The Union Great Skedaddle of February 6, 1865. Part 1: Chaos Around Dabney’s Mill.

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Nigel Lambert…

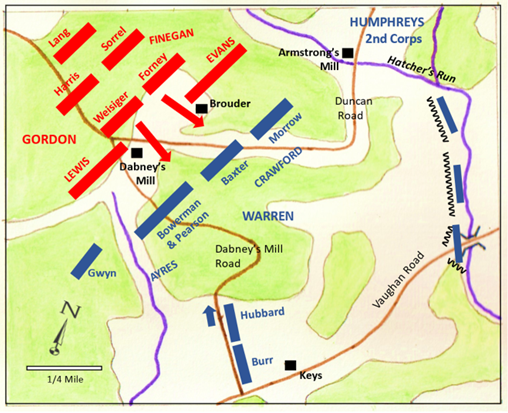

During the siege of Petersburg, the Union’s eighth offensive aimed to destroy a Confederate supply route using Boydton Plank Road. This culminated in the battle of Hatcher’s Run. On the second day of the battle, Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon’s Confederates tussled with Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s V Corps soldiers for three hours in dense woodlands and swamps around Dabney’s Mill [1]. The site changed hands many times as each side brought fresh troops to the fight. At around 5:00 p.m., a noticeable lull occurred. The Rebels tried to address a fracture in their line and reorganize after losing two senior commanders [2]. The Federals began entrenching southeast of the mill. Both sides anxiously awaited reinforcements, namely Maj. Gen. Frank Wheaton’s (VI Corps) soldiers for the Union and Brig. Gen. Joseph Finegan’s troops for the Confederates [3].

With rain lightly falling, Finegan’s men arrived first. Gordon formed the five fresh brigades behind Brig. Gen. Clement A. Evans’s division and troops, now commanded by Brig. Gen. William G. Lewis [4]. This resolved the gap within the Rebel lines. Gordon quickly devised a plan. Finegan would spearhead a two-wave frontal attack against the Federal position. The first wave would comprise Col. William H. Forney’s Alabamians on the left and Brig. Gen. David Weisiger’s Virginians to their right [5]. The second wave would include Brig. Gen. G. Moxley Sorrel’s Georgians on the left and Brig. Gen. Nathaniel H. Harris’s Mississippi Brigade on the right. Finegan would hold the Florida Brigade under Col. David Lang in reserve [6]. Finegan guided his horse to the lead brigades and ordered a charge. “On ye go you brave lads,” he shouted. With a yell, the two brigades moved forward through the woods.

The word “pandemonium” best summarizes what followed. Eyewitnesses and historians alike have mostly minimized and/or misunderstood the dramatic events that occurred in the gloom of February 6, 1865.

Supported by Rebel artillery and elements of Gordon’s command, Finegan’s first wave crashed into the Union position. Brigadier General Henry Baxter’s brigade held the Union center, with Brig. Gen. Henry A. Morrow’s brigade on the right flank and the brigades of Brig. Gen. Alfred L. Pearson, Col. Richard N. Bowerman, and elements of Brig. Gen. James Gwyn’s brigade on the left.

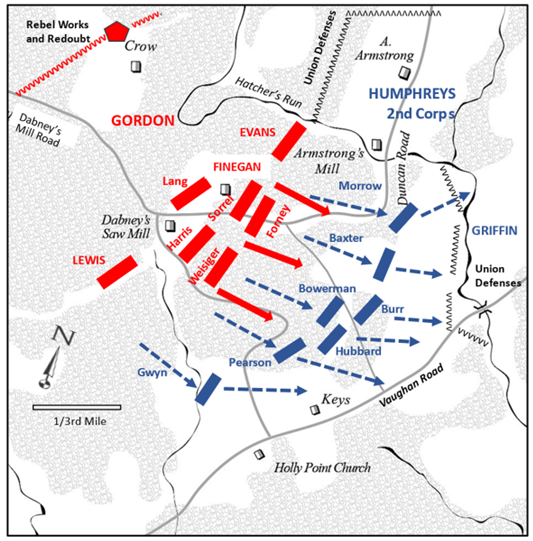

Parts of the blue line started to buckle. Finegan’s second wave, Sorrel’s Brigade and Harris’s Brigade joined the fight, heaping further pressure on the Federal position. Alarm grew within the Federal ranks. Rebels heard Yankee officers trying unsuccessfully to turn their troops to the front with cries of “Go back, go back!” But the Union line broke. Panic and confusion gripped the Yankees, who started to flee pell-mell to the rear.

