Southern Redemption: How Former Confederates Dismantled Reconstruction

ECW welcomes back guest author Joseph D. Ricci.

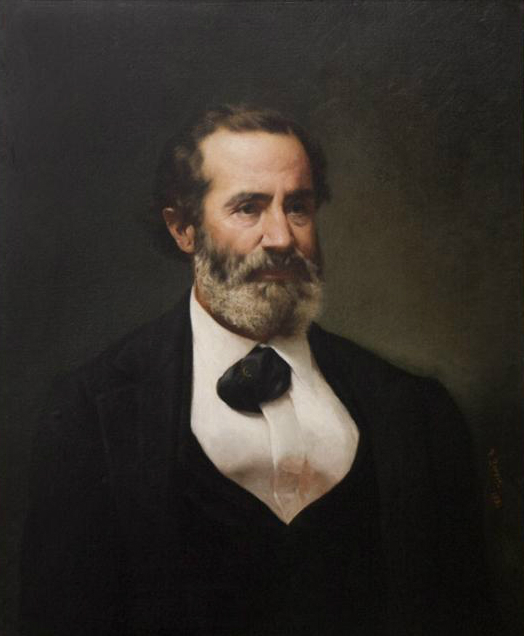

Jean Maximilien Alcibiades Derneville DeBlanc served as captain of Company C, 8th Louisiana Infantry when it was raised at Camp Moore in 1861. For three years, DeBlanc fought in Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. After the battle of Gettysburg, he assumed command of the regiment and was wounded. He returned to Louisiana in 1864 and led reserve troops in Natchitoches. In June of 1865, DeBlanc surrendered to Federal authorities. His war was over. The Confederacy had failed, and Reconstruction policies began to take shape in the former rebellious states. By December 1865, the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery was ratified and, within two years, citizenship was granted to African Americans. White Southern rule came to an end, for the time being. But on Christmas Day 1868, President Andrew Johnson started the nation down a difficult path:

“Now, therefore, be it known that I, Andrew Johnson President of the United States, by virtue of the power and authority in me vested by the Constitution and in the name of the sovereign people of the United States, do hereby proclaim and declare unconditionally and without reservation, to all and to every person who, directly or indirectly, participated in the late insurrection or rebellion a full pardon and amnesty for the offense of treason against the United States or of adhering to their enemies during the late civil war, with restoration of all rights, privileges, and immunities under the Constitution and the laws which have been made in pursuance thereof.”

With Johnson’s Amnesty Proclamation, DeBlanc and thousands of other disenfranchised former Confederates had a path to reclaim political agency. Still, it would be another four years before congressional action removed “all political disabilities” and allowed one-time Rebels to hold public office again. For Alcibiades DeBlanc, however, the path to power came through other means.

In July 1865, DeBlanc wrote, “The cause of the Confederate States, a just and a sacred cause, has been defeated.” Disgruntled with the post-Emancipation South, DeBlanc set his pen to the page, “I am fully aware that among many, we, slave owners, are considered as tyrants, and our slaves, as our victims; many again would be willing to extend to those pretended victims of our tyranny, those privileges which everywhere are denied to the white laborer and denied even to the soldier who has fought under the banner of his country.” He concluded, “Our misfortune is our crime- our treason…No! There is nothing of the past that I would repudiate….” DeBlanc, like so many other former Confederates, found themselves disillusioned with the outcome of the war and the upending of the slave-based agrarian society that perished with their defeat. As early as December 25, 1865, white paramilitary organizations formed to resist Reconstruction efforts.[1]

On May 22, 1867, DeBlanc organized and commanded the Knights of the White Camelia. Like the Ku Klux Klan, their goal was to restore the Democratic Party to power in the state and reassert white rule. The influence of DeBlanc and his Knights on the results of the presidential election of 1868 cannot be overstated. Through violent intimidation tactics carried out against blacks and Republicans, the Knights of the White Camelia guaranteed the election of Democrat Horatio Seymour. Their tactics though, were too successful, and the attention drawn to election fraud and terrorism resulted in the election being overturned by the State Returning Board. With that, DeBlanc’s Knights ceased to exist in any substantial numbers. Before long, DeBlanc found membership in the White League and rose in prominence in its ranks.

