“This is an entire mistake”: The First Shots in Virginia

ECW welcomes back Drew Gruber and welcomes guest author Owen Lanier.

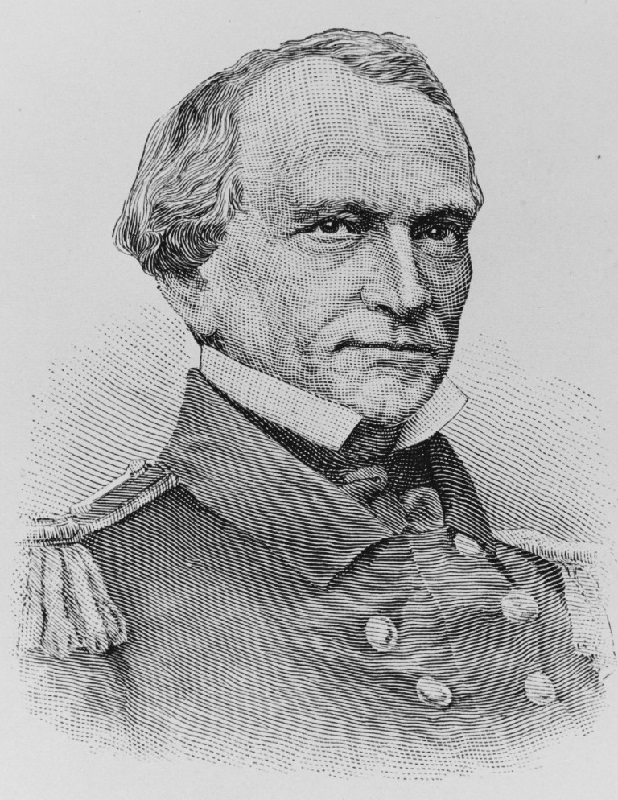

It is never a good day when you must write to your boss’s boss about an issue at work, especially when the situation revolves around you being the first person to shoot at another nation – for the first time. On May 8th, 1861, Capt. William C. Whittle Sr. of the Virginia Navy penned a note to Maj. Gen. Robert E. Lee, who commanded Virginia’s forces. It was four, short sentences. Whittle concluded the brief missive by saying, “This is an entire mistake.”[1]

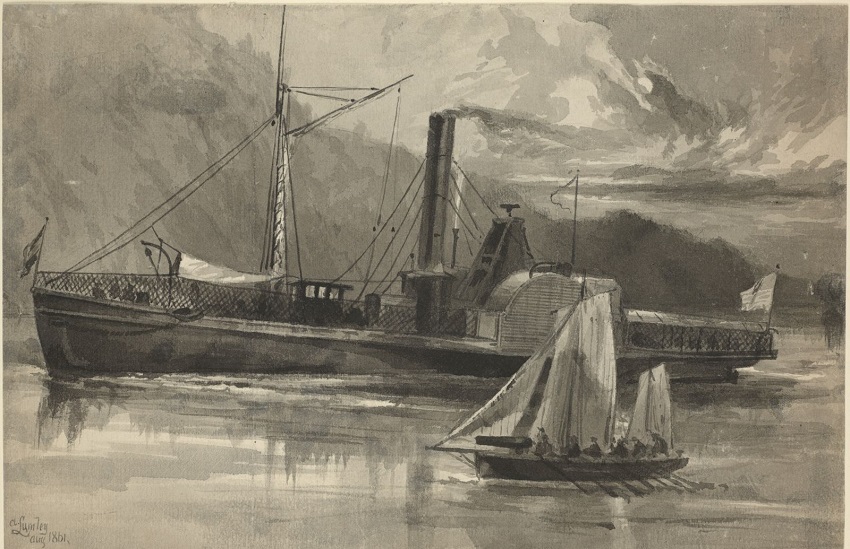

The day before, Whittle commanded the Virginians who pulled the lanyard, sending a warning shot across the bow of USS Yankee as the tug steamed up the York River towards Gloucester Point. For a few short minutes on May 7, Whittle’s men ended up firing a dozen rounds at Yankee. Only 20 days earlier Virginia voted to leave the Union.

