A President’s Lost Election: James A. Garfield and the 7th Ohio Volunteer Infantry

ECW welcomes guest author Danny Brennan

On May 5, 1861, a portly figure crowded around his Ohio Senate desk to write a letter. For almost a month, James Garfield had tried to secure an officer’s commission to help quell the ongoing rebellion. The hopes of that twenty-nine-year-old politician seemed to die away that spring day. Describing the election for officers in the 7th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, Garfield wrote to his wife, “I do not know how it will turn,” while solemnly predicting that “I may not be elected.”[1] Just over nineteen years after he sent this message, Garfield participated in another election, this time for the nation’s highest office. His defeat for the colonelcy of the 7th Ohio may seem insignificant compared to his victory as president of the United States, but to the young man, any hindrance to participating in the nation’s greatest struggle was a devastating setback.

Garfield’s life had been a series of uphill battles. His father died before he reached the age of two, forcing him to work various jobs before he settled in as a teacher and school administrator. With a steady career, he married Lucretia Rudolph, or “Crete,” in 1858. Taken by the anti-slavery fervor growing around him, he consumed political writings before he offered the public some of his own. He turned his thoughts into action in 1859 by winning an Ohio senate seat with 58 percent of the vote.[2] As the nation divided itself and inched toward war, Garfield welcomed a sectional conflict out of the belief that it would cleanse his country of disloyalty and human bondage. “The war will soon assume the shape of Slavery and Freedom,” he predicted, stressing how “I believe the final outcome will redound to the good of humanity.”[3]

The senator was eager to play a role in the growing conflict and quickly used his legislative duties to support the war effort. But he also realized that his true desire was not to remain a mere observer in this fight. He declared that “the more I reflect on the whole subject, the more I feel that I cannot stand aloof from this conflict.”[4] Ohio Governor William Dennison trusted his young colleague, but the executive did not believe the legislator had enough military qualifications to warrant a direct commission. Garfield’s best chance for an officer job came by offering his services to one of the regiments being raised in the area, whose members by that time in the war selected their leaders by a vote. His first step into the realm of military leadership began by participating in a familiar electoral process.

Garfield did not have to look far to find a command that suited his interests. On April 25, he settled in Cleveland to help organize northern Ohio regiments. One unit was the 7th Ohio Infantry, which hailed from the same region as Garfield. The northeastern third of Ohio was known as the “Western Reserve” because it was once the westernmost holding of Connecticut. Even after it joined the Buckeye State in 1803, it still retained a New England sentiment for anti-slavery. The 7th’s ranks were filled with men from this area and represented “the flower of the Reserve,” according to one observer.[5] Garfield took a liking to his fellow northeast Ohioans, and the feeling seemed mutual. After spending some time with them, he noted on April 28 how “it now appears probable that I shall be elected Colonel of the 7th Regiment.”[6]

Whatever advantage Garfield may have had disappeared as he departed from the regiment’s camp. Tasked by Governor Dennison with securing weapons in Illinois, he left some friends in the Reserve in charge of securing his position.[7] William Bowler, a former student of Garfield’s in the 7th, and John Clapp, the husband of Garfield’s cousin, filtered through the ranks to convince soldiers of the merits of the absent politician. Other candidates had the advantage of remaining with the regiment, where they personally appealed to voters. Garfield added that his opponents secured support “by bargains and brandy.” All these methods led a Cleveland newspaper to note on April 30 that “there is considerable ‘electioneering’ in Camp today.”[8] The fruits of that maneuvering appeared two days later when Erastus Tyler secured a majority of votes in an informal ballot.[9]

Aware of this preliminary loss, Garfield expressed disappointment by accusing the contest’s presumptive winner of bad practice. Tyler, a fur trader from Ravenna, had served as a militia general who recruited and trained the men in the 7th’s Company G. It wasn’t Tyler’s experience that Garfield questioned, however, it was his integrity. Garfield said that the businessman “told me that he would aid me in the election” just before he left for Illinois. Then, in a “very unscrupulous” act, he “turned in and offered himself as a candidate.” Angry at this betrayal, Garfield declared that he would contest the election and continue his campaign “if for no other reason than to defeat Tyler.”[10]

The controversy over integrity led to a formal election on May 7. Lieutenant Oscar Sterl remarked that the “beautiful” day in Cincinnati’s Camp Dennison witnessed lively electioneering. “They now speak of a compromise between them,” Sterl stipulated, “but I have no confidence of its being consummated.”

It would be a winner-take-all contest. The balloting took most of the afternoon after the 3 p.m. start. But once all was tallied, the results were clear: Tyler won a commanding victory with 580 votes to Garfield’s 243.[11] One Clevelander of Company A recalled how the friends of the contest’s winners “gave vent to their satisfaction by toting them around the quarters on their shoulders.”[12] Those who pushed for Tyler’s rise literally elevated their candidate in celebration. Those who supported Garfield accepted the results, but continually blamed the defeat on the victor’s treachery as well as the loser’s inopportune absence.

