Echoes of Reconstruction: Misunderstanding About the “Black Codes”

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome back Patrick Young, author of The Reconstruction Era blog

A misconception I run into when I discuss Reconstruction is that the Black Codes were passed because of the corruption and mismanagement of the governments elected by new Black electors after the Civil War ended. White voters put the Black Codes in to prevent that corruption from happening again, under this misunderstanding of history. This is fully false.

Now let us be clear, there was virtually no Black voting before 1867 in the former Confederate states, and voting was not really extended to large numbers of Blacks until 1868. White resistance was still so strong even after 1868 that the 15th Amendment removing the color bar on voting had to be ratified in 1870.

The Black Codes were passed by all-white Southern legislatures elected by all-white voters beginning in fall 1865. Many of those voting for the Black Codes were people associated with the Confederacy, either as soldiers or politicians or as civilian supporters. The voters in these elections were not responding to Black misrule; they were trying to maintain white supremacy from the close of the Civil War onward. The voters and their representatives wanted to use the power of their state governments to use the force of the state to segregate African Americans, cut them off from the benefits of citizenship, and, using police powers, stop Black labor organizing.

President Andrew Johnson remarkably left state and local governments in the hands of many of the same white men who had led the South into rebellion against the United States. These men excluded Blacks, including Black Union veterans, from voting, and the all-white post-war legislatures passed laws called the Black Codes that severely restricted the rights of the newly freed slaves. The statutory framework for continuing white rule were the Black Codes.

The former Confederates were so powerful that in 1866 Alexander Stephens, the former vice president of the Confederacy, was elected by the all-white Georgia legislature to the United States Senate.

The white legislators in the various Confederate states, rather than rebuilding their infrastructure which both the Union and Confederate armies had destroyed, providing health care for wounded Confederate soldiers, or providing for the incorporation of the newly freed formerly enslaved people into the free labor economy, instead passed the Black Codes.

In fall 1865 a Black convention met in Charleston’s Zion Church in South Carolina and issued this critique of the Black Codes:

“Without any rational cause or provocation on our part, of which we are conscious, as a people, we, by the action of your Convention and Legislature, have been virtually, and with few exceptions excluded from, first, the rights of citizenship, which you cheerfully accord to strangers, but deny to us who have been born and reared in your midst, who were faithful while your greatest trials were upon you, and have done nothing since to merit your disapprobation.

We are denied the right of giving our testimony in like manner with that of our white fellow-citizens, in the courts of the State, by which our persons and property are subject to every species of violence, insult and fraud without redress.

We are also by the present laws, not only denied the right of citizenship, the inestimable right of voting for those who rule over us in the land of our birth, but by the so-called Black Code we are deprived the rights of the meanest profligate in the country—the right to engage in any legitimate business free from any restraints, save those which govern all other citizens of this State.”

