Willis Cole, the Battle of Bentonville, and the Southern Claims Commission, Part 2

ECW welcomes guest author Derrick S. Brown.

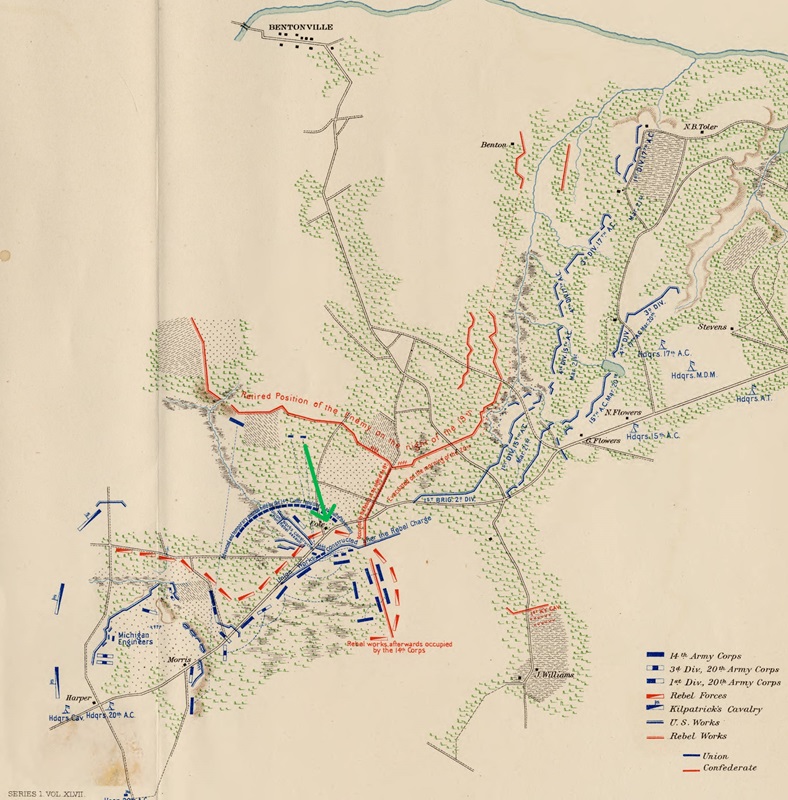

When part 1 ended, Willis Cole had begun the difficult process of proving his Union loyalties throughout the Civil War in order to receive reimbursement for his losses during and after the battle of Bentonville. To do so Cole testified to a commissioner appointed by the Bureau for Southern Claims that he disavowed his half-brother Bright for willingly enlisting in the Confederate army and “never supplied him with the first thing, clothing, supplies, or money.” According to Cole, Bentonville was a hotbed of Unionism during the war. He mentioned that Bentonville’s isolation allowed him to “run only with Union men … his few neighbors Joel Flowers and Green Flowers, and Reddick Morris. We mixed as little in public as possible and thus avoided threats.”[1]

Property damages were deemed ineligible for compensation by the commission, so Cole’s claims were restricted to livestock and commodities. Even with these limitations he compiled an exhaustive list of items from memory, which included horses, oxen, cattle, meal, lard, and animal fodder. One of the more substantial claims was for 10,000 pounds of bacon at $.25 per pound. All told Cole requested $5,950, which equates to over $115,000 today.[2]

Cole testified that he didn’t sit meekly as his possessions were requisitioned, as he claimed to have protested directly to Sherman and to Maj. Gen. Alfred H. Terry. However, the logistics of Cole’s appeals to these officers raises suspicions. Sherman never ventured to the Cole plantation, and a journey to his headquarters while the battle raged would have been fraught with danger, if not outright impossible. It can be said without equivocation that a conversation with Terry during the Bentonville fight was impossible because Terry and his Provisional Corps were miles away from the battlefield on March 19-21. However, Terry’s newly designated X Corps did pass through Bentonville on April 10. Perhaps it made Cole feel better to vent at the first general he encountered, but it is unclear why he thought Terry could help him recover stores that had already been consumed.[3]

Applicants’ testimony regarding their Unionist politics and property losses were not accepted at face value. Several witnesses were required to testify under oath regarding the legitimacy of each claim. Sub-commissioner for Wayne County John Robinson interviewed Cole’s wife and a stepson, Caroline “Sally” Cole and John Cogdell, respectively, as to how and why the items were taken. Cole’s neighbors, Joel Flowers and Bryant Williams, both avowed Unionists, testified that Cole was a thorough “Union man.”

The final witnesses deposed on Cole’s behalf likely carried the most weight. William A. Smith, Cole’s co-conspirator in the magistrate scheme (described in Part 1), was elected as a Republican congressman in 1872 and was able to testify to the commissioners in person in Washington. Like Cole, Smith enslaved more than twenty people before the Civil War, but there were few doubts about Smith’s loyalty to the United States. He had been amongst the loudest critics of Gov. Zebulon Vance and North Carolina’s participation in the Civil War. Smith’s vocal opposition to the Confederacy may have led to the targeted impressment of the enslaved people on Smith’s plantation by state authorities.[4]

Cole’s other star witness was Rufus Seaberry, a free man of color who lived in a tenant house on the plantation. Seaberry provided valuable anecdotes to his inquisitors about Cole engaging in verbal spats with Confederate sympathizers. As an African American, Seaberry’s testimony was more likely to be trusted by the Republican commissioners because, as Seaberry put it, “All our colored citizens were loyal [to the Union].” Seaberry testified that Cole once told him he wished Confederate President “Jefferson Davis was dead.” Cole also told Seaberry “that if he had a dog, he wouldn’t let it be called by so mean a name” as Jeff Davis. Before sending Seaberry’s remarks to Washington, Robinson took pains to annotate them to make sure the commissioners knew that the witness was Black.[5]

