The Civil War’s Hidden Hospital: Lee-Fendall House’s Forgotten History

ECW welcomes guest author Madeline Feierstein.

In 2024, the Lee-Fendall House Museum & Garden, at the corner of Washington and Oronoco streets in Old Town Alexandria, celebrated its 50th year as a private museum. Since 1974, visitors have been guided through the period-themed rooms. They are regaled with tales of its aristocratic residents, high-profile guests, and modernization. Absent from the richly-detailed tour script was any specific account of the Grosvenor Branch Hospital. The two years that Lee-Fendall was converted into a Civil War hospital had been obscure and mysterious for 160 years – a mere footnote in the daily house tours offered by its docents.

Although it is widely known that the house was confiscated by the Union Army in April 1863, little physical evidence is left of the wartime years. The 1850 renovations persevered through the gruesome experiences of battles’ aftermath and infectious disease, remaining relatively pristine when postwar occupants returned the home back to its prewar glory.

The Lee-Fendall House was constructed in 1785 by Phillip Fendall, who bought the land from his cousin, Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee. It was consistently a private residence until 1972, except for the disruption caused by Civil War. The Lee family, along with the Downhams and Lewises, lived full lives within its walls.![]()

I joined the Lee-Fendall team in June 2022 as a volunteer docent. The trajectory of my time at this incredible site and my overall research objectives were turned on their heads when, that summer, staff was granted first-time access to its Civil War medical ledgers.

I was attracted to the museum’s wartime history even though, until recently, no one had any idea how many soldiers were admitted, for what diseases or wounds, or how many never left alive. Three individual registers held at the National Archives kept the secrets of this stately residence, but since the legers were not labeled by hospital name, it was only recently that the proper leger books were linked to the Grosvenor Branch Hospital. While the task to interpret these tattered pages was daunting, it was the right combination of time, place, and eager volunteers; a kismet feeling that reverberated throughout the museum. It felt, as if cosmically, the energy in the historic home had shifted: The Grosvenor Branch Hospital, once lost, was now found.