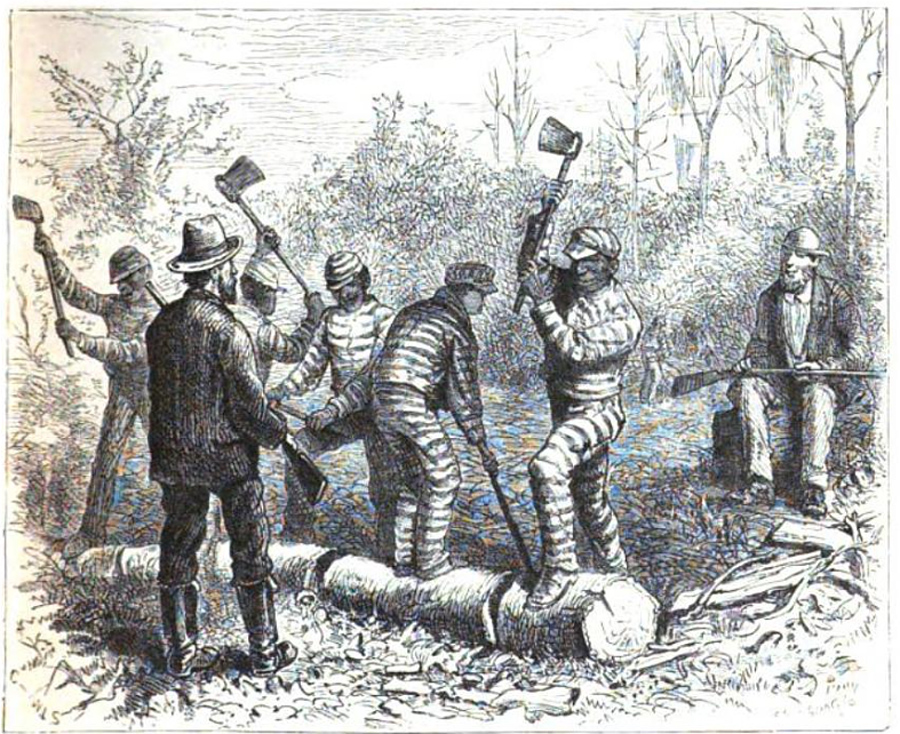

The Black Codes provided for re-enslaving Blacks without calling them slaves. So, under the 1865 Black Code in Mississippi, Blacks who owed debts to their county or the state could be arrested and sold to white men until their debt was paid off. The Black Codes also set up an expensive set of penalties for Blacks, which meant that it would be virtually impossible to go through the year without being arrested and sold. For example, if a sheriff found a Black man without proof that he was working, he could arrest the Black man and fine him $150, about $3,000 in today’s money. If the unemployed man did not have that amount, he could be sold on the courthouse steps.

If Mississippi Blacks held a meeting to inform the community about this law, everyone could be arrested and fined $150 dollars, except for whites attending an interracial meeting in which the white people would be fined $200 to prevent interracial political action.

Under the Black Codes, illiterate Blacks were obliged to sign contracts that they could not read or else risk arrest for vagrancy. If a Black left his job, the sheriffs could arrest him or her and carry them back to their employer. And these were not short-term labor contracts. In most cases the term was twelve months or more.

When we hear of the rise of the Radical Republicans, this “rise” did not happen before the end of the Civil War. There were advocates like Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass and key people in the Federal legislature who were Radical, meaning that they wanted equal Civil Rights regardless of color. But most Republicans were not Radical, nor were most voters in the North. It was only the advent of the Black Codes and the extrajudicial terror unleashed on Black communities in 1865 and 1866 that led Congress to, for the first time, seek the passage of Civil Rights Legislation.

When I was in law school a third of a century ago, I was examining the Civil Rights Act of 1866. I thought it was Section 1866 of the US Code, but I found out it was passed in 1866! It was a progressive piece of legislation that declared that anyone born in the United States was a citizen, and that under law Blacks would be treated the same as whites, except for voting. This act was not proposed in 1865 because many Northerners assumed that after the Confederate defeat, Southern whites would accommodate their Black fellow citizens. The Black Codes were the rejoinder to this hopeful expectation.

While Lincoln’s Attorney General Edward Bates wrote in a memo that, contrary to the Dred Scott Decision, Blacks might be U.S. Citizens under the Constitution, the 1866 Civil Rights Act was the first formal law that recognized that Blacks were citizens. That did not mean they had the right to vote. White women were citizens in 1866, too, and they did not have the right to vote. If you know children today can be citizens, but still not have the right to vote. While we often see voting as a key component of citizenship, you still have rights even though you can’t vote. For example, if Blacks were not citizens, they could be deported. So the Civil Rights Act of 1866 was radical, but not too radical!

Andrew Johnson vetoed the Civil Rights Act, but Congress overrode his veto.

The same coalition of Radical and moderate Republicans passed the 14th Amendment in 1866, and it was ratified by the states in 1868 after a long series of massacres in the South convinced Northern voters that untold horrors awaited the freedpeople without further protection. Part of the evidence that convinced Northern voters were the Black Codes.

