Two Paths to Heroism: Robert Blake, William Carney, and the Medal of Honor

ECW welcomes back guest author Walt Young.

Who was the first African American recipient of the Medal of Honor? Two African American men – one a soldier and one a sailor – each have claims to the distinction. The stories of Robert Blake and William Carney illustrate African Americans’ paths to freedom and valorous actions during the Civil War.

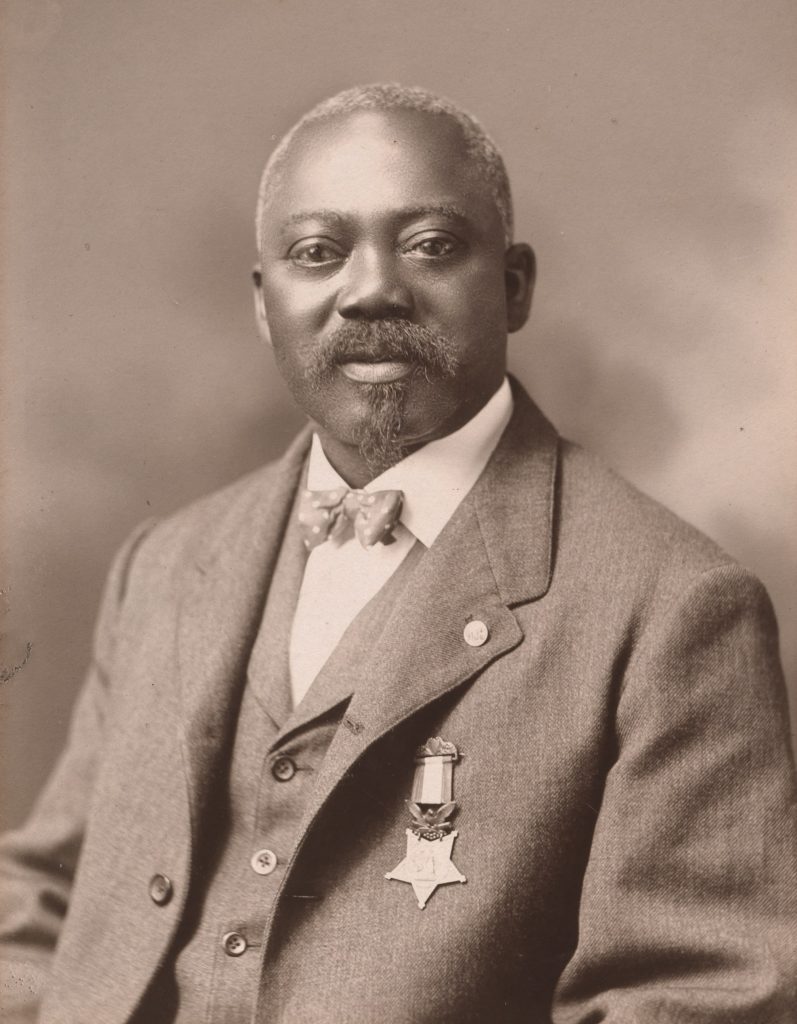

In part because of his regiment’s fame, many have heard of Sgt. Carney. Born into slavery in Virginia in 1840, Carney gained his freedom as a young man; his mother was manumitted along with her family, likely during the 1850s. Carney, by his own telling, learned to read and write at age 14 and moved with his family to Massachusetts. Despite the family’s free status, Carney gives an example of the fear of recapture, eventually telling The Liberator that his father “rested not” in Pennsylvania, as “the black man was not secure on the soil where the Declaration of Independence was written.”[1]

Carney enlisted in one of the first Black regiments in the country, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry. Their story is well known – after mustering in Massachusetts and training near Beaufort, South Carolina, the 54th was sent to Charleston Harbor in the summer of 1863. They participated in attacks on Morris Island, a barrier island just outside the harbor. In their assault on Confederate-held Fort Wagner, the 54th took heavy casualties: 270 of 650 men were killed, wounded, or captured, a 42-percent casualty rate. Men of the 54th would have known that capture could have deadly consequences, as Confederates took the idea of Black soldiers as a specific threat.[2]

The regiment did not take Fort Wagner that day, but Carney’s heroism helped the regiment reach their high-water mark. A correspondent for the New York Tribune gave an account of his actions, which appeared in papers across the nation:

“But above all, the color-bearer deserves more than a passing notice. Sergeant John Wall of Co. G carried the flag in the first battalion, and when near the fort he fell into a deep ditch, and called upon his guard to help him out. They could not stop for that, but Sergt. William H. Carney of Co. C caught the colors, carried them forward, and was the first man to plant the Stars and Stripes upon Fort Wagner. As he saw the men falling back, himself severely wounded in the breast, he brought the colors off, creeping on his knees, pressing his wound with one hand and with the other holding up the emblem of freedom…the brave and wounded standard-bearer said: ‘Boys, I did but my duty; the dear old flag never touched the ground.’”[3]

Carney’s story was publicized across the North, a potent symbol of the patriotism of African American troops. The abolitionist paper The Liberator, gave him space to tell the story of his earlier life, which gives us a valuable example of the background of an early Black soldier.