Historians are quick to point to the skirmish at Arlington Mill on June 1, the battle of Philippi (now West Virginia) on June 3, or Big Bethel on June 10 as Virginia’s “first” engagements. But it is here on the now sandy beach at Gloucester Point that a naval officer made a choice. Did he regret it? Was this a mistake? Perhaps the order was given in haste?

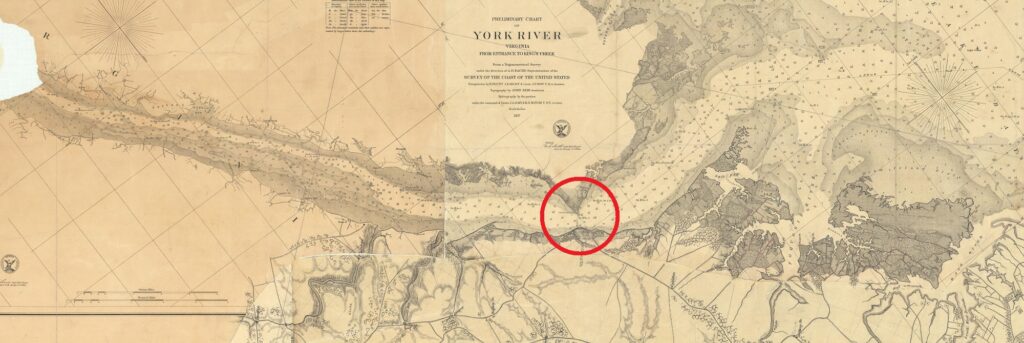

One of the units assigned to defend Gloucester Point was a section of the Richmond Howitzers under Lt. John Thompson Brown. Gloucester Point’s strategic value was well known before 1861. Most famously during the 1781 Siege of Yorktown, the narrow stretch of the York River between Yorktown and Gloucester Point created an easily defensible position. However, Virginia did not plan to retain the 1781 British defenses. Immediately after the British surrender at Yorktown, George Washington directed his engineers to level the fortifications, fearing a renewed British effort to seize the South. So quickly after Virginia seceded from the Union on April 17, construction of several new fortifications began at Gloucester Point.

A few days later, on May 3rd, Maj. Gen. Lee wrote to William Booth Taliaferro, a native of Gloucester County, informing him that he was appointed colonel of Virginia volunteers. In that note Lee mentions that a battery under the command of Capt. Whittle from the Virginia Navy was already under construction at Gloucester Point.[2] Taliaferro accepted the commission, writing to Lee three days later. In that letter, almost as if he had a premonition, Taliaferro asked, “In the event of a ship of war of the United States attempting to pass the batteries on Gloucester Point … is the attempt to be resisted, or shall I await the institution of more decisive hostilities on the part of the United States authorities?”[3]

