The Overlooked First Battle of the Retreat from Petersburg

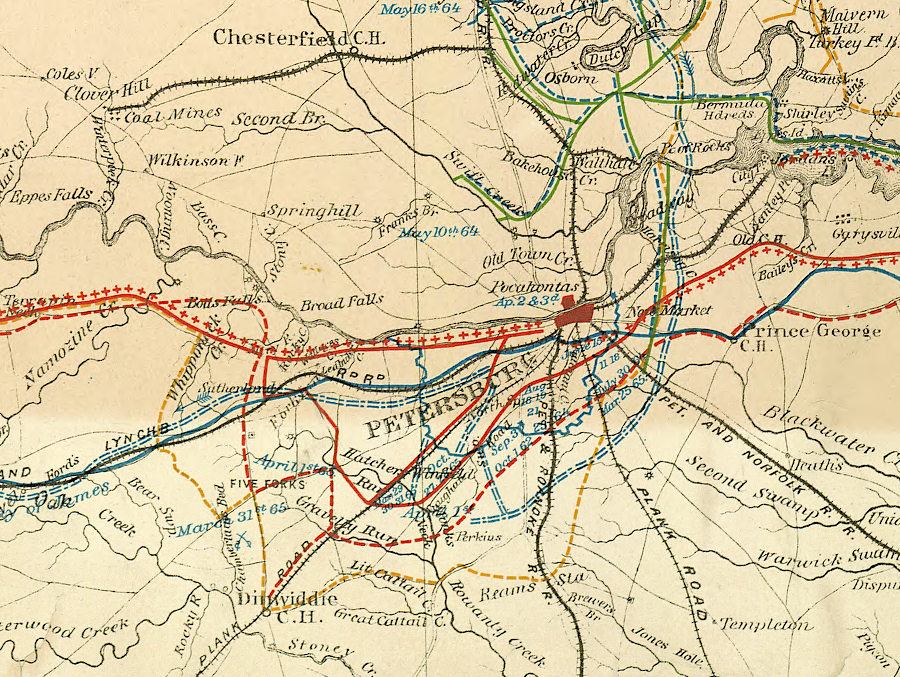

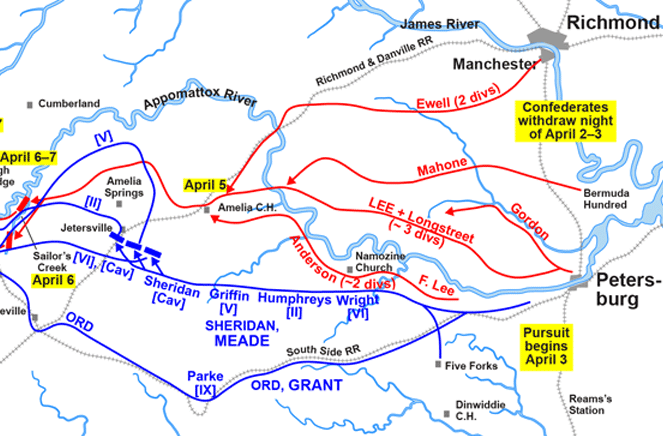

The Army of the Potomac and the XXIV Corps splintered Robert E. Lee’s defenses around Petersburg on April 2, 1865. In a series of thrusts, the Federal infantry cleared all resistance outside the city’s interior lines, severed the Southside Railroad, and made the Confederate position untenable. By the afternoon, Lee circulated orders to reconstitute his scattered command forty miles to the west at Amelia Court House.

Far on the outskirts and late in the day, a minor engagement occurred between a column of harried rebels and hounding Federal cavalry. This contest at the secluded intersection of Scott’s Cross Roads is seldom mentioned in even the most thorough studies.

At the time this article is written, Google searches for Scott’s Cross Roads return little information about the battle. Apart from unit pages detailing that a given command fought there, a 2019 article by Chris Calkins names it in a list of rearguard actions before Sailor’s Creek on April 6th.[1] An entry in the online Civil War Encyclopedia paraphrases the reports in the Official Records which form the totality of information on the skirmish.[2] Published materials either gloss over or fail to mention it altogether. It is time that Scott’s Cross Roads receives an article of its own, albeit with limited sources on the fight.