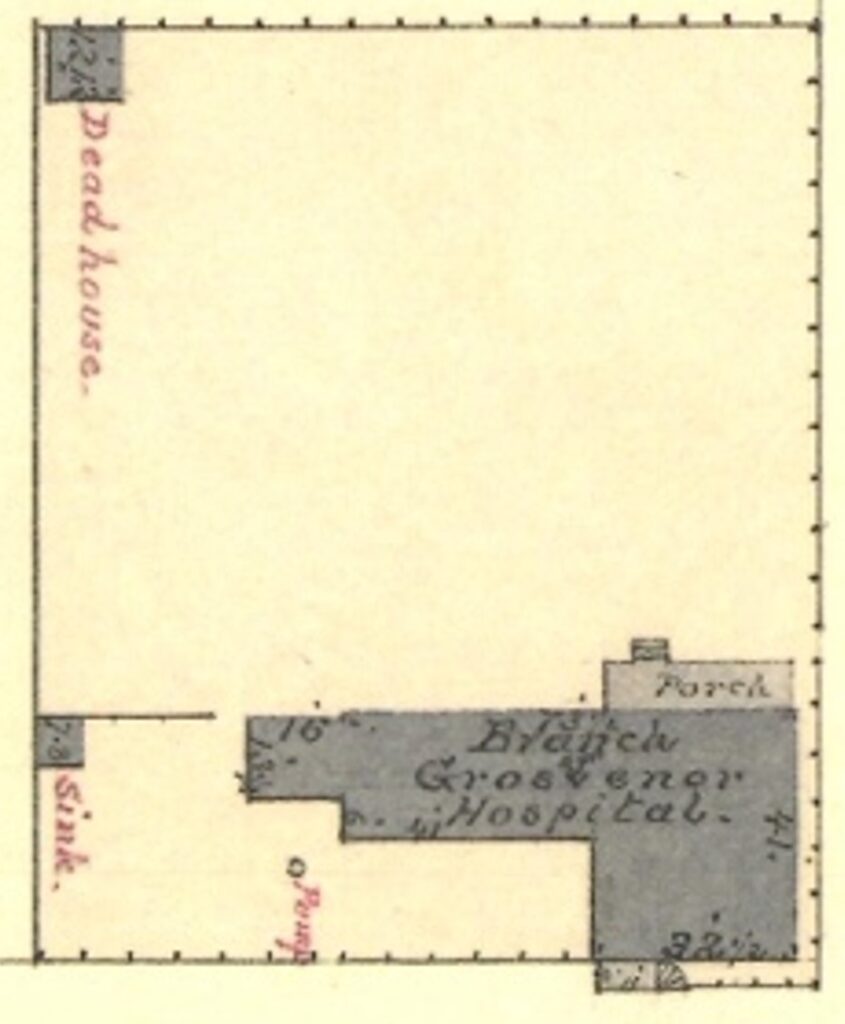

Before 2022, there were only two accepted facts regarding the hospital. Most significantly, Grosvenor Branch was the site where the first successful blood transfusion of the conflict occurred. Ample information is available regarding Head Surgeon Dr. Edwin Bentley’s operation on Pvt. George Cross. Secondly, the first floor was utilized as wards while the upper two floors were reserved for officers’ quarters. This explains why a new set of floorboards covered the original 1785 pine planks on the ground level beginning in 1870. However, it also inflated who we believed to have stayed at the museum. The idea of “officers’ quarters” sprouted into a hopeful belief that high-ranking officials – and maybe even higher-profile names in Civil War America – resided temporarily in our small house museum.

These ledgers told more tales than we ever could have imagined. Not only did we uncover facts and undeniable evidence of what had been hearsay, but additional information that was refreshing.

The Lee-Fendall House was built in the Maryland telescope style, which blessed the floor plan with large, spacious rooms. This allowed for a fluctuating capacity of 146-156 beds at any given point. One of my favorite questions to pose to visitors asks them to guess the capacity of our hospital, giving them time to peruse the first floor. Many hover at 50 or 90 spaces for soldiers to rest; even more are shocked to learn that the museum fit double that amount. Staff, too, are perplexed as to how our first floor accommodated such a bustle of patients, operating surgeons, stressed attendants, and support staff in these cramped conditions.

One tedious task to implement in this pet project was to transcribe all of the entries across the three bound volumes. Through documenting each and every story, we have been able to compile a comprehensive and fluid history of those lost years and dispel lingering myths regarding the hospital.

I needed to be a bit obsessed with the medical history of Grosvenor Branch in order to enter all patients into an Excel spreadsheet. With the help of Civil War historian and Lee-Fendall board member Roger Monthey, we tackled the books for several months.

Confusingly titled “Register 460,” “Register 461 ½,” and “Register 462,” these volumes were part of the larger collection “Field Records of Hospitals, 1821-1912.”[1] Once we compiled our individual data sets, a clear problem presented itself: The surgeons had listed every discharge, furlough, return to duty, and return from furlough as a new entry, skewing the total number of admissions. Over the next six months, the task now reaching close to a year, I eliminated duplicate entries and condensed all entries for each soldier into one simplified Excel row. By summer 2024, I had totaled the number of admissions to an even 1,700.

This also influenced the death toll, which was recently finalized in winter 2025. The number used to range from 105-150 deaths in the home, but it is now concretely stable at 100 cases of death.

There were abundant obstacles to confirming this tragic total. Some ledger entries were incomplete. At times, the surgeons did not mention the death of a patient, while others were mistakenly listed as deceased. It was through the painstaking research on databases like Fold3 and Ancestry that I was able to ascertain if the soldier died during his treatment at Grosvenor Branch through matching the admission or date of injury.

While Grosvenor Branch did not admit any generals during its operation, laying to rest that perpetuated notion, it notably treated 80 sergeants, 76 corporals, and 20 captains, as well as two commissary sergeants and two quartermaster sergeants. Additionally, thirteen musicians entered the hospital along with a sprinkling of wagoners and stewards. A sizable portion of the admissions were privates (~84 percent), further confounding the fact that they were all quarantined on the first floor.

