“Willing to be Useful to his Country;” Robert Q. Shirley of Vicksburg, Mississippi

ECW welcomes back guest author Jeff T. Giambrone

In October 1864, Adeline Shirley of Vicksburg, Mississippi, wrote a letter to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, commander of all the Union armies. In this missive she presumed to ask the general for a favor. Grant probably received numerous such entreaties, but in this case he decided to grant Adeline’s request. He may have felt he owed her, because in the spring of 1863 the Union army had literally brought the war to the Shirley family’s front doorstep.

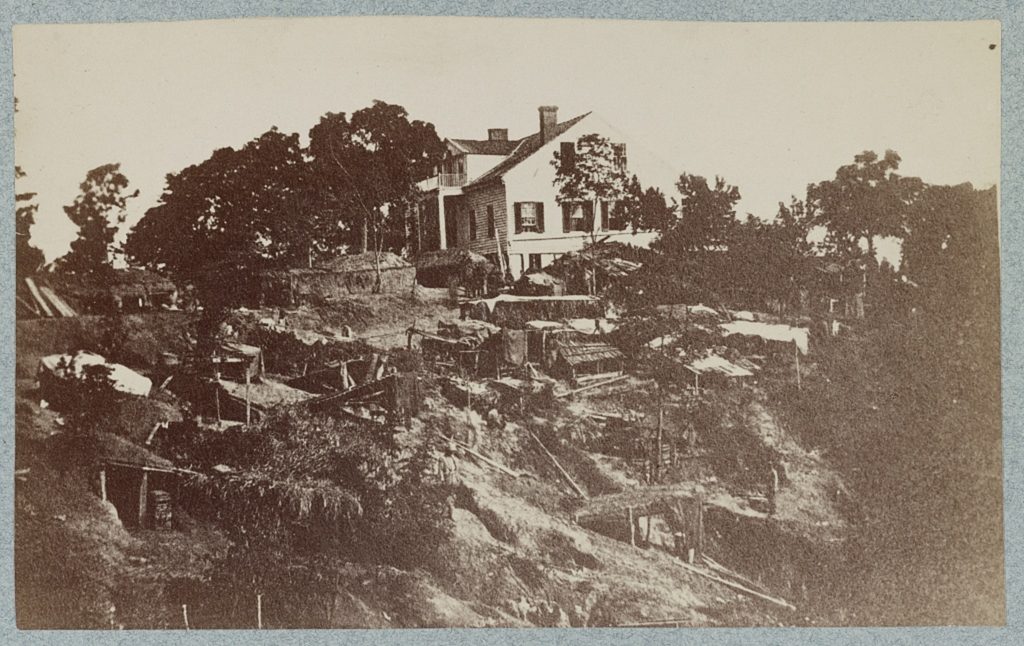

The Shirley’s home, known during the siege of Vicksburg as the “White House,” is the only wartime structure still standing today in the Vicksburg National Military Park. It was purchased by James and Adeline Shirley in January 1851; it had been described in a local newspaper as “a most desirable residence in a healthy location.”[1] By the spring of 1863, the “White House” was in a most decidedly unhealthy location; one writer noted:

“Upon visiting it I found it to be a typical Southern homestead, a story and a half high, a wide hall in the centre, with large, high-ceiled rooms on each side and spacious verandas back and front. It stood about three hundred yards in front of the Confederate defenses. The bullets of the enemy had perforated the house here and there, and the outbuildings and fences were all destroyed.”[2]

Both James and Adeline Shirley were originally from the north: James was born in New Hampshire and Adeline in Massachusetts.[3] Their pro-Union views were not popular in Vicksburg, and they had passed on these sympathies to their children.[4] Even before the war started the Shirleys’ eldest son, Frederick, managed to land himself in hot water with his outspoken commentary on politics. His sister Alice later wrote of the incident that got him in trouble:

“While there were mutterings of war, my brother Frederick, then a member of a Vicksburg military company, was unwise enough to say that he would rather serve Lincoln twenty years than Jeff Davis two hours. This inflamed the hot-headed young Southerners, and there was loud talk of hanging…After a short family conference, we packed his trunk, and in the early morning he left for Indiana, and only once did we hear from him until he returned after the surrender of Vicksburg.”[5]

When the Union Army began its 1863 Vicksburg campaign, Alice Shirley was at school in Clinton, Mississippi, about 34 miles east of Vicksburg. Fearing for her safety, James Shirley went to collect his daughter, but the arrival of the Union army in Clinton trapped them both in the town for a time. This left Adeline and Robert at home with just the family servants when the Federal troops arrived on May 18 and the fighting began in earnest. Alice Shirley wrote of this time:

