Martial Law in 1862 Charleston

ECW welcomes back guest author Walt Young.

President Abraham Lincoln’s use of martial law, among other wartime restrictions on civil liberties, has been one of the most controversial aspects of the American Civil War. His actions were contested by many loyal Unionists and were used by pro-Confederate sources to depict him as a tyrant.

Yet similar scrutiny can be placed on actions of the Confederate government. How would a government which claimed to support limits on central authority handle the complexities, struggles, and paranoia of war? We can use the Confederacy’s founding city, Charleston, as a study of how martial law in the South would impact its citizens – and the large proportion of Southerners held without rights at all.

From its beginning, the Confederate government publicly embraced democracy. In his inaugural address, Confederate President Jefferson Davis declared that “our present condition, achieved in a manner unprecedented in the history of nations, illustrates the American idea that governments rest upon the consent of the governed.”[1]

However, by 1862, the Confederacy had not walked the pro-democratic walk, even for its white citizens. In November 1861, the Confederacy held a presidential election with only one major candidate, Jefferson Davis. Davis had already been selected by the “provisional” Confederate congress in March, so the typical voter was left with little choice in November.[2]

Meanwhile, in South Carolina, the state’s secession convention – the first institution to announce secession – created an Executive Council in late 1861. This body consisted of the elected governor and lieutenant governor, but also three other politicians. The council was given sweeping mandates to declare martial law, “arrest and detain all disloyal or disaffected persons,” and seize property. Neither South Carolina’s voters nor its elected legislature had created or exercised control over the council.[3]

In this undemocratic environment, the Confederacy faced several major challenges by spring 1862. The economic problems which would bedevil the Confederacy had begun, including what would soon be runaway inflation. As a result, speculators and merchants faced blame for raising prices. Meanwhile, the war’s battles and effects accelerated. In South Carolina, U.S. troops had taken control of Beaufort and were moving toward Charleston.

Both the national Confederate government and the state of South Carolina began to impose controlling measures. On February 27, 1862, Confederate Senator Louis Wigfall “reported a bill to authorize the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus in certain cases,” as well as authorizing Davis to declare martial law. The senate had no public debate on this question, passing the bill in a secret session before it became law.[4]

In South Carolina, the Executive Council soon declared martial law. The official order by Governor Francis Pickens, dated May 2, 1862, stated that “Martial Law is hereby established and proclaimed in and over the city of Charleston.” The declaration also suspended habeas corpus, and delegated power to the Confederate army “to impress labor of all kinds for public works and defence [sic]” in areas south of the Santee River.[5]

The Charleston Daily Courier had advocated for martial law, writing that it would “relieve us from the intolerable oppression which monopoly and extortion have brought upon us.” An aligned letter to the editor referred to merchants who raised rice prices as “Shylocks,” dismissing explanations of scarcity. Meanwhile, a Columbia paper supported martial law for the purpose of cracking down on “men with strong Northern sympathies,” writing that martial law “seems to be the most practicable and effectual mode of cracking down on the enemy at home.”[6]

There were three major categories of Confederate edicts in Charleston. The first was a heavy economic hand. The military government of Charleston prevented sales of liquor and salt, denied the ability to gain a fishing license, and enforced a cotton embargo. The embargo, which sought to pressure Great Britain into recognizing the Confederacy, had a lasting negative impact on the South’s economy. Historian Sven Beckert writes that “exports to Europe fell from 3.8 million bales in 1860 to virtually nothing in 1862,” and the intended diplomatic effects went unrealized.[7]

A second category of proclamations controlled travel. Passports were required to depart the city, and both city newspapers criticized a haphazard rollout of the passport program. However, the beginning of martial law coincided with a public failure of Confederate control.[8]

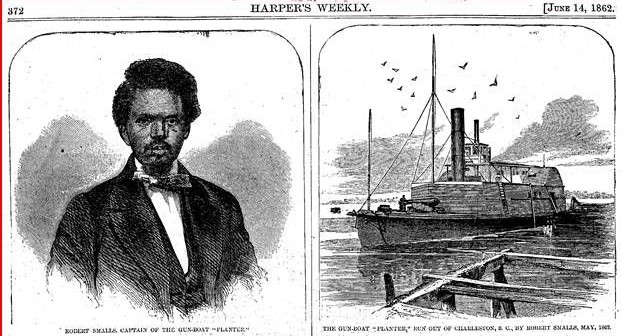

On the night of May 13, 1862, Robert Smalls, an enslaved man on the Confederate contracting ship Planter, piloted the vessel to escape through Charleston Harbor with 15 others. This was the second such escape from slavery in three weeks and cost the Confederates military intelligence, cannons, and the “incalculable injury” of proof that escape was possible. Several martial law measures responded to the escape, including removal of “idle” enslaved workers, crackdowns on black people’s travel, and restrictions on departure points for outgoing ships. The Planter’s three white officers, whose absence from the ship accidentally allowed the escape, were court-martialed in early August.[9]

The third category was the forced impressment of labor to work on harbor defenses up and down the coast. Orders forcing enslaved workers into these roles continued throughout the war. While enslavers were given compensation for the taking of their “property,” the actions drew opposition.