In my handcrafted specialty house and walking tours related to Lee-Fendall’s Civil War history, and by extension the City of Alexandria, it was critical to tell these soldiers’ tales holistically. They were more than numbers in a spreadsheet and entries in an aged ledger. By expanding on the information provided in the ledger, such as admission from a requisitioned military prison or transfer to the federal insane asylum in Washington, I was able to paint experiences rather than pure data. Muster roll and service records told me a greater story: age upon enlistment, previous occupation, eye color, hair color, and height. These soldiers became men, once again, and often reminded us that many were mere boys.

Once I identified over 150 prisoners who were admitted for treatment, I ventured into the prison registers at the National Archives.[2] By spotlighting the individual prisons themselves, it became clearer why so many were transferred from the neighboring Washington Street Prison in particular: Superintendent Rufus D. Pettit’s reign of terror against suspected deserters sent dozens to Dr. Bentley’s care at Grosvenor Branch. Prisoners alone account for around 9 percent of the total admissions to the hospital, beginning in November 1864 and lasting through the hospital’s closure in April 1865.

Much is left to be uncovered and even more to be demystified. There is no record describing the state of Lee-Fendall once the surgeons packed their instruments and the nurses removed all semblance of hospital activity. One can imagine that, after two years of hosting over 1,700 injured and diseased soldiers, the conditions would be deplorable. Besides a good scrubbing and refurnishing, since all the original furniture was removed and never returned, the Lee family likely ordered a fresh coat of interior paint or wallpaper – plus a restoration of the garden which may have been plucked dry of medicinal herbs.

Researching the hospital benefitted more than the specialty house tour that I conduct monthly. Through deep-diving into specific experiences, it gave birth to new research interests and opportunities. With my additional work with the local tour company Gravestone Stories, we have also enumerated over fifty patient burials in the historic Alexandria National Cemetery, further connecting the narrative of Grosvenor Branch to the story of Alexandria. As an organization, we have continuously recognized the medical achievements, astonishments, and tragedies that occurred within our walls. We view these ledgers as living, breathing historical documents – ones that should be shared with the public and discovered by all.

Madeline Feierstein is an Alexandria, VA historian specializing in the American Civil War’s hospitals and prisons. A native of Washington, D.C., her work has been showcased across the Capital Region. Madeline leads efforts to document the sick, injured, and imprisoned soldiers that passed through Civil War Alexandria. Additionally, she interprets the burials in Alexandria’s historically rich cemeteries with Gravestone stories and supports the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Maryland. Madeline holds a Bachelor of Science in Criminology from George Mason University and a Master’s in American History from Southern New Hampshire University.

Endnotes:

[1] “Field Records of Hospitals, 1821-1912” in Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1762–1984, National Archives, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/655731.

[2] “[Washington Street Prison] Lists, Registers, and Reports, 1864–1865” in Records of U.S. Army Continental Commands, National Archives, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/1726573.

Also in Alexandria, VA, visit the Carlyle House where numerous colonial governors met with General Braddock in 1755 as part of the Braddock Expedition, etc. Afterwards, General Braddock went on a one-way trip through Fox’s Gap in Maryland (i.e., later Battle of South Mountain, 9-14-1862) in order to capture Fort Duquesne. Great book – The Braddock Expedition and Fox’s Gap in Maryland!!!!!

The Carlyle House is fantastic! Great programs. The Lee-Fendall House works with them often.

This was a fascinating story with lots of research pored over to back up all that was found telling the story of this Civil War hospital! Helps tell the real story of the value of the medical personnel who worked to save the lives of the soldiers. Thank you!

I appreciate your feedback and I’m glad you enjoyed the article!

Thank you for sharing your knowledge and experience. I am curious about your opinion of the PBS series “Mercy Street,” which presented activity at Alexandria’s Mansion House Hospital. The series was inspired by actual events. I enjoyed the series.

Thank you so much! Yes, Mercy Street is an excellent show. While dramatized, it does paint a holistic picture of the various situations and demographics within the city at the time of the occupation.

Thanks. Quite interesting. I used to live near Camp Parole in Annapolis and don’t recall ever seeing this level of detail on the Camp, or the related hospital at the Naval Academy.

I bet there are records for Camp Parole – maybe hidden away in an archive like our hospital records! Sounds like a case for a historical detective.

Thanks for sharing this, Madeline. It was fun to learn more about the hospital record keeping systems you had to pore through.

Thanks so much, Neil! It was great to put pen-to-paper on my research journey.