“My mother and brother had remained for three days at our home after the siege begun. She told me that she and the two house servants sat most of the time in the chimney corner where the bullets might not strike them. Meanwhile, our carriage driver and others of our colored men were digging a cave in the side of a hill in the valley some distance back of the house.”[6]

While Adeline and her servants sheltered from the storm of war taking place around them, Robert Q. Shirley was not content to stand back and let others do all the fighting. He wanted to take an active role against the Confederates in Vicksburg. His sister Alice recorded:

“My brother was delighted to be permitted to go into the trenches and do a little fighting for his country, but those three days must have been a time of great distress for my mother, and I think she never entirely recovered from the severe strain caused by the war.”[7]

After ensuring the safety of his daughter Alice in Clinton, James Shirley was anxious to return to his wife and son in Vicksburg, for by that time the Union army had besieged the city and he was desperate to get them out of the line of fire. All other modes of transportation being unavailable, there was no choice for James but to walk to Vicksburg. Alice wrote of her father’s journey:

“So we saw him start out on that long, hot, dusty walk of forty miles, – not a young man, or accustomed to much walking. It was a sad parting, for we thought it might be a last good-bye.”[8]

James Shirley was able to make the journey, and he was able to get his family to safer accommodations outside Vicksburg. But the strain of the war was too much for him, and he died on August 9, 1863, shortly after the siege ended. [9]

With the fighting at Vicksburg over, Adeline had to decide what was best for her children. For Robert this meant shipping him to her husband’s home state of New Hampshire. She enrolled her son at the New London Literary and Scientific Institution in New London.[10] But Adeline had higher aspirations for her son – West Point Military Academy – and she knew just whom to contact to make this happen. In October 1864 she wrote a letter to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant asking him to use his influence to get Robert an appointment to the school:

“Will you pardon me for asking you to take an interest in my humble affairs! My object is to learn if I could obtain your influence to have my son placed as a student at West Point. He is sixteen years of age, of a vigorous and healthy frame, and willing to be useful to his country.”[11]

Adeline told the general exactly why she felt he should aid her son:

“You may possibly remember our family we were the occupants of the ‘White House’ which stood outside of the Rebel fortifications at Vicksburg. You will recollect the destruction of our property, the house being on the battlefield. All we have left is a plantation now in the possession of Rebels, and of course lost to us. The Government of the United States has not yet paid us for what was destroyed by their army near this place. I am unable to finish the education of the boy, for whom I would ask you to interest yourself, by a few words of recommendation to President Lincoln. My husband died three weeks after the surrender of Vicksburg; he was a Union man in the strongest sense of the term, and stood firm for his country in her darkest hour even to the wreck of his fortune. While he lost his life from the fatigue which he endured, at the time of the siege.”[12]

As it turned out, General Grant did remember the Shirley family, and had reason to look on Adeline’s request favorably. He was once quoted during the Vicksburg siege as saying of James Shirley, “He is very intelligent, knows all about the country, and as I am well assured of his devotion to the Union, he gives me much needed information.”[13]

In February 1865 Grant wrote a letter of recommendation for Robert Q Shirley and sent it to Secretary of War; Edwin M. Stanton. Grant spoke in glowing terms of the Shirley family:

“This is one of the most deserving cases that can be found in the whole South. As Mrs. Shirley states her husband, and in fact the whole family, were Union people from the start ‘in the strongest sense of the term.’ The boy who Mrs. Shirley now desires to send to West Point showed the most decided loyalty on the advance of our troops upon Vicksburg. For several days from the commencement of the siege he kept his place in the front rank among our men, gun in hand, and only desisted after repeated orders to do so. I hope the President will find it practicable to appoint Robert Quincy Shirley, from the State of Miss.”[14]

General Grant’s letter of recommendation was duly forwarded to President Abraham Lincoln, and it was quickly acted on. A note was made on the manuscript by John G. Nicolay, the president’s secretary: “Respectfully referred by the President to the Secretary of War for consideration when appointments are made.”[15] In May 1865 Robert Q. Shirley was given an appointment to West Point, and the young man sent in his formal acceptance of the offer the next month.[16]

Unfortunately, from the beginning of his time at West Point, Cadet Robert Q. Shirley struggled academically. In 1866 he was “turned back;” and had to repeat some of his classes. Given the disruptions the war had made to his formal schooling, it is probable that the young man struggled with the rigorous academic load at the military academy. Unfortunately things did not improve for Shirley, and in 1868 he was “Found deficient & discharged.”[17]