As usual, an excellent commentary from Patrick Young. What Patrick calls a “misunderstanding” of the Black Codes resulted from the deliberate re-writing of history by Lost Cause historians trying to justify the overthrow of the democratic safeguards of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the 14th Amendment, both of which a family member of mine, Congressman George Boutwell, had a direct role in writing and enacting, as I describe in BOUTWELL: Radical Republican and Champion of Democracy, being released January 21 by WW Norton.

Thanks.

hi Pat. Could you drop me an email – to boutwell@alum.mit.edu. I’d like to get your advice on book talk and book review possibilities for my biography of George Boutwell being published by WW Norton on Jan. 21: BOUTWELL: Radical Republican and Champion of Democracy. Here are the talks I have scheduled so far: http://www.jeffreyboutwell.com/events

These also include a talk hosted by Jonathan Noyalas at the McCormick Institute on March 19. Many thanks, Jeffrey

Good article.

Thanks

Good article, but you should have included the role of Thaddeus Stevens in preventing the ex-Confederates from taking over Congress on December 4, 1865.

Excellent presentation of important issues.

Regarding your mention of the 1866 Civil Rights Act, the Civil War and Reconstruction Era certainly had (and continues to have) a major impact on the law right up to the modern era. For example, in the 2008 Supreme Court case of District of Columbia v. Heller, the Court found – for the first time – that the Second Amendment granted an individual right to bear arms. In support, the Court relied upon the findings of the Congressional Joint Committee on Reconstruction (1866), which described how African Americans “were routinely disarmed by Southern States after the Civil War.” The report of the Joint Committee deemed this conduct a violation of blacks’ Second Amendment rights.

It is difficult to imagine that many Northerners “assumed that after the Confederate defeat, Southern whites would accommodate their Black fellow citizens,” seeing as the Black Codes were invented in the North. Prior to the Civil War, Northerners made it very clear that, in the overwhelming majority, they did not want escaped slaves or free blacks living in their states, and thus the Black Codes, AKA Jim Crow Mark 1, were passed in many states, forbidding blacks to hold citizenship, own land, hold government office, bear witness against a white person, marry a white person – in some, blacks were even forbidden to take residence. Before and after the war, Northerners were hardly willing to “accommodate” blacks, and the majority of post-war race riots took place in the North, not the South.

The Black Codes in the Reconstruction South were not intended to copy Northern restrictive legislation. The Southern Black Codes were generally designed to keep Blacks working in their communities, not drive them out, under similar conditions that they had worked under slavery.

In that aspect, yes; in many others they were the same. There was a different, yet equally racist view in the North. For example, German immigrants, particularly in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, etc. were simultaneously opposed to slavery – they thought it a great sin – yet vigorously racist, and also had a pragmatic economic view of blacks: They did not want escaped slaves or free blacks living in those states because they saw them as unfair labor competition, knowing they would work for lower wages. So, they wanted them to not be there. Study American history. Following the Civil War, why was there no mass migration of freed slaves from the evil South to the crusading North? It took more than 70 years for blacks to make that relatively simple, easy trek up to Detroit, Chicago and other cities of the mid-West, drawn by the offers of good jobs in the factories producing America’s World War II war machine. Why didn’t they go before? Because they knew how they would be treated.

Racism was endemic before and after the Civil War. Prior to the CW, the 1851 Indiana Constitution prohibited free blacks from entering the state. Illinois had a statute forbidding any black person from staying longer than 10 days. In New York, blacks could not vote or file civil lawsuits. In Massachusetts, public transportation was segregated. Frederick Douglas refused to move from his seat. The conductor then removed the seats around his seat and then tossed him and his seat off the train. What the Southerners did after the CW was profoundly wrong. But, the black codes then still extant in Northern states limited their options.

Tom

Indeed it was, Tom. Thank you for contributing this valuable information.

Very informative and helpful perspective. Thanks

Thanks.

This is so cool! I’m currently doing an essay competition on a similar topic, and this is insightful 🙂