Fine Dining, POW Style: Johnson’s Island Rat Club

ECW welcomes back guest author Kevin C. Donovan.

Aficionados of classic 1960s TV may remember The Rat Patrol, which thrilled its audience with the exploits of “desert rats,” Allied soldiers roaming the North African desert in World War II. A century before that fictional drama, the Civil War exploits of another “rat patrol” similarly thrilled its audience. But while this earlier group also featured roaming soldiers, the stars of the show were not “desert” rats, but “wharf” rats. And the enemy was not Germans, but hunger. This is the story of how starving men came to form the Johnson’s Island “Rat Club.”

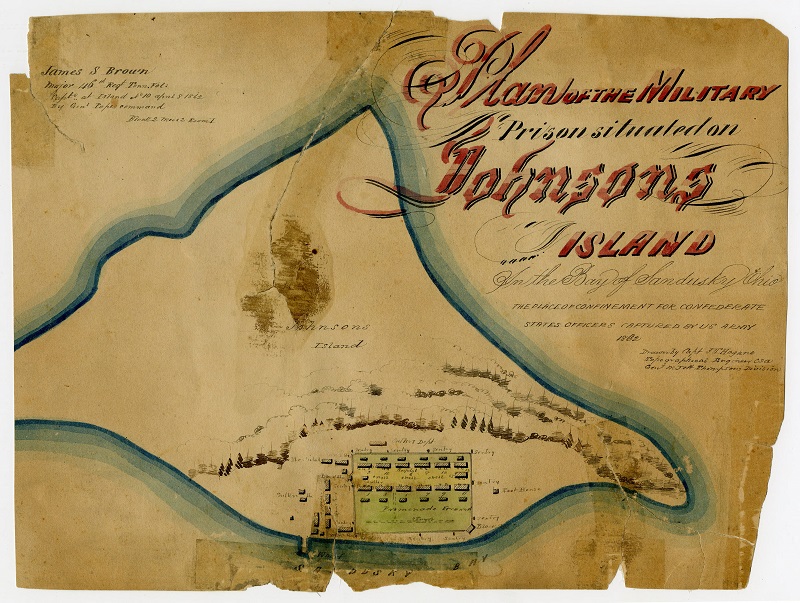

Johnson’s Island, on Lake Erie near Sandusky, Ohio, was a prisoner-of-war camp for Confederate officers. Conditions were relatively humane for much of its operation, shown by the fact that only 241—about 2 percent—of prisoners perished (Andersonville’s mortality rate was 29 percent).[1]

But the place was hardly idyllic, particularly concerning the subject of food. As one author explained: “The living conditions can be divided into two distinct periods. During one of these periods the Rebels had abundant provisions and were almost happy in their confinement. During the other period the Rebels were underfed constantly.”[2]

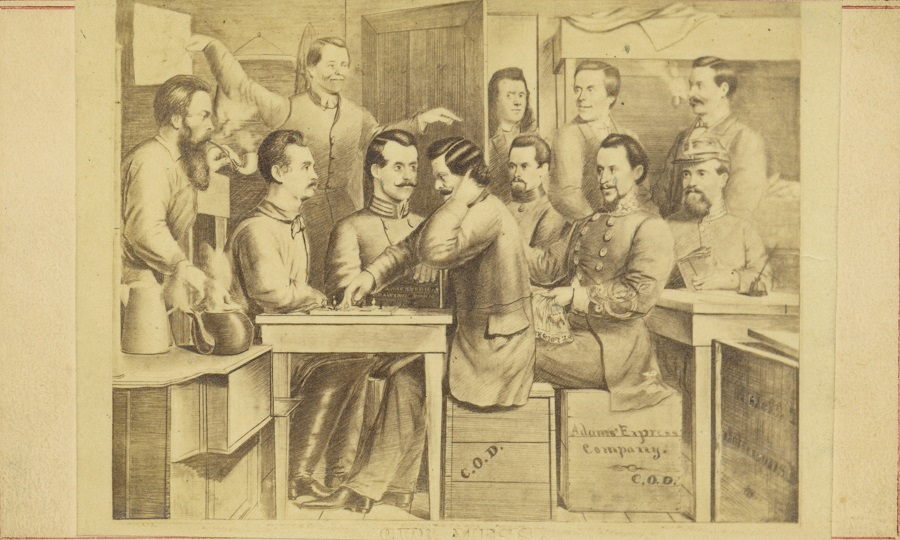

As one ex-POW described that first period, “It was not heaven, but as yet it did not represent the other extreme.”[3] The POW ration was identical in amount to the guards. The prisoners could supplement their diet by buying from sutlers luxuries such as “canned fruit, sardines, and fresh fruit when in season.” Aid packages from home also helped make food “abundant.” Indeed, some Confederates surely dined better than when they were in active service.[4]