Finegan, still with the Virginia Brigade, became wildly excited. “Pursue them, me brave Virginny boys, they run like deer,” he shouted in his rich Irish brogue. The jubilant Confederates chased the terrified Yankees, who headed for the sanctuary of their works along Hatcher’s Run and Vaughan Road. Colonel Forney proudly recalled how his Alabama Brigade “drove [the Federals] back easily and did it handsomely.”

Union division commander Maj. Gen. Romeyn B. Ayres tried to rally the routed Yankees on some ridges in open ground in front of the Union breastworks. His efforts proved unsuccessful. Many Union memoirs justified their own retreat by blaming a lack of ammunition and adjacent units running away or firing into them.

A captain from the 83rd Pennsylvania described the affair as “the greatest skedaddle that has taken place yet.” Major Mason W. Tyler (37th Massachusetts) watched the drama unfold. “I never saw such a rout, and it made me so mad I wanted to shoot some of the officers, who were as bad as the men – scared to death.” He noted that Maj. Gen. Samuel W. Crawford’s division “was repulsed, and a causeless panic seized them and they ran more than a mile [with] . . . no enemy of any consequence following them.”

Finegan’s elite veterans ruthlessly executed their attacks. The stunning Rebel charge evoked memories of former Confederate glories. Indeed, this would be one of their last “great hurrahs” of the war.

And what of the Union reinforcements? As ordered, Wheaton directed one of his brigades (Col. James Hubbard commanding) towards Dabney’s Mill. Colonel Allen L. Burr’s brigade (Griffin’s division), then on Vaughan Road, received orders to follow Hubbard’s troops. Hubbard’s brigade began forming a line on open ground more than 400 yards in front of the Hatcher’s Run defenses. They soon saw many soldiers (fleeing Yankees) running toward them. Some fired at the onrushing men in the gloom, mistaking them for Rebels.

A line proved impossible to form as the routed Yankees smashed into Hubbard’s formation, disrupting and panicking his men, and they all headed to the rear. However, they ran toward Col. Burr’s brigade, also trying to form a line. Some of Burr’s troops panicked and fired at the onrushing mass of Yankee fugitives before joining the routed mob fleeing the attacking Rebels and running toward the Union defenses.

The chasing Confederates grew increasingly disorganized as they charged through dense woods and swamps. In near darkness, the Rebels became exhausted after pursuing the Yankees for nearly two miles. Once behind their substantial earthworks, manned by reserve troops, the Federals finally halted the Rebels. In addition, the Confederates began receiving fire from Union II Corps artillery across Hatcher’s Run near Armstrong’s Mill. The fighting fizzled out, with the Rebels victorious. Although routed and stunned, the Yankees had found safety within their works.

At 7:30 p.m., army commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade messaged Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and reported having a “spirited contest with the enemy.” He relayed how the Rebels had opened on them with artillery and received reinforcements. This had compelled Warren’s troops “to retire in considerable confusion.” Meade explained that Warren’s troops had eventually halted the Rebel advance. Union losses were considerable, although Meade couldn’t give an estimate. There is no record of Grant’s reply.

A combination of factors provoked the Union skedaddle. Many of the V Corps soldiers were inexperienced. Before that afternoon, some had never fired a rifle. With ammunition-supply wagons getting stuck along the narrow, muddy trails, units became starved of ammunition. As one soldier explained, “The best of men will not stand with empty muskets and be shot down.” The Union force involved intermingled brigades from four different divisions. In such circumstances, coordinating areas of responsibility and fields of fire becomes challenging and confusing.