Cole submitted his claim in February 1872 and settled in for a long wait to hear the verdict. He likely became nervous later that year when fellow Bentonville resident Bryant Williams’ claim was summarily ruled against due to Williams’ service as a constable and later a magistrate. The difference was that Williams was an educated man who undertook his duties and thus was forced to swear a loyalty oath to the Confederacy, something Cole never did due to his illiteracy.[6]

After more than six years of waiting, a portion of Cole’s claim was paid on June 15, 1878. Of the $5,950 requested Cole received $2,875. The commissioners granted money for nearly every item on his list, but the values were decreased significantly; one example is that he received $1,000 for the 10,000 pounds of bacon instead of the $2,500 he requested. Although the approved amount may have been disappointing, it was the largest grant for the entire state during the 1877-1878 awards period.[7]

By this point the work of the Southern Claims Commission was winding down. The program had always been controversial, but its opponents were either too weak or too disorganized to stop it. Eventually an odd alliance of the most unrepentant Southern Democrats and radical Northern Republicans bandied together to oppose the SCC in the wake of the Compromise of 1877. Many Democrats thought claimants were traitors to their states, while Republicans feared that Democrats might expand the program to compensate planters for the loss of their slaves. In late 1878 the commission’s administrative functions, including the salaries of the commissioners, were defunded. The SCC was terminated by Congress in 1880 when some moderates, worried that the program was damaging reunion efforts, cast their ballots with the two extremist factions. [8]

Students of the battle of Bentonville, myself included, have often doubted the veracity of Cole’s claim. After all, he was one of the largest enslavers in the local community, which in and of itself raises doubts about his words of devotion to the Union. There is little doubt that Cole took great pains to avoid serving in the Confederate army – to include taking a job as a magistrate when he knew he couldn’t read or write – but that may have simply meant he didn’t want to be a soldier. Cole’s assertions that the Federal army confiscated or destroyed his missing items are also suspect, considering the Confederates held much of the plantation during the battle, and they were at least as hungry as Sherman’s men.[9]

Skepticism aside, I personally believe in the spirit of Cole’s claim, if not the letter. It is tempting to unambiguously assume that all planters were Confederate sympathizers, but many enslavers opposed secession and the Civil War. Some (correctly) feared that going to war against the North was likely to bring about the end of slavery, not preserve it. Furthermore, it is likely not a coincidence that Cole left Bentonville just as the community’s Confederate veterans were returning. Perhaps Bright wasn’t too keen on living near his Unionist brother after several months, stay in Elmira.[10]

Cole may have simply erred when he solely blamed the Federals for the ransacking and destruction of his plantation. These were Sherman’s men after all, and their reputation would have long preceded them. Finally, it is likely that Cole exaggerated quantities and costs during his deposition, but this was surely anticipated by the commissioners and is why his claim was adjusted downward.

If Cole desired to move back to Bentonville with the money he received, it must not have been enough. It certainly wasn’t a sufficient sum to rebuild his lost home or to reacquire the plantation. It was not until Cole’s 1899 death that he finally made it back to Bentonville for good, as his remains were interred just 250 yards east of his destroyed home.

Descendants of Willis, Bright, and of the people Willis enslaved continue to own portions of the plantation. However, the majority is now preserved by the State of North Carolina as part of Bentonville Battlefield State Historic Site, which is due to the generosity of the American Battlefield Trust and other organizations.

Derrick S. Brown is the operations manager at the Bentonville Battlefield State Historic Site.

Endnotes:

[1] Cole, Willis in US, Southern Claims Commission Approved Claims, 1871-1880, 14-17. Records Group 217, US National Archives

[2] Ibid, 10, 37.

[3] Mark L. Bradley, Last Stand in the Carolinas: The Battle of Bentonville (Campbell, CA: Savas Woodbury, 1996), 348-349.

[4] John Baxton Flowers III, Smith-Atkinson House, National Register of Historic Places nomination file, March 25, 1975.

[5] Cole, Willis in Southern Claims Commission Approved Claims, 1871-1880, 28-29.

[6] Williams, Bryant in US, Southern Claims – Barred and Disallowed, 1871, 12-16. M1407, US National Archives.

[7] Cole, Willis in Southern Claims Commission Approved Claims, 1871-1880, 3; Report of the Claims Commission, Weekly Raleigh Register, January 31, 1878.

[8] Susanna Michele Lee, “The Southern Claims Commission in Virginia.” Retrieved from https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/southern-claims-commission-in-virginia-the/

[9] When Wade Hampton occupied the plantation on March 18 and 19, he rode with a brigade from Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry corps. These men had a reputation for plundering in the Carolinas that rivaled Sherman’s hated bummers.

[10] Fellow Unionist Reddick Morris also left the Bentonville community in the war’s aftermath.

This was the last engagement in which my great grandfather participated.

The two flat stones inside the family cemetery were placed by my parents, Owen & Alma Jo Wilson. My dad’s mother was Effie Cole, daughter of Willis Cole’s son Julius Cole. The stones are for Julius Cole and his wife. My mother says that behind that cemetery is another burial ground but that trash has been piled on the site.