlgren’s guns—designed in the early 1850’s—were larger and more powerful than standard weapons of the period and, importantly, capable of disgorging both shot and shell. However, they employed somewhat lower muzzle velocity. A relatively slow projectile with a large surface area had good smashing power against wooden hulls, but unless propelled by a huge powder charge, little ability to breach Virginia’s two layers of 2-inch iron armor backed by 2 feet of oak and pine.

Virginia’s commander, Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones, reported that most of Monitor’s hits were oblique, caroming off the inclined surface, cracking or sometimes blowing away large chunks of the external plate layer. A few missiles connecting at right angles cracked but did not penetrate the wood backing. However, in several instances, two or more adjacent blows displaced additional iron and bulged the wood inside. “Generally the shot were much scattered. . . . The shield was never pierced though it was evident that two shots striking in the same place would have made a large hole through everything.”[3]

Virginia Lieutenant John Taylor Wood agreed: “Had the fire been concentrated on any one spot, the shield would have been pierced; or had larger charges been used, the result would have been the same.” [4] Monitor’s chief engineer found fault with their ammunition: 11-inch solid cast-iron round shot. The difficulty was “want of homogeneity” (irregularities in roundness or “windage”) causing them “to go almost anywhere except where the gun was aimed.”[5]

Conversely, Virginia had been loaded that day with thin-walled explosive shells perfect for violently deconstructing the flammable, fragile wooden vessels she expected to encounter. However, upon impact with an iron surface, shells would either smash open causing a dramatic but low-order flash, or explode at the surface dissipating most energy uselessly into open air. Solid shot had more concentrated smashing power, but only a few rounds had been supplied for the hot-shot guns (the 9-inch Dahlgrens that had immolated USS Congress the day before), and they were quickly expended making a few dents in Monitor’s turret.

Besides the six 9-inch Dahlgrens, Virginia mounted four innovative and highly regarded naval rifles designed by Rebel ordnance expert Lieutenant John M. Brooke, also designer of the Confederate ironclad. Brooke had been testing armor-piercing steel bolts—elongated cylinders with blunt ends—using a test target based on Northern newspaper drawings of Monitor’s turret, but the bolts were not yet available. Confederates would claim that solid shot and/or bolts would have disabled or destroyed the Union ironclad, another contentious “what if.”

On March 9, 1862, USS Monitor gunners used full charges as then prescribed against their opponent. Only later was it discovered that they might have doubled the charges for more decisive results. Now you know.

On March 9, 1862, USS Monitor gunners used full charges as then prescribed against their opponent. Only later was it discovered that they might have doubled the charges for more decisive results. Now you know.

[1] Dwight Sturtevant Hughes, Unlike Anything That Ever Floated: The Monitor and Virginia and the Battle of Hampton Roads, March 8-9, 1862 (Savas Beatie, 2021).

[2] https://www.youtube.com/@Drachinifel, John Dahlgren and the Half Charge Myth.

[3] Catesby ap Roger Jones, “Services of the Virginia,” in Southern Historical Society Papers, 52 vols, vol. 11, 72.

[4] John Taylor Wood, “The First Fight of Iron-Clads,” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, 4 vols. (New York, 1884-1888), vol. 1, 703.

[5] Stimers to Smith, March 9, 1862, in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 2 series, 29 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1894-1922), series 1, vol. 7, 27-28.

Thanks for the article. As a retired engineering duty officer it’s always interesting to read of the history of the profession.

thanks for this essay Dwight … great insights into the importance of gunnery and carrying the right ordnance … i always wondered why concentrated fire from VIRGINIA didn’t do more damage to MONITOR’s gun turret — now I know!

Couldn’t stop reading. Thanks

It should be noted no 11 inch solid shot ever pierced 4inches of armor plate in any battle!!