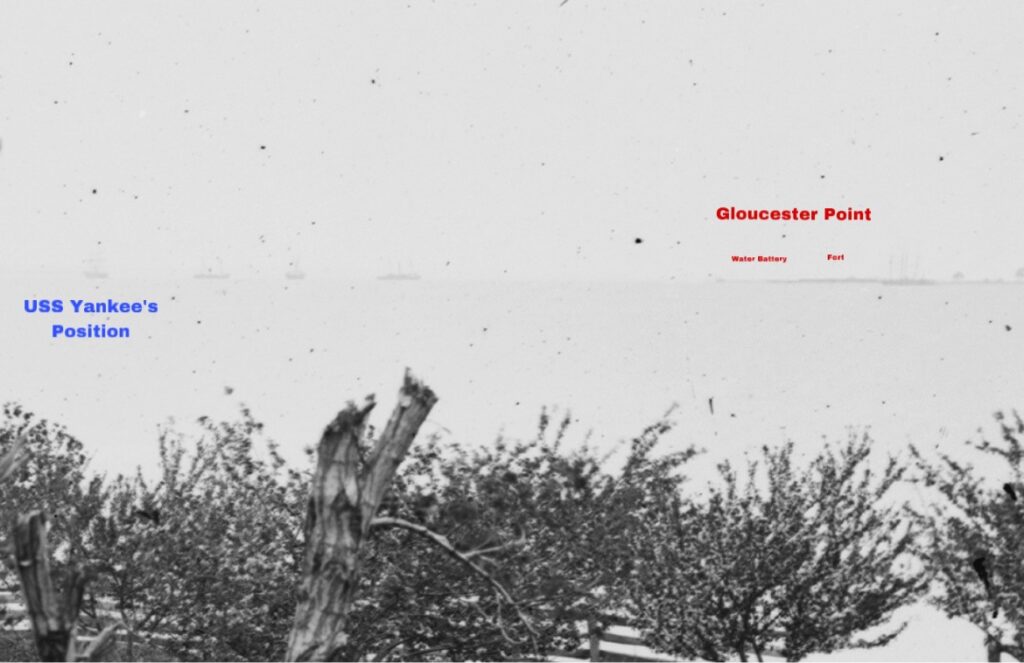

Taliaferro’s fears were realized just three days later when Union Lt. Thomas Selfridge sailed up the York River on a reconnaissance mission. Selfridge reported that while the York River was not obstructed “there is in the course of erection a breastwork, or water battery, which when completed will command the approach of the river.” He continued, “In its present condition it is useless for defense” and believed that “a small steamer could prevent the further progress of the work at Gloucester Point, as I firmly believe there are no heavy guns in the neighborhood.”[4]

The following day, May 7, 1861, Lt. Selfridge boarded the tug Yankee and steamed from Hampton Roads at 10 a.m. to closely examine the Gloucester Point defenses. As Yankee closed the water battery Selfridge deemed useless just 24 hours before, a shot rang out, zipping towards him. “A shot across my bow first appraised me that the enemy had guns mounted,” he recalled. As Yankee steamed westward another shot came hurtling “in line, but a little short.” barely missing Selfridge and the Union sailors. He ordered the two 32-pounder guns on board shifted to port, firing six rounds “at extreme elevation,” but was disappointed to find they fell short of Gloucester Point.[5]

The first company of the Richmond Howitzers manned a mix of six-pound field guns and twelve-pound howitzers that day. Using the effective ranges of the Confederate cannon and channel charts from the time, it is safe to say the battle began just off modern-day Yorktown beach. The first warning shots streaked approximately 1,200 yards across the tug’s bow. As the Union crew turned to starboard near present-day Yorktown pier to present its two 32-pounders, the Virginian twelve-pound howitzers joined in.

The Confederate gunners were attempting to hit Yankee at ranges of 1,000 yards with smoothbore weapons left over from the 1840s. When you factor in that Yankee’s hull rose a mere 10 feet above the waterline, it becomes apparent the Virginians were trying to hit a terrifyingly small target. According to Selfridge, Yankee was the target of a dozen Confederate rounds. By his estimate the Confederate guns at Gloucester Point, manned by what Selfridge estimated as 40 men, outmatched him.[6] On the other hand, Yankee’s guns couldn’t even aim high enough to return the favor. It is no wonder that the battle saw zero damage and produced no casualties. Neither side expected an engagement or was particularly motivated to do great violence that day, and neither side yet had great skill in gunnery that made sieges such as at Vicksburg surmountable.

The day following the sharp action between Yankee and the Gloucester Point garrison, Maj. Gen. Lee responded to the nervous note from Taliaferro asking what he should do if a Union vessel should try to pass by Gloucester Point, advising the colonel that “on the approach of a vessel of the enemy, and when she shall have gotten within range, to fire a shot across her bows. Should this not deter her from proceeding on, you will fire one over her. Should the fire be returned you will capture her if possible.”[7] Although a day late, this was exactly what Whittle’s and Brown’s gunners did.