The bounty ended with the dawning of 1864. The impetus was reports of suffering endured by U.S. prisoners held by the Confederacy.[5] Regardless of the justification, action resulted.

First, the sutlers were closed to all but the sick. Worse, the daily ration was reduced. One POW recalled receiving only a “loaf of bread and a small piece of fresh meat,” not sufficient to stave off constant hunger pangs.[6] That inmate’s routine was to eat half the loaf and the scanty meat for dinner, finishing the bread as evening supper. He then “breakfasted with Duke Humphrey” (i.e., went without food).[7]

In July 1864, the situation worsened. The ration was further reduced. Restrictions on supplemental food sources tightened. The sutler now was forbidden to sell food to any prisoner, even the sick. Outside food packages ceased. Only the very sick who obtained specific permission were excepted. This last order resulted in heartbreak for prisoners learning that food had been sent, but withheld because of no advance permit. One POW ended up with only a toothbrush from a package from home. Another prisoner was given “only the empty box,” which had contained “some choice North Carolina hams.”[8]

The worst experience certainly was that of Capt. Wesley Makely, whose wife’s letter dutifully listed all the delicacies sent him, including a turkey, ham, oysters, cakes, biscuits, nuts, sugar, coffee, assorted fruits, and “gum drops.” Makely did not even get the gum drops.[9]

The inmates suffered in body and spirit from the lack of adequate food, with many displaying a “far-away look in their eyes and with hunger and privation showing in every line of their emaciated bodies.”[10] Some lost their hair; others went prematurely gray. Prisoners rummaged through garbage heaps while futilely looking for scraps. The malnourished filled the hospital.[11] Desperate times called for desperate measures. The local rat population was eyed, and what had been a thriving community soon fell victim to human hunger.

Actually, the first recorded culinary experimentation in this field was in February 1864, probably before the effects of policy changes would have made necessity the mother of rodent digestion. One prisoner just wanted to know what wharf rat tasted like; the answer: “squirrel.”[12]

That incident was the result of one inmate’s curiosity. As conditions deteriorated, however, more prisoners determined that they must turn to the rats to supplement their meager diet. But, mindful of the adage that the “first step in cooking rabbit stew is catching the rabbit,” the prisoners first took organized steps to catch their quarry.[13] Thus was born the Rat Club.

The Rat Club was a hunting party. Its goal was simple: “catch as many of the huge wharf rats as possible each day.” The rats then were invited to dinner, serving as honored, edible guests. Others not of the mess could purchase a rat dinner. The going price was ten cents a rat.[14]

Some had to pay for the privilege of a mealtime rodent guest due to an absence of the skill exhibited by the dedicated hunters. One POW woefully recounted in a post-war account that despite his best efforts, he had been unable ever to procure a rat dinner. He noted that “a dog would have served the purpose better” for rat-hunting, except that “the chances were that some hungry ‘Reb’ would have eaten the dog.”[15] In fact, for a time there was a female terrier named Nellie who was skilled at rat catching. Nellie even survived long enough to give birth to four puppies, who the inmates hoped would grow up to become prime rodent retrievers.[16]

At first, the sheer number of the rodents favored the Rat Club’s efforts. However, just as any over-hunting leads to scarcity, so, too, did the “rat patrol” face a challenge after a time. In a post-war account, Col. Benjamin W. Johnson, commander of the 15th Arkansas, observed the impact of the rat patrol on their fellow camp residents: “At the time [the] reduction in rations took place I suppose that the prison had the largest and happiest army of rats on the face of the earth. Great, big, fat fellows, who had been rolling in luxury on crusts and bones. But soon they began to disappear. They never deserted, nor were they ever paroled, but they never regained their liberty.”[17]