Carney mustered out of service as a sergeant by the end of 1864. In 1900, he received the Medal of Honor for his actions at Fort Wagner. His Medal of Honor citation reads as follows: “When the color sergeant was shot down, this soldier grasped the flag, led the way to the parapet, and planted the colors thereon. When the troops fell back he brought off the flag, under a fierce fire in which he was twice severely wounded.”[4]

The fact that Carney received his Medal of Honor well after the war likely contributes to his memory today. He was in the public eye as a veteran many years after his actions and is often cited as the first Black Medal of Honor winner. Our second subject, however, had his medal by the end of the war.

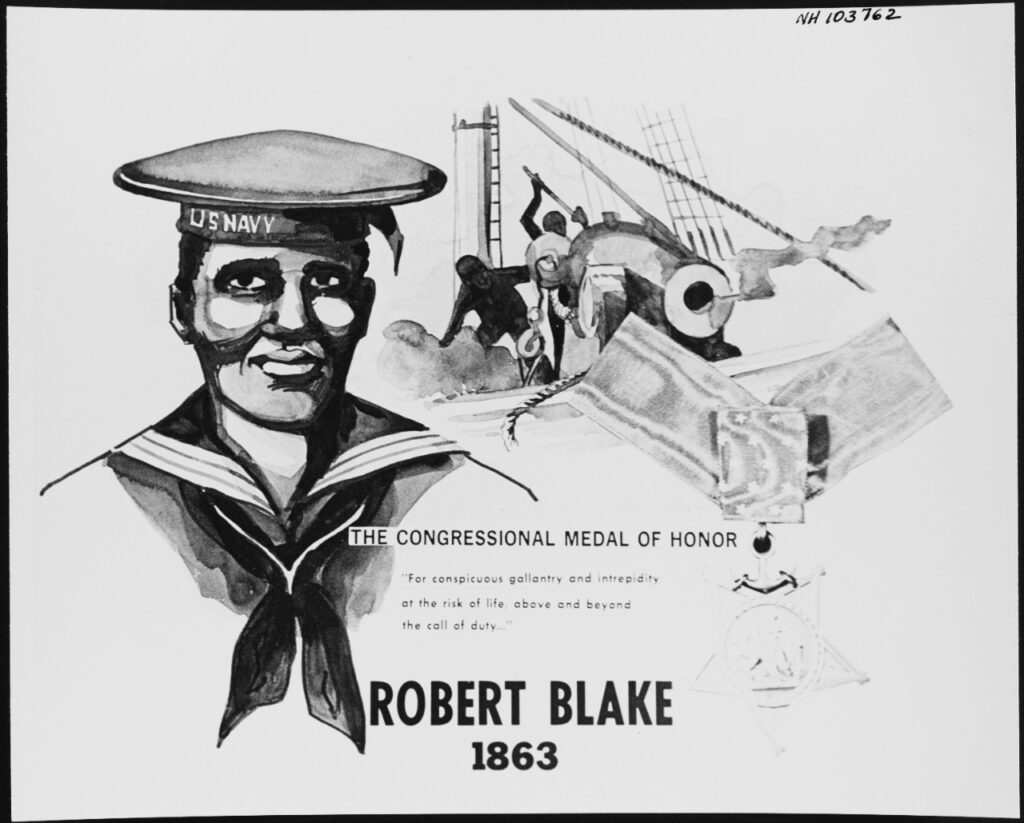

Much less is known about Robert Blake’s early life. Unlike Carney, however, we can state that he was still enslaved at the beginning of the Civil War. In early 1862, a Robert Blake, aged 28, was one of over 400 people enslaved by Arthur Blake, a plantation owner along the Santee River between Charleston and Georgetown, South Carolina. As the US Navy expanded its blockade, they made incursions along the coastline. Because Confederates used Blake’s plantation as a point to fire on US ships in the river, they captured the plantation on June 25, 1862. The 402 enslaved workers mentioned above managed to escape to US lines, seizing their opportunity for potential freedom. Robert Blake was probably among them.[5]

Like many escapees, Blake served in the navy as a sailor, and by Christmas of 1863 he was serving on USS Marblehead. Like Carney, his valorous act would take place on the outskirts of Charleston, South Carolina.

