Who’s in Charge? Command and Control on the Rivers

Because we know what happened, it is easy to overlook the ad-hoc character of the Civil War, the degree to which our ancestors made it up as they went along. This is particularly true of the river war where the United States Ram Fleet provides an excellent illustration of enterprising innovation coupled with command confusion and lack of coordination.

Warfare on heartland waters had no precedent in 1861: no tactics, no warcraft, no infrastructure, no command structure. Neither the army nor the navy had any such experience, much less had they ever worked together in massive joint operations. Civilian rivermen and pilots—a different breed—along with western entrepreneurs and engineers would play central roles in the river fight.

Within a year, the Union Western Gunboat Flotilla had become a powerful riverine combat force employing unprecedented ironclads and gunboats with hundreds of transport and supply vessels. The flotilla was officered and crewed by U.S. Navy personnel but in an extraordinary and informal arrangement, was assigned to operational command of the army reporting to department commander, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck.

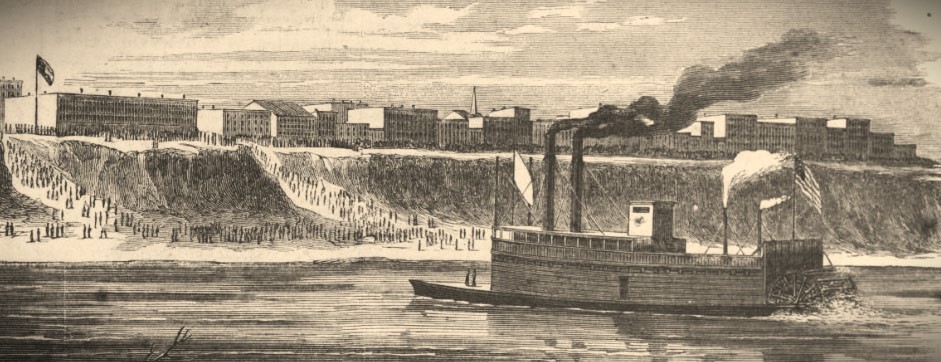

The Northern waterborne juggernaut—army and navy—had conquered Forts Henry and Donnelson, surged up the Tennessee River for the battle of Shiloh, and purged the Mississippi River of Rebel forces on land and water down past Columbus, Kentucky and Island No. 10 deep into Tennessee. Memphis was next.

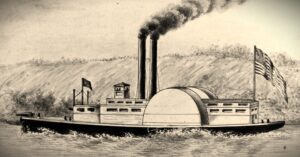

Three quasi-naval commands would clash there on June 6, 1862, in the only fleet engagement on the rivers and the first to employ steam-driven rams on both sides. Five river ironclads of the Gunboat Flotilla—commanded by Flag Officer Henry H. Davis—were joined by the unconventional United States Ram Fleet to oppose the equally strange Confederate River Defense Fleet.

The latter two “fleets” were uncannily similar. Both were volunteer organizations of civilian rivermen nominally under army supervision but inexperienced in military affairs operating improvised vessels employing that ancient naval weapon, the ram, which had not been seen for three centuries. Their respective navies played no role in these ventures.

The Confederate River Defense Fleet was the brainchild of two experienced Mississippi River steamboat captains apprehensive about the lack of naval forces protecting New Orleans. Joseph E. Montgomery and J. H. Townsend proposed a fleet of low-cost, steam-powered river rams capable of knocking big holes in and sinking Union warships.

Secretary of War Judah Benjamin approved the plan. Maj. Gen. Mansfield Lovell confiscated fourteen steamboats, attached iron rams to the bows, reinforced the hulls, and mounted a few guns. Lovell ordered eight of the rams with Captain Montgomery in charge up to Memphis to help defend the northern flank from the descending Union flotilla.

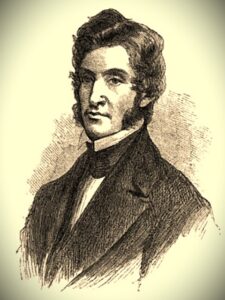

Simultaneously, Charles Ellet, Jr., another expert riverman and a prominent civil engineer from St. Louis, convinced Union Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that he could assemble a fleet of steam rams manned by volunteer rivermen to conquer the Mississippi. Bypassing the military bureaucracy entirely, Ellet purchased seven sternwheelers and sidewheelers at Pittsburg and Cincinnati and converted them to rams in local boatyards.

