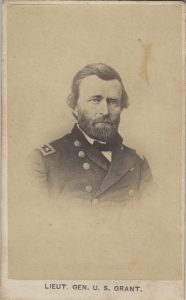

Stacking Arms “What Ifs?” – Episode II: “What If” Grant Had Shared Stonewall Jackson’s Fate During Grant’s Own Risky Nighttime Ride During the Appomattox Campaign?

“I, for one, began to grow suspicious.” Fearing treachery, “I cocked my pistol, and rode close behind him.” So wrote Lt. Col. Horace Porter, aide to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, about his fear that Grant was being led into a fatal trap by a Confederate uniform-wearing “scout” during a daring nighttime ride skirting Confederate lines during the Appomattox Campaign.[1]

“I, for one, began to grow suspicious.” Fearing treachery, “I cocked my pistol, and rode close behind him.” So wrote Lt. Col. Horace Porter, aide to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, about his fear that Grant was being led into a fatal trap by a Confederate uniform-wearing “scout” during a daring nighttime ride skirting Confederate lines during the Appomattox Campaign.[1]

Grant had chosen to put himself in this tense and dangerous situation on the night of April 5, 1865. Why? Because two of Grant’s top generals disagreed over how to bring Robert E. Lee and his fleeing army to bay, and the stakes were worth the risk to Grant’s life.

In organizing the pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia after its abandonment (on the night of April 2-3) of the Richmond-Petersburg lines, Grant had ordered a two-prong effort. The southern-most part was Maj. Gen. E.O.C. Ord’s Army of the James, supported by Maj. Gen. John G. Parke’s IX Corps, which followed the South Side Railroad. Between that force and the Appomattox River, Maj. Gen. George Meade, Army of the Potomac commander, led the II, V, and VI Corps of that army, preceded by Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s two cavalry divisions. Grant initially accompanied Ord’s column.[2]

On April 4, the advance of Lee’s army reached Amelia Court House. It expected to find desperately needed rations previously ordered there by Lee. But the food had not arrived. Lee spent the rest of the day at Amelia in a vain attempt to forage in the countryside while more of his men came in.[3] This delay gave Sheridan’s cavalry time to reach Jetersville, southwest of Lee and athwart Lee’s intended escape route into North Carolina. Realizing the importance of his position, Sheridan hurried forward what supporting infantry he could and began to entrench. Further, he sent a dispatch to Meade urging reinforcement, Sheridan’s messenger claiming that if Meade moved quickly, they could compel Lee’s surrender. This was the situation by nightfall on April 4.[4]

Meanwhile, on April 3 Meade had fallen ill, at times suffering “chills and fever, followed by nausea.” For the rest of the week Meade would travel by ambulance.[5]

On April 5, in response to Sheridan’s dispatch, Meade joined Sheridan outside Jetersville at about 1:30 p.m.[6] He continued to be so ill that he asked Sheridan to put Meade’s troops in position himself.[7] This is when a command conflict arose. Sheridan believed (correctly) that Lee was in the process of escaping to the west. Sheridan wanted to attack immediately. By contrast, not only was Meade convinced that Lee was massing at Amelia Court House, he refused to attack until all his forces were up. Moreover, Meade wanted to move on Amelia by his right flank, hitting Lee from the south and east. Sheridan saw this as striking what would be a vacuum, while facilitating Lee’s escape.[8]

Frustrated, Sheridan decided to go over Meade’s head. He wrote directly to Grant. The impetuous Sheridan stated that Lee would be captured “if we properly exerted ourselves,” tacitly suggesting that the proper exertion was not being made. Sheridan added a telling, fateful, coda: “I wish you were here yourself.”[9]

Sheridan entrusted his message to one of his “Jessie Scouts,” men who wore Confederate uniforms as they did daring work behind Confederate lines. A scout named Campbell, in “full Confederate uniform,” carried the message, which was written on tissue paper, then wrapped in tin foil and kept in the scout’s mouth for quick destruction if the need arose.[10]

It was nearly dark when the scout delivered Sheridan’s message. Grant immediately decided to heed Sheridan’s call and undertake a risky nighttime journey to confer with his subordinate.[11] At least sixteen miles stood between Grant and Sheridan, along a route that would take Grant perilously close to Confederate lines.[12]

Obviously, the situation called for a strong cavalry escort to protect the general commanding. Yet no cavalry was close at hand. Grant refused to wait. He insisted upon undertaking the trip with just his fourteen-member personal escort, plus four officers, including Porter, to accompany him.[13]

Grant later described his harrowing experience: “I had to make such a detour round the rebel lines that I rode at least thirty miles before reaching [Sheridan]. I remember being challenged by pickets, and sometimes I had great difficulty in getting through the lines. I remember picking my way through the sleeping soldiers, bivouacked in the open field. I reached Sheridan about midnight.”[14]

