On the road to Atlanta: Ruff’s Mill, July 4, 1864

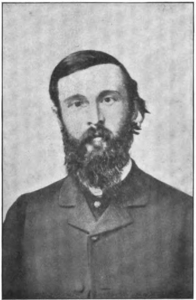

On the afternoon of July 4th, Col. Edward F. Noyes, commanding the 39th Ohio, recalled how Sherman “looked all along the line and said: ‘Here’s the place to strike them, and we are going to do it right away.’” At that Noyes stepped up, insisting that his men “can and will take the . . . works. All we need is the order.” Sherman, delighted by Noyes’s confidence, decided the matter: the charge would be made at “six o’clock.”[1]

Noyes was a veteran, having held both the majority and the lieutenant-colonelcy in the 39th before his promotion to full colonel in late 1862. An ardent patriot, he had zealously campaigned within the 39th for veteran reenlistment over the winter of 1863, which induced the men to reenlist in record numbers. As the current campaign opened, the 39th fielded 638 men, while the 27th counted 536; and though now much reduced, the two commands probably still numbered close to 1,000 troops. Earlier, Noyes believed that Fuller chose the twin Buckeye regiments to make the assault because “we could do it successfully, if anybody could;” when told to stand down, “it was a terrible let-down. I felt as if it were a sort of slur.” Now both regiments formed up behind the spencer-armed 64th Illinois, which Fuller had left on the skirmish line, while behind them the much smaller 18th Missouri formed in support. As further support, since Fuller only had four regiments, Veatch loaned him the 63rd Ohio from Brig. Gen. John Sprague’s Second Brigade. Then, wrote Noyes, “at six o’clock and 40 minutes—I remember perfectly well the hour—the bugle sounded the charge.”[2]

Noyes was a veteran, having held both the majority and the lieutenant-colonelcy in the 39th before his promotion to full colonel in late 1862. An ardent patriot, he had zealously campaigned within the 39th for veteran reenlistment over the winter of 1863, which induced the men to reenlist in record numbers. As the current campaign opened, the 39th fielded 638 men, while the 27th counted 536; and though now much reduced, the two commands probably still numbered close to 1,000 troops. Earlier, Noyes believed that Fuller chose the twin Buckeye regiments to make the assault because “we could do it successfully, if anybody could;” when told to stand down, “it was a terrible let-down. I felt as if it were a sort of slur.” Now both regiments formed up behind the spencer-armed 64th Illinois, which Fuller had left on the skirmish line, while behind them the much smaller 18th Missouri formed in support. As further support, since Fuller only had four regiments, Veatch loaned him the 63rd Ohio from Brig. Gen. John Sprague’s Second Brigade. Then, wrote Noyes, “at six o’clock and 40 minutes—I remember perfectly well the hour—the bugle sounded the charge.”[2]

What next occurred was a shock to both sides. “Men never went faster or cheered louder,” wrote Lieutenant Smith. Ordered to reserve their fire until close, “it seemed but a few minutes before the charging column was out of the woods, across the open fields, and were swarming over the enemy’s earthworks.” Smith recorded that the Buckeyes captured “a regiment of North Carolina and Georgia troops, and with a great shout of triumph, raised the old flag over their conquest. The rest of the enemy fled, several were bayonetted in the fight at the works.” Sergeant Wright described how “with a demon-like yell we spanned the clearing and gained the ditch in a twinkling the enemy running with all speed. We only reached the works in time to fire one volley at the receding line which was [soon] submerged in the dense underbrush.”[4]

Federal losses, while not light, were not crippling. The 39th reported five killed and 31 wounded. The 27th’s regimental loss was unreported, but the brigade report showed 14 killed and 89 wounded. In his postwar history, Smith put the 27th’s and 39th’s combined loss at “over 140 men” total, though that might include casualties from the morning skirmishing. In his journal, Surgeon Pierre Starr wrote that “the thirty-ninth lost thirty-six privates and three officers; the twenty-seventh lost forty-one.”[6]

Among those hurt was Colonel Noyes. “I did not get very far,” Noyes remembered, “not more than a third of the way” across the field before the Rebels “put a minie ball into my ankle joint. I sat down on the stump of a tree and the boys went on, making a whole through the enemy’s line—big enough to put their whole army in full retreat before daylight the next morning.” Observing Lt. Silas Lossee “laying the flat of his sword across the back of a fellow as hard as he could,” Noyes demanded what the lieutenant was doing. “Teaching this fellow how to make a charge,” Lossie snarled, continuing to flail at the straggler. “After you get through, come back here,” replied Noyes. Eventually Lossee and some others helped Noyes to the rear, where Noyes remembered that they “met a lot of officers, Dodge, Fuller, and Sherman among them. . . . ‘Are you badly hurt?’ they asked me. ‘Well,’ I said . . . ‘I was ordered to take those works and I have taken them. And I shouldn’t wonder if they had taken one of mine, but it’s the 4th of July and I don’t give a copper.’” With the ankle shattered, Noyes lost his leg below the knee. He would eventually return to garrison duty, but his days in the field had ended.[7]

————

[1]Smith, Fuller’s Ohio Brigade, 158, 331-32; Larry M. Strayer and Richard M. Baumgartner, eds., Echoes of Battle The Atlanta Campaign An Illustrated Collection of Union and Confederate Narratives Huntington, WV: 1991), 139.

[2] Smith, Fuller’s Ohio Brigade, 332; XVI Corps Returns, March 31, 1864, RG 94, NARA; Strayer and Baumgartner, Echoes of Battle, 139-40. There are no XVI Corps returns later than March, 1864. The subsequent returns are misfiled or lost.

[3]Brad Quinlin, “For my Grandchildren” The Civil War Journey of Pierre Starr (Alpharetta, GA: 2018) 68; “From Sherman’s Army,” Cincinnati Daily Commercial, July 11, 1864; “July 4, 1864,” Francis Marion Wright Diary, KMNBP.

[4]Smith, Fuller’s Ohio Brigade, 158; “July 4, 1864,” Francis Marion Wright Diary, KMNBP.

[5]Jeffrey C. Weaver, 63rd Virginia Infantry (Lynchburg, VA: 1991), 60; Michael C. Hardy, The Fifty-Eighth North Carolina Troops Tar Heels in the Army of Tennessee (Jefferson, NC: 2003), 125; OR 38, pt. 5, 47.

[6]OR 38, pt. 3, 490, 501; Smith, Fuller’s Ohio Brigade, 158.

[7]Stayer and Baumgartner, Echoes of Battle, 140.

Thanks for these stories of brave men.

Brave men for sure. Clearly there was enough bullets in the air to cause fear in at least one straggler. Any idea of the strength of arms that they faced? My back of the napkin guestimate: By this time in the war the Rebs knew how to shoot accurately. If there were 150 casualties, and each Reb got four volleys off, (with undefined amount of artillery support,) at a 5% hit rate, back of the napkin saying there was approximately 3,000 gray pills whizzing thru the air, with each Johnny getting an estimated by me 4 shots off it sounds like I’d guess 1,000 charging Yanks faced about 750 front line soldiers. The higher the hit rate, the fewer guys the Union charge faced.