In the months after the 54th Massachusetts attacked Fort Wagner, United States forces gained a foothold on Morris Island. From there, they began an artillery bombardment of Charleston’s forts and city, lasting intermittently until February 1865. Despite the bombardment, the Confederates maintained a hold on Forts Sumter and Moultrie, and the campaign to take back the city saw many false starts over the next year and a half.[6]

One potential side route into the city lay from the south and west, through narrower channels such as the Stono River. On the morning of December 25, 1863, USS Marblehead was patrolling along the Stono. It was near Legareville, the furthest US outpost up the river, approximately eight miles from the city of Charleston.[7]

This Christmas morning, the only present that Marblehead’s sailors received was a surprise bombardment by Confederate artillery. According to an official account from the Department of the South’s nearby headquarters, the Confederates hoped to sink the vessel and take the outpost. According to the account:

“The Confederates fired upwards of three hundred rifled projectiles at the Marblehead, and it is most extraordinary that she escaped total destruction. She in return fired two hundred and fifty-six shell and shrapnel, nearly all of which fell into the midst of the enemy … the loss on the Marblehead was three killed (cut in two literally), and four wounded seriously … the courage and heroism of the gallant officers and crew of the Marblehead is beyond all praise. They fought with great odds against them, and achieved a splendid victory.”[8]

Robert Blake survived the victory and proved his personal mettle in the process. In an early account of the battle, his story is specifically mentioned: “…with Robert Blake, a contraband, of whom it is said, he ‘excelled my admiration by the cool and brave manner in which he served the rifle gun.’”[9]

Blake’s heroic acts came after Carney’s service at the battle of Fort Wagner. However, Blake was officially honored much more quickly. In mid-April 1864, he became the first African American man to receive his Medal of Honor. His citation reads:

“The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Contraband Robert Blake, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving on board the U.S. Steam Gunboat Marblehead off Legareville, Stono River, 25 December 1863, in an engagement with the enemy on John’s Island, South Carolina. Serving the rifle gun, Contraband Blake, an escaped slave, carried out his duties bravely throughout the engagement which resulted in the enemy’s abandonment of positions, leaving a caisson and one gun behind.”[10]

Unlike Carney, Blake’s later life is unknown, including his date of death. Ironically, his reception of the Medal of Honor so soon after his heroism likely meant that there was no renewed cycle of news coverage or interest in him in the early 1900s, as there was with Carney.

For some African Americans, joining a Civil War regiment was a choice made years after gaining freedom; for others, the US military was an immediate lifeline out of a life of bondage. Whatever path one took to the military, Black soldiers and sailors served with recognition across the nation. These two Medals of Honor, both earned within miles of the war’s first battle site, illustrated the bravery of Black soldiers and sailors in combat – and helped prove that fact to the nation.

Walt Young has loved learning about the Civil War since visiting Harpers Ferry, West Virginia on a childhood trip. When not studying history, he enjoys hikes, mysteries, and Baltimore sports.

Endnotes:

[1] “Interesting Correspondence,” The Liberator, November 6, 1863.

[2] “54th Massachusetts Regiment,” January 4, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/articles/54th-massachusetts-regiment.htm, accessed August 21, 2024. Fort Wagner and Battery Wagner are often used interchangeably.

[3] “Conduct of the Mass. Fifty-Fourth at Fort Wagner,” Boston Evening Transcript, August 4, 1863.

[4] William H. Carney, 54th Massachusetts, Organization Index to Pension Files of Veterans Who Served Between 1861 and 1900, compiled 1949 – 1949, documenting the period 1861 – 1942, Roll 223, T289, Records Group 15, US National Archives; “William Carney,” National Medal of Honor Museum, 2023, https://mohmuseum.org/medal_of_honor/william-carney/, accessed August 24, 2024.

[5] “Whatever Happened to Robert Blake and the Battle of Lagareville, SC,” A Civil War Traveler, January 5, 2024, https://civilwartraveler.blog/2024/01/05/whatever-happened-to-robert-blake-and-the-battle-of-legareville/, accessed August 21, 2024; “United States General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934,” International African American Museum, January 27, 2020, https://iaamuseum.org/center-for-family-history/blog/united-states-general-index-to-pension-files-1861-1934/, accessed August 21, 2024; Arthur Blake, South Carolina, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, compiled 1874 – 1899, documenting the period 1861 – 1865, M346, Records Group 109, US National Archives.

[6] Mark Maloy, “Charleston during the Civil War: Lighting the Fuse of America’s Bloodiest War,” American Battlefield Trust, 2024 April 19, 2024, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/charleston-during-civil-war, accessed August 29, 2024.

[7] “Legareville,” John’s Island Conservancy, November 24, 2012, https://jicsc.org/index.php/legareville/, accessed August 29, 2024.

[8] “Department of the South” The Sunbury Gazette, and Northumberland County Republican, January 9, 1864.

[9] “Naval Engagement Near Charleston,” The National Republican, January 4, 1864.

[10] “Robert Blake,” The Hall of Valor Project, 2024, https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/2698, accessed August 29, 2024.