Porter vividly described the risks encountered: “I … questioned the scout about the trip, and found that we would have to follow some cross-roads through a wooded country and travel nearly twenty miles. It was now dark, but there was enough moonlight to enable us to see the way without difficulty. After riding for nearly two hours, the enemy’s camp-fires were seen in the distance, and it was noticed that the fence-rails were thrown down in a number of places, indicating that cavalry had been moving across this part of the country, though we were certain our cavalry had not been there.”[15]

As described in the opening of this post, during the journey Porter became worried about trusting his chief’s safety to a man in Confederate uniform.[16] Fortunately, the scout proved trustworthy. Campbell got them to Sheridan’s lines, but even then, there was danger in ensuring they made it through the picket line unscathed in the dark. “About half-past ten o’clock we struck Sheridan’s pickets. They could hardly be made to understand that the general-in-chief was wandering about at that hour with so small an escort, and so near to the enemy’s lines.”[17] Grant recounted in his Memoirs that it took “some little parley [to] convince[] the sentinels of our identity.”[18]

Grant conferred with both Sheridan and Meade and soon had the pursuit of Lee back well in hand. The next day, April 6, Lee would be brought to battle at Sailor’s Creek, losing a quarter of his army.[19] Grant’s risky nighttime ride had paid off handsomely.

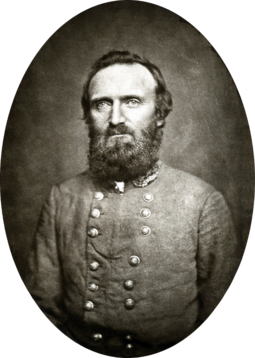

But the excursion could just as well have ended badly, not only for Grant personally but for the entire U.S. cause. What if Grant had in fact blundered into the nearby Confederate lines? Or what if roving rebel cavalry, the signs of which Porter had observed, had come upon Grant’s little group? Finally, as Grant’s mounted party approached Union lines, it faced the same risk that another lieutenant general and his escort had faced during their own moonlight ride some two years before. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s ride ended in his wounding and eventual death at the hands of his own men. Like Jackson, Grant was moving towards friendly lines, but from a direction only the enemy would be expected at that hour.[20]

What if Grant had been captured, wounded, or killed by Confederates, or wounded or killed by his own men? Regardless of how Grant was taken out of action, his absence from the scene, particularly at this critical stage of the pursuit of Lee, could have been disastrous.

At the time Grant decided to make his ride, Meade and Sheridan were at loggerheads. Indeed, that conflict appears to be why Grant took to the road. Without Grant to straighten things out, Meade presumably would have carried out his planned movement to envelope Amelia Court House from the south and east, allowing Lee more time to escape on April 6. Also, in his Memoirs, Sheridan stated that he had refused (presumably with Grant’s backing) to allow his cavalry to participate in “Meade’s useless advance,” instead starting them after Lee, catching up to his wagons around Sailor’s Creek. Sheridan had the VI Corps with him to help devastate Lee in the ensuing battle, because early on April 6 Grant had allowed Sheridan use of that corps.[21] But again, what if Grant had never arrived on the night of April 5?

If Grant had been wounded or killed trying to pass Sheridan’s pickets, would Meade then have asserted command over Sheridan? Then, in light of Meade’s belief that Lee was massing at Amelia Court House, would Meade have insisted that Sheridan’s cavalry stay to support him?

Such speculations take different avenues depending upon when Meade and Sheridan learned about Grant’s fate, whatever it was. If that fate involved an encounter with Confederates, it might have taken hours for a survivor of Grant’s party (if any) to report in. But learning that Grant had met with disaster, and/or simply learning that he had gone missing overnight, would have made finding the commander the top priority. Lee might have to wait, at least for the time being. In any case, the Union high command would have been distracted, to say the least.

Another alternative to consider involves Meade’s illness. Would the pressure of suddenly becoming top commander under such awful circumstances have further debilitated Meade, possibly rendering the pursuit of Lee cautious and sluggish? Or would he have turned over command to the hard-driving Sheridan? Even if not, would Sheridan, angered by the loss of his friend and patron Grant, have embraced an even more single-minded zeal to go after Lee, and end up being the man who had the glory of capturing, or more likely—considering Sheridan’s temperament—destroying the Army of Northern Virginia? We might not now be learning in history class about a dignified surrender at Appomattox Court House. But would history be writing about President Philip Sheridan?

[1] Horace Porter, Campaigning With Grant (The Century Co., New York, NY 1897), p. 455, https://archive.org/details/campaigningwith01portgoog/page/454/mode/2up.

[2] John R. Maass, The Petersburg and Appomattox Campaigns, 1864–1865 (Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 2015), p. 56, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-D114-PURL-gpo57106/pdf/GOVPUB-D114-PURL-gpo57106.pdf.