After his dismissal from West Point, Robert Q. Shirley eventually drifted out west; and ended up in Logan, Utah Territory, where he served as postmaster in the late 1870’s.[18] He died of consumption on September 11, 1879, at the age of 30, and is buried in Logan City Cemetery in Logan, Utah.[19]

Jeff T. Giambrone is a native of Bolton, Mississippi. He has a B.A. in history from Mississippi State University and an M.A. in history from Mississippi College. He is employed as a Historic Resources Specialist Senior at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Giambrone has published four books: Beneath Torn and Tattered Flags: A Regimental History of the 38th Mississippi Infantry, C.S.A.; Vicksburg and the War, which he co-authored with Gordon Cotton; An Illustrated Guide to the Vicksburg Campaign and National Military Park; and Remembering Mississippi’s Confederates. In addition, he has written articles for publications such as North South Civil War Magazine, Military Images Magazine, Civil War Monitor, and North South Trader’s Civil War Magazine.

[1] Cotton, Gordon. “Shirley House Caught Between Armies at War.” Vicksburg Evening Post, (Vicksburg, MS) 14 June 1988.

[2] Eaton, John, and Ethel Osgood Mason. Grant, Lincoln and the Freedmen: Reminiscences of the Civil War. New York, NY: Longmans, Green, And Co., 1907, pg. 72.

[3] 1850 United States Census, Warren County, Mississippi, page 238a.

[4] When the 1860 United States Census was taken, James and Adeline Shirley had three children listed: Frederick age 24, Alice age 16, and [Robert] Quincy, age 12. 1860 United States Census, Warren County, Mississippi, page 1004.

[5] Eaton, John, and Ethel Osgood Mason. Grant, Lincoln and the Freedmen: Reminiscences of the Civil War. New York, NY: Longmans, Green, And Co., 1907, pg. 74-75.

[6] Ratliff, Mary. “The City of Vicksburg.” Confederate Veteran Magazine, Volume XXXVI, No. 10 (October 1928) pg. 398.

[7] Eaton, John, and Ethel Osgood Mason. Grant, Lincoln and the Freedmen: Reminiscences of the Civil War. New York, NY: Longmans, Green, And Co., 1907, pg. 77.

[8] Ibid, pg. 81.

[9] Ragland, Mary Lois. Fisher Funeral Home Records Vicksburg, Mississippi 1860-1865. Privately Published, 1986, pg. 80. A copy of this book is available at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, MS, 929.3/M69wa/F533r.

[10] Eleventh Annual Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the New London Literary and Scientific Institution. Concord: William Butterfield, Printer. 1864, pg. 9. Accessed on Ancestryinstitution.com, 19 December 2023.

[11] Adeline Shirley to Ulysses S. Grant; 3 October 1864. US, Military Academy Cadet Application Papers, 1805-1908; Robert Q. Shirley. Accessed on Fold3.com, January 2, 2024.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Eaton, John, and Ethel Osgood Mason. Grant, Lincoln and the Freedmen: Reminiscences of the Civil War. New York, NY: Longmans, Green, And Co., 1907, pg. 71.

[14] Ulysses S. Grant to Edwin M. Stanton, 15 February 1865. US, Military Academy Cadet Application Papers, 1805-1908; Robert Q. Shirley. Accessed on Fold3.com, January 2, 2024.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Robert Q. Shirley to Edwin M. Stanton, 5 June 1865. US, Military Academy Cadet Application Papers, 1805-1908; Robert Q. Shirley. Accessed on Fold3.com, January 2, 2024.

[17] US, Military Academy Cadet Application Papers, 1805-1908; Robert Q. Shirley. Volume 1; 1867-1868, page 76. Accessed on Fold3.com, January 2, 2024.

[18] Official Register of the United States, Containing a List of Officers and Employes of the Civil, Military, and Naval Service. Volume II, page 352. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1879.

[19] Utah, U.S., Cemetery Inventory, 1847-2021; U.S., Federal Mortality Schedules Index, 1850-1880. Accessed on Fold3.com, January 2, 2024.

This was a great read. I knew of the house, but not the story behind the residents and their loyalty. Thanks for sharing!

So, if James Shirley “helped” Gen. Grant during the siege, then he displayed loyalty to his former country, while betraying his current state.

Tom

Jeff, great article. Recommend you continue this story about what happens to the Shirley House during the period of post-siege and to the establishment of the VNMP in 1899; and even up to current day. You might add a introductory about the original owner. Question: where was the White House Battery located? Tony

Tony, I’m glad you liked it! I will definitely consider a follow up story on the Shirley House. The White House Battery was located 25 yards southeast of the Shirley House. It was manned by Company D, 1st Illinois Light Artillery, who were serving four 24-Pounder howitzers.