When Stanton offered Ellet a staff colonel’s commission, he expressed a preference for no military rank. Implied but not stated: Ellet and his men knew rivers and rivercraft and could confidently navigate treacherous inland waters whereas soldiers and sailors did not and could not. All he had to do was aim the rams at the enemy; what need had he of military trappings and chains of command? But if the secretary deemed it indispensable, Ellet would appreciate a grade higher, presumably equivalent to the navy flag officer in charge of the Western Gunboat Flotilla.

The commission was important, Stanton answered, as it provided legal authority to command while a colonelcy was the highest rank he could offer without congressional approval. Charles Ellet’s brother, Captain Alfred W. Ellet of the 59th Illinois Volunteers, would be appointed a lieutenant colonel as second in command. The secretary further instructed that Ellet’s ram expeditions “must move upon the enemy with the concurrence of the naval commander on the Mississippi River, for there must be no conflicting authorities in the prosecution of war.”[1]

Ellet also objected to the term “concurrence.” His purpose was not to hang around with gunboats but to drive against the enemy wherever found relying on suddenness and audacity of attack. “I fear that the naval commander might not concur in the propriety of such a movement, which is not in accordance with naval usage.” He did not wish to lie idle until the spring high water abated and surprise was lost. Would the secretary reconsider, leaving him free to act on his own judgment with “respectful deference to the gallant officer in command on the Mississippi?”[2]

Stanton returned a quintessentially bureaucratic response: The expression “concurrence” did not place Ellet directly under naval command. “As the service you are engaged in is peculiar, the naval commander will be…desired not to exercise direct control over your movements, unless they shall manifestly expose the general operations on the Mississippi to some unpardonable influence, which is not however anticipated.”

Two days later (unbeknownst to Ellet), the Secretary contradictorily informed General Halleck at Pittsburg Landing that the steam rams “are under command of Colonel Ellet, specially assigned to that duty. He will be subject to the orders of [Flag Officer Davis] and will join him immediately…. I hope this arrangement will be acceptable to you.” Command confusion and conflict would result.[3]

Sixty days from the time Ellet received his commission, recalled former ironclad sailor Eliot Callender, “he was on the way down the river with five powerful boats filled in at the bows and around the boilers, and manned by some of the most desperate characters that entered the service on either side; friend feared them as well as foe, they acknowledged allegiance to neither army or navy, but claimed to have a contract to settle the rebellion in their own way.”[4]

Colonel Ellet’s ram fleet joined Davis’s ironclads on April 13, 1862, fifty miles above Memphis where Fort Pillow loomed atop steep bluffs with numerous batteries guarding the river approach. Meanwhile, General Halleck and his armies were advancing on Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard’s troops holed up in Corinth, Mississippi, less than a hundred miles to the east. Ellet visited Davis to obtain his views and offer cooperation, but as he reported to Stanton: “The commodore intimated an unwillingness to assume any risk at this time.”

Ellet proposed to immediately surprise and destroy the enemy’s gunboats, rams, and transports at Fort Pillow, and requested participation of one or more ironclads. Operating together, he suggested, they could interdict river supplies to Beauregard at Corinth, block potential water escape routes for fleeing Rebel forces, and expose Memphis. “To me, the risk is greater to lie here with my small guard and within an hour’s march of a strong encampment of the enemy, than to run by the batteries and make the attack.”[5]

Davis demurred. Relations were tense between the aggressive riverman and the cautious navy officer. Callender noted that Ellet “had come down there for a fight, and that he did not propose tying up to a tree and waiting for the fight to find him. The Colonel was a man of war and desired no one to forget it.”[6]

Davis, however, would relegate the rams to secondary roles: “It will be most expedient and proper that the [ironclad] gunboats should take the front rank in a naval engagement,” he informed Ellet. From the rear, the rams could exploit opportunities to attack the enemy’s flank, assail enemy stragglers, assist disabled friendly vessels, and capture disabled enemy craft.

Gunboats and rams “bear to each other the relation of heavy artillery and light skirmishers; to expose the latter to the first brunt and shock of battle would be to misapply their peculiar usefulness and mode of warfare.” The flag officer was most concerned that Ellet’s boats had no big guns; it would be “a matter of great mortification” should any be lost for lack of defensive capability.[7]

Ellet was having none of that tactic. His view was “to act as soon as possible, on the offensive.” While concurring in the necessity to avoid unnecessary exposure, he responded, “almost the only efficient service these rams can render is that for which they were specially built, viz, to run into the enemy, with good speed and head on, and sink him.” The ram fleet would proceed without ironclad support if necessary, Ellet wrote Stanton. “Delay will be fatal to the usefulness of this fleet.”[8]

Davis answered: “I decline taking any part in the expedition which you inform me you are preparing.” Then he raised the command question: “I would thank you to inform me how far you consider yourself under my authority.” Ellet regretted the flag officer’s indisposition to cooperate, but, “I do not consider myself at all under your authority.”