On May 9, the Richmond Dispatch broke the news in a short piece which offered some detail to the public: “A rumor, which we could trace to no authoritative source, prevailed here yesterday, that a detachment of Virginia Artillerymen, stationed at Gloucester Point, or some other place down the river, had fired into one of Lincoln’s ships that had been discovered in too close proximity to the shore, sounding, and that the piratical craft had returned the salute, and then cut out. It is presumable, of course, that if our men saw the enemy, they fired on him. The engagement alluded to above is rather misty…”[8]

Details provided by the Richmond Dispatch did not improve much by May 11 when the paper ran a follow-up: “The fact that one of Lincoln’s roving pirates was fired on a few days ago, at Gloucester Point, by some Virginia artillerymen, has been mentioned.–The boat (the Yankee,) attempted to pass the fortifications at that place, when six rounds were fired at her, which drove her back. Captain J. Thompson Brown, who commands at Gloucester Point, is of opinion that he could have sunk her. His orders were only to prevent her passing, which he did. A liberal construction of his orders would have been justified under the circumstances of the case.”[9]

Shortly thereafter Capt. Whittle was transferred up to West Point, Virginia. The Gloucester Point garrison saw little, if any, excitement following the May 7, 1861, action, until the following spring when George McClellan’s massive Army of the Potomac arrived in and around Fort Monroe, at the tip of the Virginia peninsula. The importance of the Point and its proximity to York again came into play, preventing the United States army and navy from sailing around the Confederate defenses which blocked their way up the Peninsula and the Confederate capital in Richmond. Although elements of the Union army’s I Corps practiced scaling heights and floating artillery batteries with the eye of taking Gloucester Point, no direct assault on the Point manifested during the 1862 Siege of Yorktown.

The Gloucester Point garrison remained until May 3, 1862, when it withdrew towards Richmond with Joe Johnston’s army at Yorktown. They carried off a few of their guns, eight- and nine-inch Dahlgrens by then, but the majority were left behind. For the rest of the war the Union army controlled Yorktown and Gloucester, launching raids and tying down Confederate forces. USS Yankee spent the rest of the war capturing Confederate vessels and launching raids, finally decommissioning on May 16, 1865.

Today, when visiting Gloucester Point, begin your exploration at Tyndell’s Point Park located at 7418 Battery Dr., Gloucester Point, VA 23062. The park offers an easy walking path and several interpretive signs to help guide you through a series of extant earthworks. From there, drive over to Gloucester Point Park located at 1255 Greate Rd., Gloucester Point, VA 23062, and stand in the footsteps of Capt. Whittle and the gunners from the Richmond Howitzers.

Drew Gruber is the executive director of Civil War Trails.

Owen Lanier is a student at Gettysburg college and an employee at the American Battlefield Trust.

Endnotes:

[1] The War of the Rebellion: The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (OR), Series I, Vol. II, 821.

[2] Ibid, 800.

[3] Ibid, 812.

[4] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Vol. 4, 376.

[5] Ibid, 380.

[6] Ibid.

[7] OR, Series I, Vol. II, 815-816.

[8] “Rumored Engagement,” Richmond Dispatch, May 9, 1861.

[9] “The attack on the Yankee,” Richmond Dispatch, May 11, 1861.

Was this the Lt Thomas Selfridge who would “go Western theater, young man”, after escaping the CSN Virginia-sunk Cumberland, have a few ironclads sunk underneath him, and rise to the rank of Rear Admiral? Nothing succeeds like surviving!

Yes John. It is the same person. I believe Selfridge was already on Cumberland when this happened, and he was temporarily detached for the events described.

This article makes it sound like Whittle called the firing itself a mistake. I believe Whittle was referring to Taliaferro’s assertion that he ordered the battery to fire on the ship. He wrote “I know not [by] what authority Colonel Taliaferro says that the firing at Gloucester Point was authorized by me. This is an entire mistake.” It’s likely Lieutenant Brown gave the order. Taliaferro wasn’t there, so he probably just assumed the order was given by Whittle. In any case, I think this article gives the wrong impression by leaning on this quote taken out of context.