The defeated Garfield was disappointed in his first electoral loss, but not broken. Dennison awarded his consistent political service in August 1861 by naming him commander of the 42nd Ohio Infantry by direct appointment, thereby saving him the hassle of another election. Colonel Garfield led this and four other regiments in a series of successful eastern Kentucky actions in early 1862, earning himself a general’s star. He led a brigade at Shiloh, but lost his command after a period of sickness. His final field assignment was as the chief of staff to William Rosecrans. After Chickamauga, then Maj. Gen. Garfield left the army to assume a congressional seat he won with considerably less effort than he displayed in the regimental election. He served as a representative until he resigned in 1881 to assume the presidency.

Despite his success, Garfield never forgot about his would-be command. While training the 42nd, he said that the surprise defeat of the 7th at the August 1861 battle of Cross Lanes “casts a gloom over everybody.” He noted how “Tyler is greatly blamed for being taken by surprise,” but in a surprising instance of reconciliation, continued by saying “perhaps however he was not in [sic] fault.”[13] He reversed the change of heart upon meeting with Maj. John Casement of the 7th, who described Tyler as “a coward and one of the meanest and most unmanly men he ever knew.” Garfield admitted to Crete that this testimony confirmed his earlier suspicions about his former opponent being “unfit for command.”[14] Garfield’s criticism aside, Tyler demonstrated his competence by commanding brigades in numerous battles and ended the war as a brevet major general commanding Baltimore. He settled in the Maryland city and served as its postmaster until President Garfield replaced him in 1881. After his brief stint in public service, Tyler succeeded in numerous business ventures until his 1891 death.[15]

Just as Garfield and Tyler overcame early setbacks, so, too, did the 7th Ohio. After their defeat at Cross Lanes, the 7th participated in battles in both the eastern and western theaters including, but not limited to, Cedar Mountain, Antietam, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and Ringgold Gap. Admirers dubbed them the “Roosters” because of their aggressive spirit. Even with an increasing number of northern Ohio units, they consistently functioned as the Western Reserve’s “pet regiment” until their term of service ended in 1864.

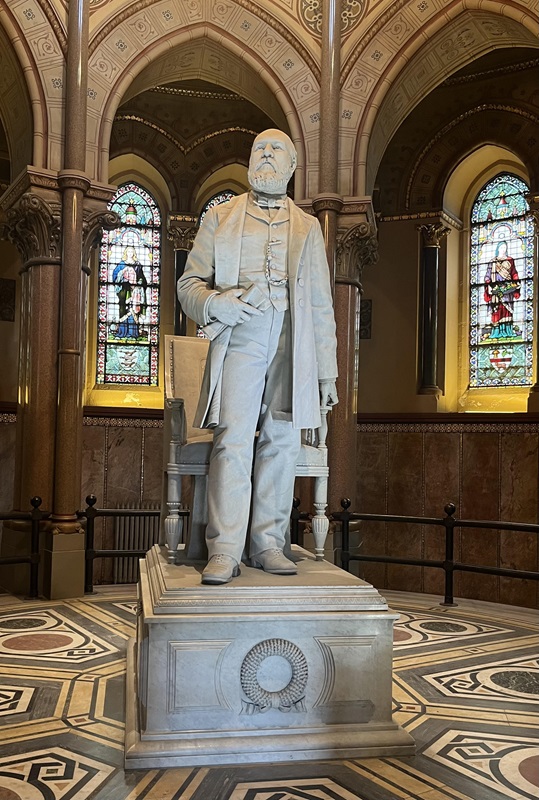

It can never be known if Garfield reflected on his first electoral loss after his presidential victory in 1880. In retrospect, the backstabbing and politicking in the spring of 1861 proved a minor setback to his remarkable story of self-making. He secured the military commission he coveted, serving in a war he predicted would bring about the “good of humanity.” As congressman and president, he desired to further bring out the good of his country. Unfortunately, his vision was cut short when infections that set in around an assassin’s bullet took his life on September 19, 1881, just 200 days after he entered office. Soon after, a mournful nation buried its leader in Cleveland’s Lake View Cemetery. Garfield became the cemetery’s most famous burial, but he was not the first. That distinction went eleven years earlier to Louis DeForest, a veteran of the 7th Ohio Infantry who doubtless voted in the 1861 officer election.

Danny Brennan is a PhD student at West Virginia University who works as a seasonal ranger at Gettysburg National Military Park. He is interested in exploring the Union Army in war and memory, focusing particularly on chaplains, Ohioans, and Twelfth Army Corps soldiers.