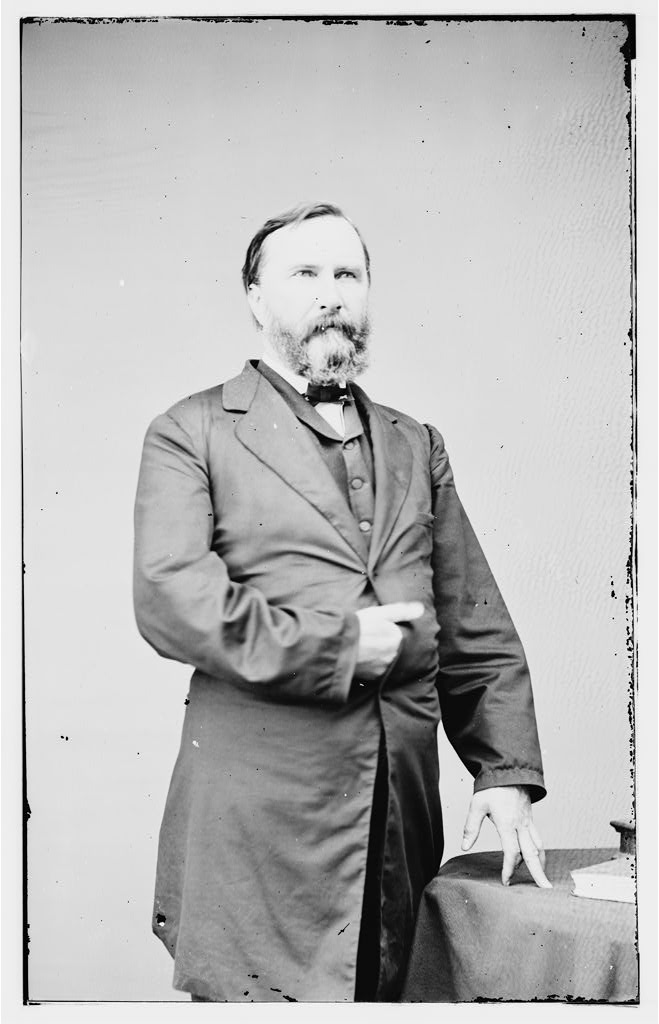

In 1874, a tumultuous gubernatorial election in Louisiana led to violence. In a bitter contest, William Kellogg, a Republican, defeated the Democrat, John McEnery. Kellogg’s election was contested by the White League. On September 14, 5,000 members of the White League, including 600 men commanded by DeBlanc, descended upon the city of New Orleans to install McEnery as governor and Davidson Penn as lieutenant governor. White Leaguers encountered resistance from the Louisiana State Militia and the integrated Metropolitan Police Force, led by former Confederate general, turned Republican and proponent of Reconstruction, James Longstreet.

Gunfire erupted on Canal Street. Longstreet advanced to meet the White Leaguers, but was shot and pulled from his horse. Removed from the fight and nursing an old war wound that had been reinjured, Longstreet watched as the Metropolitan Police were forced into full retreat. The morning after their successful “Canal Street Coup,” the White Leaguers arrived at Penn’s home, and given that McEnery was away, installed the former as the acting governor.

Reconstruction in Louisiana seemed to be careening toward a bloody end until Federal forces under the command of Maj. Gen. William H. Emory arrived and thwarted the White League. By October, Brig. Gen. Regis De Trobriand arrived with more Federal troops to secure the city. In the aftermath of the battle of Liberty Place, Longstreet and his family left the city for Gainesville, Georgia, Kellogg took his seat as the duly elected governor, Reconstruction continued, and DeBlanc remained a steadfast opponent to it. For his part in the battle of Liberty Place, DeBlanc was jailed, but never formally charged. Three years later, following the election of Governor Francis T. Nicholls, another former Confederate, DeBlanc, the “King of Cadiens,” was named to the Louisiana Supreme Court.[2]

In the Reconstruction South, one could easily follow the lead of a man like DeBlanc, and thousands did. This road was made even easier by the U.S. Congress. Passed on May 22, 1872, the Amnesty Act of 1872 removed the “political disabilities” to former Confederates with very few exceptions. Across the South, one-time leaders of the rebellion and other Confederate veterans became governors, congressmen, and judicial officials.

By 1877, after a hiatus in Mexico and later England, Isham G. Harris, a vehement supporter of secession and Confederate wartime governor of Tennessee, was elected to the U.S. Senate. Georgia sent John B. Gordon, who was one of Lee’s most trusted lieutenants, a fierce opponent to Reconstruction, and prominent member of the Ku Klux Klan, to the Senate as well. In South Carolina, Wade Hampton’s “Red Shirts,” like DeBlanc’s Knights, waged a guerilla war against Republicans, African Americans, and Federal soldiers. By 1876, Hampton ran for governor in a violent, hotly contested election and after months of uncertainty was declared the winner. Even the vice president of the Confederacy, Alexander Stephens, returned to Congress representing Georgia.

These “Redeemers,” as they dubbed themselves, fought a “campaign of political violence” and advocated for the “defiance of the national government.” “The name,” Lemann asserts, “implied a divine sanction for the retaking of authority the whites had lost in the Civil War.” It also ushered in “the reestablishment of white supremacy in the post-Reconstruction South.” Though they lost the war, from their offices at all levels of government, former Confederates ensured they would win the peace.