As the rat population was thinned, the intrepid hunters altered tactics, and “organized themselves into squads and deployed themselves as skirmishers, each one armed with a club, as they marched … in search of rats.”[18] The rat patrol’s renewed efforts bore fruit. Its prey continued to grace POWs’ plates. One noted in a February 19, 1865, diary entry that rats were still being caught, although he had not succumbed to the temptation to share in the bounty, writing “I choose rather to suffer … than resort to such food.”[19]

Meanwhile, the POWs’ pleas for more food not only were ignored, but rations were further reduced on February 1, 1865. The only concession was that sutlers now could sell POWs “vegetables in such quantities as may be necessary to their health.”[20]

Fortunately, by then the end of the POWs’ suffering on Johnson’s Island was in sight. But for many, the efforts of a roving band had mitigated their hunger. Whatever one thinks of serving up wharf rat, squirrel-tasting or not, the “rat patrol” had served its comrades well.

Kevin C. Donovan, Esq., a retired lawyer, now focuses on Civil War research and writing, including on law-related topics such as “How the Civil War Continues to Affect the Law,” published in Litigation, The Journal of the Section of Litigation, of the American Bar Association. His inaugural ECW blog publication, “A Tale of Two Tombstones,” appeared December 9, 2022 and was ECW’s most popular post of the year on social media. The author’s wife’s great-grandfather, Captain Matthew John Lucas Hoye (39th Mississippi), was a POW on Johnson’s Island.

Endnotes:

[1] Charles R. Schultz, The Conditions At Johnson’s Island Prison During the Civil War, Unpublished Master’s Thesis (Bowling Green University, January 1960), https://etd.ohiolink.edu/acprod/odb_etd/ws/send_file/send?accession=bgsu1670398956769758&disposition=inline; James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 802.

[2] Schultz, 23.

[3] Horace Carpenter, “Plain Living at Johnson’s Island,” Century Magazine, (March 1891), Vol. 41, 705, 714.

[4] Schultz, 47-51, 67 & n. 57, 89-90; Johnson’s Island Preservation Society, Island History – Civil War Era, Prisoner of War Depot – Overview, Depot Prisoners of War, Near Sandusky, Ohio, pp. 47-51, http://johnsonsisland.org/history-pows/civil-war-era/; Carpenter, 705, 714.

[5] Roger Pickenpaugh, Johnson’s Island: A Prison for Confederate Officers (Kent, OH, Kent State University Press, 2016), 80-81.

[6] Carpenter, 705, 714-715; Schultz, 88 & n. 1, 90, Appendix G, for all the changes in rations.

[7] Carpenter, 705, 715.

[8] Schultz, 90, 92-100, 102.

[9] David R. Bush, I Fear I Shall Never Leave This Island: Life in a Civil War Prison (Gainesville, FL, University of Florida Press, 2011), 161-163.

[10] Carpenter, 705, 715.

[11] Schultz, 91, 97, 100, 106; Carpenter, 705, 715.

[12] Schultz, 108 & n. 47.

[13] Isaac Asimov, “Catch That Rabbit,” I, Robot, (Greenwich, CT, Fawcett Publications, Inc., 1950), 69.

[14] Schultz, 109-110.

[15] Carpenter, 705, 715.

[16] Schultz, 109-110.

[17] Ibid, 109; B. W. Johnson, “Record of Privation In Prison,” Confederate Veteran, (April 1901), Vol. 9, No. 4, 165.

[18] Schultz, 109-110.

[19] William B. Gowen, Diary of Lieutenant W. B. Gowen, CSA, 1863-1865, quoted in, Bush, 234.

[20] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of The Official Records of The Union and Confederate Armies, Series II, Vol. 7, 1021-1022, Vol. 8, p. 215; Schultz, 101-103, 107, 111.

Being from Northeast Ohio and having visited Johnson’s Island numerous times, I found your article about the “rat patrols” very interesting. Thank you for a great article.

I will never understand how any human being could treat these men in the shameful way they did. You may have won the war but you lost any kind of decency as a man. God bless the South.