Endnotes:

[1] Garfield to Lucretia Garfield, May 5, 1861, Frederick Williams, ed., The Wild Life of the Army: Civil War Letters of James A. Garfield (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 1965), 14.

[2] Williams, xiii.

[3] Garfield to Rhodes, April 14, 1861, Williams, 5.

[4] Garfield to Lucretia Garfield, April 28, 1861, Williams, 10.

[5] “Professor Peck’s Address,” Cleveland Leader, December 9, 1863.

[6] Garfield to Lucretia Garfield, April 28, 1861, Williams, 10.

[7] Daniel Vermilya, James Garfield and the Civil War: For Ohio and the Union (Charleston: The History Press, 2015), 41-42.

[8] Garfield to Lucretia Garfield, April 28, 1861, Williams, 13.

[9] “The Seventh Regiment,” Plain Dealer, May 3, 1861.

[10] Garfield to Lucretia Garfield, April 28, 1861, Williams, 13-14.

[11] O.W. Sterl, “Another Letter,” Plain Dealer, May 9, 1861.

[12] “Our Army Correspondence,” Plain Dealer, May 10, 1861.

[13] Garfield to Lucretia Garfield, August 31, 1861, Williams, 34.

[14] Garfield to Lucretia Garfield, October 27, 1861, Williams, 43.

[15] Lawrence Wilson, Itinerary of the Seventh Ohio Volunteer Infantry 1861-1864 (New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1907), 365.

Congrats on your ECW debut, Danny! An excellent piece, and I’m looking forward to many more.

Thank you, Evan!

Garfield’s best boyhood job was muleteer on the Ohio * Erie Canal. There is an organized walk every year from his boyhood home in Orange, OH, to his tomb in Lakeview Cemetery in Cleveland on his birthday…the two spots are about 12 miles apart.

James Garfield’s connections to Northeast Ohio were certainly very strong-from his boyhood home, to the Ohio and Erie Canal, to his beloved “Lawnfield” home in Mentor (now the James A. Garfield National Historic Site), to his final resting place in Lake View Cemetery. Very few national figures can claim so many locations in such a contained space! I think that his loss in the 7th’s officer election particularly stung because the men he would have commanded were from this same area.

Mr. Brennan, Thank you for your article. As a serious student of James A. Garfield’s life and careers, both military and civilian, this will go into my “James A. Garfield” file. I recommend “The Diary of James A. Garfield.” Volume 1 includes the War years.

Thank you very much! It is great to hear from another student of Garfield’s life-too often the 20th president goes overlooked. And, yes, the “Diary of James A. Garfield” is a must-read!

The Garfield Monument is clearly the most visible site at Lakeview Cemetery, located on high ground about 120 blocks east of Public Square in Cleveland. I could see it from my 30 th floor office in downtown Cleveland. Lakeview Cemetery houses many other historical figures like John D Rockefeller and Jeptha Wade (his burial site includes a chapel with beautiful Tiffany glass). There was a Civil War training camp in Cleveland, overlooking the Cuyahoga River in an area known as Tremont. Historical markers and a replica artillery piece mark the spot- a good bet the 7th OVI trained there.

Glad to hear from a fellow-Clevelander! I have very fond memories of visiting Lake View with my family and I always try to visit there when I am in town. And as you mention, they did a good job interpreting the old Camp Cleveland site in Tremont (I went to school not far from there). The 7th was such an early regiment that they actually trained at Camp Taylor on the old county fairgrounds (now East 30th and Woodland Avenue). But you are correct in assuming that the regiment has a connection to Tremont’s Camp Cleveland-it was there that they mustered out in 1864!

It’s amazing how little many of us know about President Garfield. There are others that served in the Civil War, also. In all, how many presidents served in the Civil War? Numbers and names, anyone? Thank you,

Great question, Judith! It all depends on how you count them. Five future presidents served during the war in combat roles: Ulysses Grant, Rutherford Hayes, James Garfield, Benjamin Harrison, and William McKinley. All the men were natives of Ohio and all rose to an officer’s rank by the end of the war (Grant, naturally, had the highest rank as commanding general of the U.S. Army and McKinley had the lowest, ending his service as a brevet major). Hayes and McKinley also served with one another in the same regiment-the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Chester Arthur did not see any fighting, but he did serve as New York’s Quartermaster and Inspector General, technically earning him a Brigadier General’s rank. And then two presidents served as commander-in-chief during the war: Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson. So if you add up the men who served in combat (5), in administrative positions (1), and as the commander-in-chief (2), you get eight total presidents who contributed militarily to the Civil War. Hope this helps!

No doubt you know this, but Andrew Johnson was made a brigadier general by Congress upon being appointed military governor of Tennessee by Lincoln in 1862. He definitely had an administrative position, but he might be considered a combat leader as well as he fought Confederate partisans throughout Tennessee and supported the Union armies operating in or out of Tennessee.