Bagdad Raid: When U.S. Troops Fought the French in Mexico

The French Empire occupying Mexico faced significant opposition from guerillas who fled into Texas to evade capture. The Marquis de Montholon wrote to Secretary of State William Seward in 1865, accusing the U.S. of violating its neutrality and demanding a crackdown along the border.[1] Instead of addressing the claims, Seward responded, “The French army which is now in Mexico is invading a domestic republican government there which was established by her people, and with whom the United States sympathize most profoundly, for the avowed purpose of suppressing it and establishing upon its ruins a foreign monarchial government, whose presence there, so long as it should endure, could not but be regarded by the people of the United States, as injurious and menacing to their own chosen and endeared republican institutions.”[2] While claiming neutrality, America would oppose the French, even to the point of launching an armed occupation.

Major General Lew Wallace always had a fascination with Mexico. Best known as the author of Ben-Hur, he was an avid consumer of Mexican literature and became familiar with the geography and people from service as a First Lieutenant in the Mexican-American War.[3]

This experience readied him for impressive performances fighting for the North. As the Civil War began to wind down, the Union had two significant adversaries remaining in the west. Leaders such as Ulysses S. Grant feared having to combat the Confederates west of the Mississippi as well as the French in Mexico. Wallace proposed convincing the rebels to fight alongside the Union against the foreign monarchy. Grant dispatched Wallace to the border to investigate this possibility, but did not give him authority to enter into any agreements.[4]

This plan did not come to fruition, yet Wallace maintained his sympathy for the Mexican people. When the Civil War ended, he received a unique offer to aid the elected government of Benito Juarez against the French Imperials.[5] Wallace accepted his clandestine appointment, attaining a Major General’s commission and an additional $100,000.[6] His primary objective was to hamper French efforts near the border

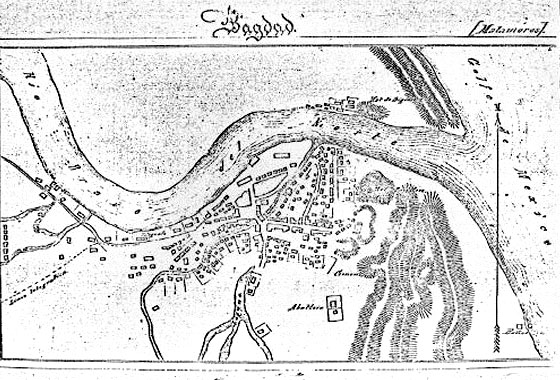

Bagdad was a tiny fishing village strategically located where the Rio Grande empties into the Gulf. The Union blockade and the fall of Vicksburg created serious supply problems for the Trans-Mississippi rebels. Trading across the border was a convenient workaround, and Bagdad grew into a city with a population of 2,000. Southern cotton flowed into Bagdad, loaded onto foreign vessels that exchanged the commodity for imported goods. It was not uncommon to see seventy ships from various nations in port there.[7] When the Civil War was over, Bagdad lay in French hands. Seizing the city could allow Juarez’s forces, the Juaristas, to control the Rio Grande.[8]

R. Clay Crawford, a former Confederate, received orders from Grant to take an active role against the Empire.[9] In late 1865, with secret Federal approval, he opened a recruiting station in Brownsville, Texas for an expedition to occupy Bagdad. Crawford sought in part to free seventeen men under his command held there, awaiting execution for fighting against the Empire. Although there is no record of a previous excursion, their imprisonment clearly suggests something of the sort.[10]