As the battle of Five Forks raged on April 1, Maj. Gen. Bushrod Johnson received orders from Lieut. Gen. Richard Anderson to relocate from the right flank of the Confederate lines to a crossing of the Southside Railroad north of their position. Johnson arrived at 2 a.m. and was soon joined by fractured elements of Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s and Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee’s commands. Intending to defend the railroad, at 11 a.m. they learned that Federals broke through the lines around Petersburg. Hearing a false rumor that Union cavalry had already reached the railroad to the east, they vacated their position at noon.[3] They moved west along Namozine Road in hopes of crossing the Appomattox at Exeter Mills and placing it between them and the Federal pursuit they knew would follow.[4]

Federal cavalry under Thomas Devin set out on the morning of April 2 and found themselves at the crossing at noon. By then, a cavalry division under Maj. Gen. Rooney Lee screened the Confederate withdrawal. Devin sent out skirmishers and formed lines of battle, but only a handful of artillery rounds convinced the Confederate cavalry to fall back.[5] The Unionists then took to tearing up a half mile of track before continuing their chase.[6]

This led them to conflict with their counterparts again, with the leading Union brigade under Col. Charles Fitzhugh repeatedly dismounting, firing, and hopping back onto their horses whenever they came upon the rebels.[7] Around 5 p.m., Fitz Lee asked Johnson to amass his infantry to oppose the blue-clad horsemen. Johnson’s command entrenched and further barricaded their position with fence rails, choosing Scott’s Cross Roads as the site for their defense. Here, only one road ran into Namozine Road from the southwest, one and a half miles away from Namozine Creek.[8]

Charles Fitzhugh’s cavalry brigade arrived at 5 p.m., and their first charge faltered under a barrage of steady small arms fire. Colonel Peter Stagg’s brigade dismounted to support their comrades, and Capt. Marcus Miller’s battery poured in accurate and steady fire, screened by the mounted Reserve Brigade. The artillery halted some halfhearted Confederate charges. The Federals made a second push at 6:30 p.m., successful in forcing the rebels into their breastworks but unable to unseat them.[9] The final charge took place around 8 p.m., after which darkness brought an end to the skirmishing.[10]

Both sides maintained their lines as they bivouacked.[11] The Federals held forward positions with the Reserve Brigade and one regiment of the First, while the remainder camped a half-mile to the rear. The Confederates made some attempts to feel the Union lines after sunset, but to no effect. Captain J.H. Bell rode out and opened communications with Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan at Sutherland’s Station and Maj. Gen. Samuel Crawford’s V Corps division scarcely one mile away.[12] The intelligence shared regarding this sizable, yet isolated Confederate force allowed these other units to aid the pursuit the next day and place near-constant pressure on the retreating rebels.

While Johnson’s men made a stand, Pickett’s command continued west. They discovered that spring rains rendered the Exeter Mills crossing unfordable. Some crossed on a small boat, but Pickett judged it too slow, and the majority continued along the road.[13] At 11 p.m., the rebels around Scott’s Cross Roads broke camp and commenced crossing Namozine Creek. By 2 a.m., the entire force, including the cavalry, had crossed, earning a brief respite from the ravenous chase.[14]

On the route to Amelia Court House, the Confederates saw action twice more at Namozine Church on the 3rd and Tabernacle Church on the 4th. It was not until the next day that they arrived at the rendezvous, but by that time Lee lost his one-day lead on the bulk of the Army of the Potomac.[15] Although this engagement was relatively small in scale, with neither side reporting casualty numbers, maintaining contact with the first group of retreating Confederates was invaluable. In the coming days, more Union troops closed in, culminating in the final battle and surrender at Appomattox Court House.

[1] Chris Calkins, “Hurtling Toward the End.” HistoryNet, Dec 2, 2019, https://www.historynet.com/hurtling-toward-the-end/.

[2] “Campaigns and Battles – S.” Civil War Encyclopedia, https://www.civilwarencyclopedia.org/campaigns-and-battles-s.

[3] OR, Series I, Volume 46, Part 1, pp. 1286-1291.

[4]Chris Calkins, The Appomattox Campaign, March 29-April 9, 1865 (Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, 1997): 54-55.

[5]OR, Series I, Volume 46, Part 1, pp. 1122-1127.

[6]OR, Series I, Volume 46, Par 1, pp. 1127-1129.

[7] OR, Series I, Volume 46, Part 1, pp. 1122-1127.

[8] OR, Series I, Volume 46, Part 1, pp. 1286-1291.

[9] OR, Series I, Volume 46, Part 1, pp. 1122-1127.

[10] OR, Series I, Volume 46, Part 1, pp. 1286-1291.

[11] OR, Series I, Volume 46, Par 1, pp. 1127-1129.

[12] OR, Series I, Volume 46, Part 1, pp. 1122-1127.

[13] Calkins 54-55.

[14] OR, Series I, Volume 46, Part 1, pp. 1286-1291.

[15] Ibid.

This article gave relevance to this battle in Petersburg and the impact it had in the Civil War.

Helpful new information on the early days of the Retreat. Thanks