[3] Douglass Southall Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenants, Vol. III, pp. 689-691 (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, NY, 1942); Douglass Southall Freeman, R.E. Lee: A Biography, Vol. IV, p. 66-68 & Appendix IV-2 (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, NY, 1940); Rob Orrison, ‘“The only chance the Army of Northern Virginia had to save itself” – Jetersville, April 5, 1865’ (ECW Blog, April 5, 2015), https://emergingcivilwar.com/2015/04/05/the-only-chance-the-army-of-northern-virginia-had-to-save-itself-jetersville-april-5-1865/.

[4] Noah Andre Trudeau, “The Campaign to Appomattox,” National Park Civil War Series (Eastern National, 1995) (Section 2, entitled “Roads To Appomattox: A Desperate Race”), https://npshistory.com/publications/civil_war_series/6/sec2.htm#2; Burke Davis, To Appomattox: Nine April Days, 1865 (Eastern Acorn Press, reprint by Publishing Center for Cultural Resources, New York, NY, 1992), pp. 201-204.

[5] Davis, pp. 173, 201, 232, 266, 372; Porter, p. 453 (“Meade was quite sick, and had to take at times to an ambulance; but his loyal spirit never flagged, and all his orders breathed the true spirit of a soldier”). In an April 10 letter to his wife, Meade wrote: “I have been quite sick, but I hope now, with a little rest and quiet, to get well again. I have had a malarious catarrh, which has given me a great deal of trouble.” Meade to Margaretta, April 10, 1865, reproduced by Thomas Huntington in Searching for George Gordon Meade, The Forgotten Victor of Gettysburg, https://searching4meade.com/2015/04/10/a-great-contempt-for-history-april-10-1865/.

[6] Davis, p. 232.

[7] Philip Sheridan, Civil War Memoirs (Bantam Books, New York, NY, 1991), p. 335.

[8] Davis, pp. 231-233; Sheridan, pp. 335-336. In his Memoirs, Grant revealed whose approach he favored. Grant noted that “[Sheridan] wanted to attack, feeling that if time was given, the enemy would get away; but Meade prevented this, preferring to wait till his troops were all up.” Ulysses S. Grant, John F. Marszalek with David S. Nolen and Louie P. Gallo, Eds., The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant: The Complete Annotated Edition (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2017), p. 708.

[9] Porter, p. 454.

[10] Trudeau, “Sheridan’s Scouts,” https://npshistory.com/publications/civil_war_series/6/sec2.htm#2; Porter, p. 454.

[11] Porter, p. 454.

[12] In his Memoirs, Grant said that the trip was sixteen miles. Porter said that Campbell told him that it would be “nearly twenty,” considering the route that would have to be travelled. Grant, p. 708; Porter, p. 455.

[13] Porter, p. 455.

[14] John Russell Young, Around The World With General Grant: A Narrative Of The Visit Of General U. S. Grant, Ex-President Of The United States, To Various Countries In Europe, Asia, And Africa, In 1877, 1878, 1879: To Which Are Added Certain Conversations With General Grant On Questions Connected With American Politics And History(Subscription Book Department, American News Co., New York, NY 1879), Vol. 2, p. 302, https://archive.org/details/aroundworldgrant02younuoft/page/302/mode/2up?q=lee.

[15] Porter, p. 455.

[16] Porter, p. 455.

[17] Porter, p. 456.

[18] Grant, p. 709.

[19] Grant, p. 709; Porter, p. 456; “Sailor’s Creek (Sayler’s Creek),” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/sailors-creek.

[20] James I. Robertson, Jr., Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend (Macmillan Publishing USA, New York, NY, 1997), pp. 726-729.

[21] Sheridan, pp. 337-339.

Interesting premise. If Grant became ‘incapacitated’, or “gone missing”, or dead, because of Sheridan’s appeal for him to “come visit”, I would think that would be a tremendous blow against any command aspirations Sheridan had, especially with Meade as his superior, and the fact that Sheridan went over his head to get Grant moving and hence place him in danger.

My compliments on this superbly written and deeply researched little gem — nicely done … what I find most interesting about your piece, however, is it highlights the close relationship that Grant had with Sheridan … so, when Sheridan commented “I wish you were here”, Grant, clearly knowing what was at stake, didn’t wait second … he rode off into the darkness, found Sheridan, got briefed on the situation, and visited Meade’s HQ and gave him written tactical direction … Grant didn’t do that often, but he clearly understood the AOP’s huge opportunity and decided to take the risk … this is what great commanders do. For the reader who wants to know more about Grant’s thinking on this matter, see Note 14, pp 301-303.

Seconding Mark Harnitchek’s words. Great article, clearly written, well researched, giving a buffet of food for thought. I’m left thinking, that’s what Meade gets for not writing his memoirs and dying only 7 years after the war, his side of things gets under-reported.