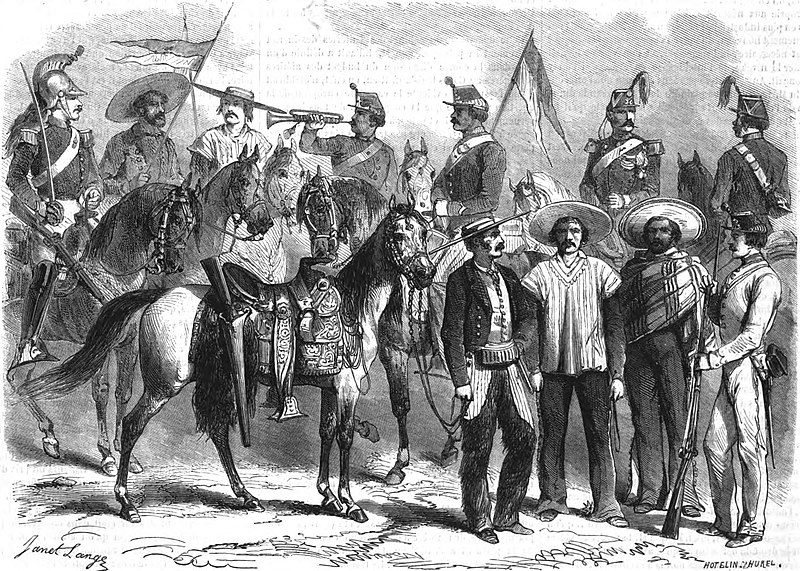

Recruits were offered fifty dollars a month and all expenses paid. Those who took up the offer included soldiers from the 118th USCI as well as deserters and civilians. This group of filibusters numbered 120 men, and set out from Clarksville, Texas.[11] Crawford convinced outlaw Mexican General Juan Cortina to make a demonstration at the nearby town of Matamoros to prevent reinforcements from coming to Bagdad. On January 4th, 1866, many of the adventurers crossed the river and overnighted at a hotel. Rising early the following day, they quickly captured the Imperials guarding the ferry around 4 am. This enabled their comrades, many of whom were USCI in-uniform, to cross the Rio Grande.[12]

The Imperials had intelligence that a body of guerillas, supplemented with African-American recruits, was patrolling in the vicinity. A small detail of French cavalry attempted to track them down, and just as they returned to Bagdad, the filibusters began galloping down the main road firing towards them. The Major in command sent a messenger to request that a ship in port signal for help, and delegated another group to fortify the customs house. He amassed his infantry in a wedge formation in the plaza ahead of the building. The plaza allowed entry on three sides, so this deployment allowed his men to engage in any direction. The raiders encircled their adversaries and charged. Two French volleys forestalled the advance for a few moments, but ultimately, Crawford’s band reached their lines and a hand-to-hand fight ensued. Despite the bedlam, the defenders conducted an orderly withdraw, inverting the tip of the wedge to create a crossfire, then slowly drawing the wings inward.[13]

The Imperials barred the door as soon as they were all in the customs house. With entryways only secured by furniture and loose boards, it was apparent that they would not hold long. As the Americans beat upon the door with axes and battering rams, a breakthrough seemed inevitable. Yet a French gunship, alerted by the signal from the other vessel, poured shells into the attackers and killed two African-American troops.[14] They fell back so quickly that when the garrison opened the customs house door to add musketry to the barrage, they could find none of their heretofore attackers.[15]

Though Crawford’s men did not bring artillery, they maneuvered a captured cannon to return fire on the gunboat. They killed two sailors and damaged the hull, forcing the crew to make for the safety of the Gulf. The garrison soon surrendered, and the looting of the town began. Casualties numbered four dead and eight wounded for the filibusters and eight dead and twenty-two wounded on the Imperial side. The party commandeered nearly fifty small boats to unload their plunder on the opposite bank.[16]

Although Cortina took part in the scheme, he did not share the plan with any other Juaristas. His comrade, Colonel Enrique Mejia, learned of the situation and occupied the town with 200 volunteers. Many of them were guerrillas who came out of hiding from across the border. Mejia’s arrival initially infuriated the Americans, who briefly imprisoned him before welcoming the Juaristas.[17]

At this time, many of the active-duty men returned to Texas. Chaos still reigned, and Mejia requested 200 American soldiers to restore peace. As the unit was close at hand, 200 men of the 118th USCI were dispatched, and eventually 100 more were needed to pacify the town.[18] Major General Godfrey Weitzel responded to concerns from American merchants about their property, and had no desire to escalate the incident.[19] He arrested Crawford, and the remaining raiders were paroled until trial and ordered back to the American side.[20]

Another African-American unit relieved the 118th soon after. On the 22nd, the U.S. troops withdrew, handing control over to the Juaristas.[21] Just three days later, over 500 Imperial soldiers advanced into Bagdad and compelled Juarez’s men to evacuate speedily.[22]

The Imperial forces took stock of storehouses and found that the occupiers had removed over 100 boxes of valuables and taken two light ships. Federal commanders in the region responded to the French inquiry with ambivalence. They explained that Juaristas seized many of the supplies, and the remainder, which the French knew was at Clarksville, was claimed as personal property. As such, the military had no jurisdiction, and it was suggested that they take up the matter in civil court![23] The official U.S. policy was that those who took part in the raid were mustered out of service and were thus not acting as soldiers.[24]

The Vice-Consuls of England, France, Spain, and Prussia forwarded a note of protest from merchants in Matamoros against American support for Juarez. All considered Maximilian I the rightful Emperor of Mexico and cautioned that continued support could cause the conflict to expand into the Texan frontier.[25] Yet the U.S. paid them no mind. Crawford soon escaped captivity, and the other filibusters never stood trial.[26] This lack of prosecution further demonstrates Federal leadership’s tacit approval of this incursion.

Trepidation from the assault dissuaded the French from campaigning in the north, opting instead to hold fortified positions against the Juaristas who continued gaining momentum.[27] American commanders accelerated the covert flow of war materiel to their allies, whose capture of Matamoros in June was a death knell for the Empire.[28] The last French troops left the country in March 1867, and by May, Benito Juarez stood victorious. Once again Mexicans exercised sovereignty over their own nation.[29] The Bagdad Raid affirmed American commitments to preventing European interference in the hemisphere, and to government by the people, for the people.