In the absence of plans for cooperation, Ellet would communicate his intentions and engage as he saw fit. “I do not understand that you are to be held in any way responsible for my operations, or are at liberty to interfere with them if they merely involve hazard to my own command.”[9]

On May 29, Beauregard abandoned Corinth before Halleck’s advancing legions rendering Fort Pillow untenable and Memphis indefensible. Flag Officer Davis moved downriver and at first light on June 6, 1862, formed his five ironclads in line abreast across the channel above Memphis; the Confederate River Defense Fleet steamed out to engage. Davis hoped Ellet’s rams would show up but had no idea where they were. As 6 a.m. approached, the show opened with a long-range gun dual.

Meanwhile, Col. Ellet had set out at dawn in his flagship Queen of the West followed by the Monarch with Lt. Col. Alfred Ellet in charge. Proceeding downriver, they spotted Davis’s boats strung across the stream and heard gunfire as a shot screamed overhead. Ellet hoisted the signal for action and shouted across to his brother: “It is a gun from the enemy! Follow me! Now is our chance.”[10]

To the surprise of both sides, Queen of the West and Monarch suddenly charged through the ironclad line and initiated a raging, confused melee with the Rebel rams as the ironclads joined in with their guns. Despite a total lack of coordination, the naval battle of Memphis resulted in complete Union victory, but it was the last time civilians commanded warcraft in combat. Read about what happened in a previous post: A Most Curious Battle: Memphis, June 6, 1862.

[1] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 29 vols. (Washington, DC, 1894-1921), Series 1, vol. 23, page 40. Hereafter cited as ORN. All references are to series 1.

[2] Ibid., 40-41.

[3] Ibid., 41.

[4] Eliot Callender, Speeches of a Veteran (Chicago: Blue Sky Press, 1901), unpaginated, 34th text page.

[5] ORN 23, pages 28, 29-30.

[6] Callender, Speeches, 34th-35th text page.

[7] ORN 23, pages 33-34.

[8] Ibid., 34, 36.

[9] Ibid., 39-40.

[10] Alfred W. Ellet, “Ellet and His Steam-Rams at Memphis” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, 4 vols. (New York, 1884-1888), vol. 1, page 456.

Excellent explanation of the confused command, control and application of waterborne forces which contested for supremacy on the inland waterways during the Civil War… overseen by the Army.

Great piece! This part of the war is so fascinating and yet so little known. I have a question: is there a complete registry of river and ocean-going ships in the war? I ask because my ancestor, a Federal private, notes in his diary, while being transported to the Peninsula in 1862, that his regiment went aboard the “Washington.” Searching what registries I could uncover, I found that we basically had no ships or steamers named “Washington” or “George Washington.” I seem to recall that at that time it was not considered decorous to name a ship after the Father of the Country. Furthermore, I learned there was a “George Washington Parke Custis,” but this was cut down to deck level to become our first aircraft carrier – it took Professor Lowe’s balloons to the Peninsula, and there was a single “George Washington,” but this was a steamer constructed and used on the western rivers, and was never in the east. I did find there was a “Washington Irving” that was pressed into service for the Peninsula Campaign – could this have been the one to which my ancestor referred?

There is no ONE reference that records all Civil War waterborne vessels. These are the ones that are proven to be the most helpful:

Civil War Shipwrecks, Encyclopedia (2008) at [archive org]

Riverboat Dave’s Mississippi River & Ohio River Steamboats at [paddlesteamers info]

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies Series No.2 Vol.1 [U.S. Navy warships pp.10- 247 and C.S. Navy vessels of war pp.247- 310] [HathiTrust]

List of Tinclad Warships of the U.S. Navy at [Wikipedia]

Contract steamers and vessels owned by Cornelius Vanderbilt, the American Collins Line, the United States Mail Steamship Company, Howland & Aspinwall, and the Pacific Mail Steamship Company (many of which carried cargo or troops for the U.S. Government) must be investigated through the companies that owned them [although local newspapers published in port cities often reported the arrival/ departure of vessels on their last page, for example, SS Baltic arrival/ departure could be found in New York City newspapers; those vessels that participated in McClellan’s voyage to the Peninsula may be found in District of Columbia newspapers, as many vessels set off from Alexandria Virginia.]