In addition to facing the aggressive Confederate assaults on their front, the Federals were subjected to friendly fire. With firing coming from multiple directions, such exposed Federal troops hastily retreated. As one part of the Union line fled, adjacent troops became isolated and vulnerable to Confederate flanking fire. This created a domino effect. Panic gripped many of the inexperienced, confused, and frightened soldiers. Therefore, instead of undertaking an orderly withdrawal, a mass stampede ensued.

Darkness and the recently created breastworks along Hatcher’s Run saved V Corps from a substantial disaster. How Union commanders processed the debacle rarely receives commentary. This is the subject of Part 2.

Dr. Nigel Lambert is a retired British academic who lives near Norwich, England. He has published many bioscience and social science articles linked to various medical issues. A life-long Civil War enthusiast, he recently became interested in the battle of Hatcher’s Run. Surprised by the sparse and conflicting literature on the battle, he employed his scientific and qualitative research know-how to advance our understanding of the battle. Working with US experts on the Petersburg campaign, he has created an extensive e-library for the battle. Using this database, he has authored two articles in North&South magazine article and five articles on the “Siege of Petersburg Online” website. A book chapter describing the battle is currently under review.

Notes

[1] Little remained of the actual steam sawmill. A large sawdust pile occupied the site.

[2] Division commander Brig. Gen. John Pegram (killed) and brigade commander Col. John Hoffman (wounded) had fallen in the previous Yankee surge on the mill.

[3] With Maj. Gen. William Mahone absent, Finegan commanded the renowned Mahone’s Division.

[4] Lewis replaced Pegram as divisional commander.

[5] One article claimed Col. Gustavus Groner commanded the Virginia Brigade that afternoon.

[6] The Florida Brigade was Finegan’s own brigade. Some claimed they also attacked in a third wave.

[7] I thank Bryce Suderow for supporting my research and George Skoch for allowing me to use his baseline map.

Main Sources

Ed Gleeson, Erin Go Gray (Cincinnati, OH,1998), 35-37.

John Horn, The Petersburg Regiment in the Civil War (El Dorado Hills, CA, 2019), 358-59.

Nigel Lambert & Bryce A. Suderow, “The Battle of Hatcher’s Run: A Re-Appraisal,” North & South Magazine (January 2022) Series 2, Vol. 2, No. 5, 35-46.

Edwin C. Bearss & Bryce A. Suderow, The Petersburg Campaign, 2 vols. (El Dorado Hills, CA, 2014), 2:215-18.

OR 46/1:152.

OR Supplement 7:717, 807.

Ronald G. Griffin, The 11th Alabama Volunteer Regiment in the Civil War (Jefferson, NC, 2008), 219.

Lee W. Sherrill, The 21st North Carolina Infantry: A Civil War History, with a Roster of Officers (Jefferson, NC, 2014), 415.

Amos M. Judson, History of the 83rd Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers (Erie, PA, 1865), 110.

Mason W. Tyler &. William S. Tyler, Recollections of the Civil War (New York, 1912), 329-31.

Alfred S. Roe, The 39th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers, 1862-1865 (Worcester, MA, 1914), 272-73.

Emerson G. Taylor, Gouverneur Kemble Warren: The Life and Letters of an American Soldier, 1830–1882 (New York, 1932), 203-04.

Great stuff! Just as the Petersburg Campaign is often underrated in its importance to the outcome of the war, so is Hatcher’s Run’s importance to the Petersburg Campaign. Keep these informative articles coming!

Thanks Tim. Yes, there are lots of mostly forgotten fascinating tales from those three terrible days in Feb 1865.

Gripping narrative! Definitely an eventful day for all involved by the sounds of it..

Great post and I am glad to see it here!

The narrative brings the events, timeframe and context together in an engaging and coherent way. More please.