————

[1] OR, Series 1, Vol. 48, Part 2, 1241

[2] William H. Seward to the Marquis de Montholon, December 6, 1865, https://www.solon.org/misc/Mexico/US/seward_18651206.html.

[3] Robert Ryal Miller, “Lew Wallace and the French Intervention in Mexico,” Indiana Magazine of History 59, no. 1, (1963): 31, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27789044.

[4] Jeffrey William Hunt, The Last Battle of the Civil War (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2002), 27-28.

[5] Miller, 31.

[6] Indiana State Library, “Oliver P. Morton Papers”. Finding Aid, Indianapolis, 2007. https://www.in.gov/library/finding-aid/L113_Morton_Oliver_P_Papers.pdf.

[7] M.M. McAllen, “Life Lived Along the Lower Rio Grande During the Civil War,” in Civil War on the Rio Grande, 1846-1876, ed. Roseann Bacha-Garza, Chistopher L. Miller, Russell K. Skowronek (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2019): 59-65.

[8] William S. Kiser, Illusions of Empire: The Civil War and Reconstruction in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022): 140.

[9] William Lee Richter, “The Army in Texas During Reconstruction, 1865-1870” (Ph.D. dissertation, Louisiana State University, 1970): 70. https://scispace.com/pdf/the-army-in-texas-during-reconstruction-1865-1870-q07zhlfy33.pdf.

[10] Miller, 43.

[11] W. Stephen McBride, “From the Bluegrass to the Rio Grande: Kentucky’s U.S. Colored Troops on the Border, 1865-1867,” in Civil War on the Rio Grande, 1846-1876, ed. Roseann Bacha-Garza, Chistopher L. Miller, Russell K. Skowronek (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2019): 211.

[12] Jerry Thompson, Cortina: Defending the Mexican Name in Texas (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2007): 167-168

[13] Maximilian Alvensleben, With Maximilian in Mexico: From the Notebook of a Mexican Officer (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1867): 49-53

[14] Miller, 44.

[15] Alvensleben, 53-55.

[16] Thompson, 168.

[17] Miller, 44.

[18] McBride, 211.

[19] Miller, 44.

[20] Richter, 71.

[21] McBride, 211.

[22] Thompson, 169.

[23] H. E. Wright to Enrique Mejia, January 22, 1866, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1866p3/d58.

[24] Stephen A. Townsend, “The Rio Grande Expedition 1863-1865” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Texas, 2001): 252. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc2744/m1/256/.

[25] Dimas de Torres Velasquez, C.U.Frossard, Luis Schuhmacher, Chas. Bagnall, “Protest of the merchants and residents of the city of Matamoras against the acts of the government of the United States and its representatives.” January 23, 1866. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1866p3/d34.

[26] Richter, 71.

[27] Hubert Howe Bancroft, History of Mexico, Volume 6 (Charleston, SC: Nabu Press, 1866): 250. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/History_of_Mexico_(Bancroft)/Volume_6/Chapter_11.

[28] Richter, 71-74.

[29] Alan Taylor, American Civil Wars: A Continental History, 1850-1873 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2024): 368-369.

Very informative article. Good description of the raid In Bagdad.

Fascinating. As for Wallace (my spouse’s ancestor), was he still a serving U.S. officer when he took on his role and accepted payment?

What an interesting ancestor to have! He was not, although the offer by Mexican General Carvajal was made on April 26, 1865, prior to and contingent upon his resignation. The plan was put on hold as he had to serve on the commission investigating Lincoln’s assassination. As such, his resignation was not final until November 30th, at which time he went to the border. If you have access to Jstor, I highly recommend reading Robert Miller’s article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27789044.

Aaron, thank you. I’ll read the article. As a brief humorous aside on the family Wallace connection, many years ago I took my son (then perhaps age six or so), to a local New Jersey Civil War battle enactment. We visited the tent of the 14th NJ, known as “the Monocacy Regiment,” whose members proudly recounted their history of fighting at Monocacy under General Lew Wallace. I had my son tell the men his full name – John WALLACE Donovan. They went wild when I said yes, he is descended from THAT Wallace.

Fascinating! Sort of the plot to “Major Dundee” minus the Apache.

Outstanding research! Aside from Ben Hur and Wallace’s spotty Civil War record, I was unaware of his involvement in Mexico.

The notion that Crawford was a former Confederate is an oft-repeated error. He was a Union officer. Also, the seventeen men captured in Mexico and facing execution were not under Crawford’s command.

Regarding Crawford as a Union, not Confederate, officer, see pages 1193 and 1205 of this publication. https://www.milamcountyhistoricalcommission.org/1057.pdf

He was captured and held in a Confederate military prison, then paroled and sent North. See Chi. Daily Tribune. 17 October. 1862.

More records showing that Crawford was a Union officer. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/41621510