The Union Great Skedaddle of February 6, 1865. Part 2: Union Commanders Process the “Discomfiture.”

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Nigel Lambert…

Army commander George G. Meade called the V Corps rout at Hatcher’s Run “a disaster.” Artillery chief Col. Charles S. Wainwright scathingly wrote, “Our men were regularly stampeded . . . all the officers . . . say it was disgraceful beyond anything they had ever seen [from] . . . the V Corps.”

The Army of the Potomac had a reputation for cronyism and retribution. These traits could quickly surface following significant battlefield successes or failures. Poor performances on this scale threatened careers, and no officer wanted to endure a military inquest. Official reports from senior commanders appearing days after the debacle at Hatcher’s Run make for interesting reading [1]. Often low on details, the carefully crafted narratives brim with self-justification. Many attempted to deflect blame away from themselves and onto others. How senior Federal officers processed this humiliating defeat is overlooked, yet it played a significant role in how posterity portrayed the battle.

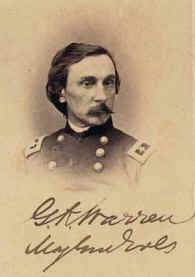

The report of Gouverneur K. Warren report minimized the defeat, saying, “On the whole, it was not a bad fight and in no way discouraged me . . . to try the same thing again with the same men.” Despite overwhelming evidence showing that Union soldiers had fired into their comrades, some of which he witnessed personally, Warren denied in his report that such events occurred. His private opinions, however, were more critical; “We are getting to have an array of such poor soldiers that we have to lead them everywhere, and even then, they run away.”

Warren targeted his severest criticism towards Burr’s brigade. Burr had followed Col. Hubbard’s VI Corps brigade to reinforce Warren’s force. Caught up in the stampede, Burr claimed he rallied his troops and advanced, “driving the enemy and doing good execution.” Warren summarily rejected Burr’s report, noting how he had seen this brigade fire into Maj. Gen. Ayres’s troops and Hubbard’s brigade. He added, “The men fell out of line rapidly and joined the fugitives from other brigades . . . The newness of the organization is the best excuse . . . for such conduct and demands . . . efforts of its officers to discipline the men and make them steadier in the excitement of battle.”

Mostly raw recruits, Burr’s troops were convenient targets for Warren’s wrath [2]. Burr only led the brigade because the regular commander (Brig. Gen. Edgar M. Gregory) was on leave. As Burr’s men tried forming a line in the near darkness, many soldiers raced toward them. Were they friends or foes? Furthermore, many Rebels wore stolen Union blue coats. Some of Burr’s brigade fired on the soldiers (retreating Federals, as it happened). In the stampede, many panicked and fled. Crucially, they were not the only brigade guilty of friendly fire that afternoon.

There is probably some truth in both versions of events. A number from Burr’s brigade could have fled in panic, firing wildly, whereas others might have remained with Burr and stood firm. Modern accounts have echoed Warren’s narrative and singled out Burr’s men for blame. However, many V Corps soldiers had panicked and fled long before encountering Burr’s brigade. Burr’s men subsequently bought him a new horse in praise of his sterling leadership at the battle!

Warren also admonished division commander Ayres and his two brigade commanders, Col. Bowerman and Brig. Gen. Gwyn. Their reports lacked details, and Warren returned them demanding amendments. To Ayres, Warren said that he didn’t “think there were sufficient reasons for good troops to give way” and that the losses were insufficient to justify a retreat. The orders had been to remain and fight. Warren stated that his reports would not shield his troops. He added, “If they won’t fight the country must know it.” Warren acknowledged that Ayres had tried to control his troops, and for the honor of the corps, he wished “to have it plainly stated that it was the troops and not the generals who would not fight.” Ayres replied that some of Maj. Gen. Crawford’s troops fired on two of Brig. Gen. Pearson’s regiments sent to support Bowerman. Pearson’s men ran away, which “caused a retrograde movement all along the line . . . [and] was against all orders and authority.”

In rejecting Bowerman’s report, Warren shared his skepticism that Bowerman’s troops had run out of ammunition. “If brigades withdrew without being ordered to do so, charges would be issued against the officers.” The criticism of Bowerman seemed particularly harsh. Three of his soldiers received Medals of Honor for their deeds that afternoon. Meade later issued a report formally praising Bowerman’s brigade and issued furloughs to several soldiers as a reward for their bravery. In rejecting Gwyn’s report, Warren opined “that the brigade left the front without orders and without encountering a sufficient force of the enemy to justify it.”

In marked contrast, no evidence indicates that the other commanders involved in the rout received similar criticism or had their reports returned. Pearson’s brigade had supported Ayres’s troops. He reported that friendly fire from the rear by Crawford’s troops and a mass of disorganized and demoralized VI Corps troops had caused his brigade to break. Unfortunately, the report of Crawford, the other division commander pivotal to the defeat, is missing from the records. However, many of his senior officers submitted reports. Baxter’s brigade had occupied the Union center, while Morrow’s brigade held the right [3]. Reports from these units were equally minimal. Both brigades claimed that they ran out of ammunition. An officer with Morrow reported that Baxter’s men fell back, and thus, Morrow’s troops had to retire to save themselves.