Their victory came at the expense of formerly enslaved populations. In his study of Reconstruction, W.E.B. DuBois determined, “The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.” By 1877, Reconstruction was ended, Federal troops were withdrawn from the South, black officeholders were slowly but surely removed from their elected positions, and Redeemers worked to enact Anti-Enticement Laws, or Vagrancy Acts, to further disenfranchise African Americans. Their efforts gave birth to the Jim Crow Era and the laws of segregation that dominated the nation well into the next century.[3]

While the Redeemers undermined Reconstruction and threatened the security of the republic, other former Confederates attempted to make good on their amnesty. Perhaps the best known of these prominent former Rebels turned model citizens was James Longstreet. Only behind Robert E. Lee, Longstreet was the most senior Confederate military leader by the end of the war, which made it more shocking when he became a Republican and voice for the advancement of Reconstruction era policies.

A “scalawag” and “traitor” to many of his longtime friends, Longstreet worked tirelessly to combat the Klan and other attacks on the Reconstruction government. He urged Southern whites to become Republicans and to take up their roles as the dominant force to shape the future of the former Confederacy.

Longstreet continued to be a leading Southern figure in post-war Republican politics into the next century. Though never an advocate of racial equality, Longstreet’s evolution from ardent Confederate to outspoken Republican symbolized the possibilities of Reconstruction. Recent biographer of Longstreet, Elizabeth Varon concludes, “Longstreet’s story is a reminder that the arc of history is sometimes bent by those who had the courage to change their convictions.” Longstreet succeeded in his personal reconstruction, but both he and the rest of the nation watched as the effort died and the Jim Crow Era was born.[4]

Reconstruction failed because as a nation, the people allowed it to fail. Its failure came at the expense of the American republic, the free but disenfranchised African American populace, and the future of the nation. For nearly a century, Civil Rights advocates, clergy, elected officials, and ordinary citizens struggled to finally secure the promises of Reconstruction. Great tasks remain before us in safeguarding the “government of the people, by the people, and for the people.” Three years after the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1965, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke to the challenge ahead for the future, “I say to you that our goal is freedom, and I believe we are going to get there because however much she strays away from it, the goal of America is freedom.”[5]

A version of this story appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of the Battle of Franklin Trust’s The Dispatch Magazine.

Endnotes:

[1] Jean Maximilien Alcibiades Derneville DeBlanc, New Orleans Tribune, July 21, 1865.

[2] “From St. Martinsville,” New Orleans Republican. August 30, 1874. 1.

[3] Lemann, Redemption. 185.

[4] Elizabeth Varon, Longstreet: The Confederate General Who Defied the South. (Simon & Schuster: NY, 2023), 363.

[5] Martin Luther King Jr., “Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution.” https://www.du.edu/equity/black-community-initiatives-rev-dr-martin-luther-king-jr-day#:~:text=I%20say%20to%20you%20that,Martin%20Luther%20King%2C%20Jr.

The North sold out to get votes for Rutherford B Hayes. William A. Dunning’s book “Reconstruction, Political and Economic, 1865-1877” has the details; many others have written about it. Also useful to read “The Prostrate State: South Carolina Under Negro Rule”, James Shepherd Pike. For the record, Dunning was from New York, Columbia University, and Pike was from Maine. Economic repression of an entire section of the country for 100+ didn’t work out well.

Alas, the Dunning School has done more harm to the way we remember the Civil War and Reconstruction than nearly anyone since Jubal Early.

The Rutherford B. Hayes election was the end of Reconstruction; William A. Dunning’s “Reconstruction, Political and Economic, 1865-1877” has a very good analysis of this. Another good analysis of that general financial history is “The Prostrate State: South Carolina ….” during Reconstruction, with relevant data. Neither author was from the South; Dunning was a Professor at Columbia, NYC, and Pike was from Maine.

So far, two attempted comments are still being submitted. Same message; comment on Hayes election in 1877.

“Reconstruction failed because as a nation, the people allowed it to fail. Its failure came at the expense of the American republic, the free but disenfranchised African American populace, and the future of the nation.”

I have concluded that it was never going to work because both sections were white supremacist, there were other priorities (western conquest, panic of 1873, tariff, etc.), and because it was attempted less to help freedmen and more to help Republicans and punish white Southerners. Also the North was more interested in reunion than racial justice. As such Reconstruction was a brief experiment that failed its first major stress test. It would not be until after World War II that Americans were ready to to try something like it again.

I have recently done a little reading on Reconstruction and have began to see it as something very different than I used to. If you look at what the Radical Republicans were doing it was actual nation building. Just like one would do to a conquered nation. However, I am not sure even the radicals saw it as such or realized that was what they were doing. Since the “conquered nation” was actually made up of American states it really muddies the waters. We were trying to bring democracy to a part of the country that actually never had it. I am struck by how similar the failures of Reconstruction are to other post war endeavors say like Vietnam or Afghanistan. Situations where we propped up “American Democracy” but then we left the job incomplete and the whole thing collapses as soon as we leave.