Zounds! Thank you, Mike, for all the information and suggestions. I shall pursue them. Perhaps…you should write the one reference to encompass all these vessels…? By the way, I believe the transport my ancestor took was the ‘Washington Irving.’ I’ve often wondered if he merely forgot the ‘Irving’ or if someone painted that out, making the steamer the ‘Washington’ for a while – and thus more patriotic… Again, much thanks!

While searching for something else… found record of steamer George Washington in the Rock Island Illinois Evening Argus of 4 JAN 1862 page 2 column 3 under dateline “Fort Monroe.” It appears to have been operating as a contract steamer between Fortress Monroe and Aiken’s Landing in the James River, acting as Flag of Truce boat for exchange of prisoners of war.

Wow, Michael, thank you so much for this!

You have to figure this was the one that shipped my ancestor’s regiment, he referring to it as ‘the Washington,’ a better choice than him calling the ‘Washington Irving’ the ‘Washington.’ The timing and location is right; when McCall’s division was taken from I Corps and sent to the Peninsula on 9 June 1862, they must have sent any steamers available. Any chance of finding a photo? It’s ironic – as I told you, I searched and searched and could not find any ship in the East named the ‘George Washington’ – and then you, the naval expert, found it when you weren’t looking for it, just as I found my ancestor’s diary.

Your kindness is so deeply appreciated. Please keep me advised. My email is epschafer@gmail.com. I’ll let you know when the book is released – you will get a big Thank You in the Acknowledgements. Happy Thanksgiving!

Upon investigation of “Riverboat Dave’s” site, found it has migrated: Steamboat Museum https://steamboats.com/museum/index.html

Eric: Thanks for the interesting question and thanks to Mike for the great suggestions. I have another one for you: The Army’s Navy Series, Volume II: Assault and Logistics, Union Army Coastal and River Operations 1861-1866 by Charles Dana Gibson (Ensign Press, 1995). Great book. Out of print but available used or you can view electronically for free at https://archive.org/details/assaultlogistics0000gibs. It has a good chapter on the Peninsula Campaign (p. 191). Unfortunately, it muddies the waters concerning the “Washington.” The only applicable index entry mentions that the “gunboat George Washington” was sunk in late 1863 (page 299). A gunboat was any boat with a gun, but they also could transport troops when needed so could be your boat. No “Washington Irving” is mentioned. There is a companion volume: Dictionary of Transports and Combatant Vessels, Steam and Sail Employed by the Union Army, 1861 – 1868 which is an index of almost 2,000 steam vessels. I don’t have that one but am ordering it. Good luck. Glad you enjoyed the post.

Eric: Reference the Dictionary of Transports and Combatant Vessels mentioned above, I finally received a copy. On page 132 is the following information:

GEORGE WASHINGTON; armed steam tug, converted to gunboat; 243 tons.

Chartered June 21-Sept 23, 1862; Oct 6, 1862, for unknown period. Participated as rescue vessel in naval action in Hampton Roads on Mar 10, 1862. May 1862 was employed James River – Hampton area of Virginia. Listed as tug assigned to Department of Virginia Oct 22, 1862, remaining in that assignment as per Army list of Mar 11, 1863. Engaged carrying elements of the 76th Pennsylvania Regiment during expedition from Port Royal, South Carolina, in Oct 1862, to a point upriver on the Broad River. On Apr 9, 1863, while participating in an expedition up the Coosaw River, South Carolina, she ran aground and immediately came under Confederate fire. At the time, the tug was under command of Captain Biggs, an artillery officer. Vessel was badly damaged. According to some sources, vessel was destroyed by rebels. A number of her crew were killed and wounded. Captain Biggs was censured for not having sufficient control of his crew.

[ORN, I, 7, 8, 13, 14; HR-337, Ocean, lake, p 106; Higginson]

Hope that helps.

Thank you so much, Dwight – so kind of you to send me this information.

Not knowing the configurations and space on a tug of 243 tons of that period, and as converted to a gunboat – are there photos? – I wonder, do you think it could have served as a transport? My ancestor writes in his diary that “we boarded the ‘Washington’ and are now comfortably quartered” – does that sound reasonable for a tug? Could it transport any appreciable number of soldiers?

Again, much thanks, and happy Thanksgiving!

I do believe that your photo depicts the U S S St. Louis, not the Carondelet. The give-away is the Masonic symbol between the stacks. Both constructed in Eads St. Louis shipyard, they are of course identical except in this one respect.