Despite many of Warren’s officers accusing Hubbard’s VI Corps brigade of discharging friendly fire, they also avoided criticism. Indeed, Maj. Gen. Wheaton, Hubbard’s division commander, claimed Warren praised his men for stabilizing the Union line.

The reports of two V Corps staff officers conveniently aligned with Warren’s beliefs. They wrote how Burr’s men had fired into their comrades before running away. They also saw many stragglers from Ayres’s division breaking to the rear. In contrast, both pointedly remarked how Crawford’s division had “retired in good order.”

The debacle never reached the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Grant, Meade, and Warren seemed content to blame the inexperienced troops and move on. Some accused Grant and V Corps reporters of covering up the embarrassment.

In the following years, Unionists conveniently forgot the “great skedaddle” of February 6. The fight did not feature in Grant’s memoirs and only received a short line in Meade’s letters. An acclaimed 1882 book on the Army of the Potomac said little about the affair, noting only that the Federals retreated in a “discomfiture.” [4] An 1896 seminal book on the 5th Corps didn’t particularly portray the engagement as a failure [5]. It mentioned how the Federals fell back due to a lack of ammunition and the onset of darkness before Wheaton, supported by others, checked the Rebels. Neither book mentioned the chaotic rout.

The combatants’ desire to preserve their pride and honor was important in creating narratives. A private in the famed 20th Maine (Pearson’s brigade) described the rout in his memoir thus: “There are some facts connected with that battle which we would not want everyone to know . . . how we got frightened and ‘skedaddled’ back through the woods like a flock of sheep. . . for the reputation of the regiment we will not speak minutely of those things here.” [6]

Once narratives become set, they can echo through the decades. Recent books on Crawford and Baxter (both pivotal to the fight) overlooked the debacle [7]. The Union “skedaddle” of February 6, 1865, remains in the shadows.

Dr. Nigel Lambert is a retired British academic who lives near Norwich, England. He has published many bioscience and social science articles linked to various medical issues. A life-long Civil War enthusiast, he recently became interested in the battle of Hatcher’s Run. Surprised by the sparse and conflicting literature on the battle, he employed his scientific and qualitative research know-how to advance our understanding of the battle. Working with US experts on the Petersburg campaign, he has created an extensive e-library for the battle. Using this database, he has authored two articles in North &South magazine article and five articles on the “Siege of Petersburg Online” website. A book chapter describing the battle is currently under review.

Notes

[1] Although extensive for this action, the OR are incomplete.

[2] The brigade was only formed in October 1864.

[3] Morrow was severely wounded during the rout.

[4] William Swinton, Campaigns of the Army of the Potomac (New York, 1882), 547-49.

[5] William H. Powell, The Fifth Army Corps (Army of the Potomac) A Record of Operations During the Civil War in the USA, 1861–1865 (New York, 1896), 760-61.

[6] Theodore Gerrish, Army Life; a Private’s Reminiscences of the Civil War (Portland, ME, 1882), 223-24.

[7] Richard Wagner, For Honor, Flag, and Family (Shippensburg, PA, 2006), 226; Jay C. Martin, General Henry Baxter, 7th Michigan Volunteer Infantry (Jefferson, NC, 2016).

Main Sources

OR 46/1:153, 255-56, 258-61, 269-72, 276-79, 282-85, 292, 298-99.

OR 51/1:286, 288, 291-92.

Allan Nevins, ed., A Diary of Battle: The Personal Journals of Colonel Charles Wainwright, 1861-1865 (San Diego, CA, 1962), 497.

Charles Camper & Joseph W. Kirkley, Historical Record of the First Regiment Maryland Infantry. War of the Rebellion, 1861-65 (Washington, 1871), 189-90.

Emerson G. Taylor, Gouverneur Kemble Warren: The Life and Letters of an American Soldier, 1830–1882 (New York, 1932), 203.

William H. Rogers, History of the 189th Regiment of New-York Volunteers (New York, 1865), 92-95.

Have you come across any enlisted men mentioning a fear of being captured as prisoners of war as a motivation for running? At this point in the war it was quite well known how horrible prisoner of war camps could be on both sides. On the surface, it is perhaps not as justifiable as being out of ammunition or collapsing due to adjoining units doing so, but few soldiers wanted to be prisoner at this point, despite exchanges starting again soon.

That’s an interesting point. Many soldier memoirs were quite evasive of the action, it was usually “other” regiments who ran away. I have no source specifically mentioning the fear of being captured. However, It’s quite probable that Libby or Andersonville were on Union soldiers’ mind. From what we do know, the Federal soldiers didn’t hang around and risk capture.

The blame game is always an interesting one after a defeat or a controversial victory. Grant was able to get negative attention focused on Wallace after Shiloh for example although Grant still suffered a knock on his reputation.

Good point Sean. Given his humble origins, Grant seemed to be well skilled in media presentations – that’s a useful talent to have as a military leader and probably why he ended up in politics and getting the top job. Not sure where he got that skill from?