In August 1862, a group of delegates from Abbeville, SC, petitioned the Executive Council. Their objections exemplify the contradictory nature of pro-slavery ideology: stated concern for enslaved workers’ health and nutrition, worries about inability to harvest, and the danger of “contamination and consequent ills which would result from…large bodies of negros congregated under lax discipline.” This “contamination” was likely the idea of freedom.[10]

Martial law did not last forever. By August 1862, the city’s newspapers turned on the idea and on the Executive Council. Criticisms included destructive behavior by Confederate soldiers, the “too rigorous” enforcement of the passport system, and the lack of democratic accountability for the Executive Council. Martial law in Charleston was rescinded, both by local military authorities and Governor Pickens, on August 19-20, 1862. The Executive Council was dissolved by the end of 1862.[11]

Enslavement inside Charleston’s forts outlived martial law, and expanded throughout the war as conditions worsened. In 1863-64, over 3,000 enslaved workers were forced to work on forts that were being destroyed by cannon fire.[12]

The story of martial law in Charleston illustrates contradictions within Confederate ideology. The leaders of the Confederate government had argued for limited central power, a hands-off approach to trade, and a strident defense of slavery. And yet, within two years of seceding and taking power, they had created undemocratic systems, aggressive and counterproductive seizures of exports, and massive impressment of enslaved workers. Meanwhile, newspapers which cheered on potential seizures of power when directed at others had second thoughts when seeing them up close.

Martial law also illustrates the Confederacy’s authoritarianism regarding enslaved workers. Rhetoric of Confederate liberty rang hollow with the 57 percent of South Carolinians held in slavery, particularly as they were forced to rebuild the crumbling forts of their enslavers. In seeking governmental control of the enslaved population, the Confederacy continued a longstanding pattern: protecting the existence of the slave system could justify almost any vice.

Walt Young has loved learning about the Civil War since visiting Harpers Ferry, West Virginia on a childhood trip. When not studying history, he enjoys hikes, mysteries, and Baltimore sports.

Endnotes:

[1] Jefferson Davis, “First Inaugural Address”. February 18, 1861, Montgomery, AL. https://jeffersondavis.rice.edu/archives/documents/jefferson-davis-first-inaugural-address

[2] The only available number for the 1861 Confederate election results allegedly reflects only the total votes in North Carolina, totaling over 47,000. Further results are unclear, with this 1959 journal article commenting on “historians’ lack of data” about the election.

[3] “Journal of the Convention of the People of South Carolina”. Columbia, SC, 1862, 793-796. Cited by Eric Lager, “RADICAL POLITICS IN REVOLUTIONARY TIMES: THE SOUTH CAROLINA SECESSION CONVENTION AND EXECUTIVE COUNCIL OF 1862,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2008.

[4] “The Confederate Congress,” The Charleston Mercury, March 3, 1862.

[5] “Proclamation of Martial Law,” The Charleston Daily Courier, May 5, 1862.

[6] “The Columbia Prisoners,” Courier, March 11, 1862; “Extortioners and Speculators,” Courier, April 5, 1862; “Extortionists,” Courier, April 8, 1862.

[7] “The Regulations of the Provost Marshal Under Martial Law,” Mercury, May 12, 1862; “Martial Law,” The Courier, May 26, 1862; “Order No. 9,” Courier, June 18, 1862; Sven Beckert, “Emancipation and Empire: Reconstructing the Worldwide Web of Cotton Production in the Age of the American Civil War”. The American Historical Review, Dec. 2004, 1405-1438.

[8] “Only Two Hours for the Issue of Passports,” Courier, May 14, 1862; “Martial Law,” Courier, May 30, 1862.

[9] “Disgusting Treachery and Negligence,” Mercury, May 14, 1862; “Notice,” Mercury, May 16, 1862; “Martial Law,” Courier, May 19, 1862; “The Case of the Stolen Steamer Planter,” Mercury, Aug. 1, 1862.

[10] “The State of South Carolina – Abbeville District,” Mercury, August 22, 1862.

[11] “Respect for Property,” Courier, August 22, 1862; “Martial Law and the Passport System,” Courier, August 7, 1862; “The Executive Council,” Courier, August 25, 1862; “State of South Carolina,” Courier, August 23, 1862.

[12] “Confederate Slave Payrolls Reveal Details about the Lives of African-Americans during the Civil War.” National Park Service, April 23, 2022. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/confederate-slave-payrolls-charleston-harbor.htm

While reading this excellent, informative article, the following thoughts sprung to mind: “The ends justify the means…” Do as I say, not as I do… “All is fair in love and war.” And the biggest lesson: if one is going to push the boundaries during wartime, make certain you win.

Excellent and timely piece that gives balance and perspective to the tired rants of neoConfederates who chastise Lincoln as a tryrant for using executive power for national security concerns during wartime. Those of us who have studied Southern Unionists can point to numerous examples of Confederate legislators denouncing the Davis administration for unconstitutional or unlawful executive actions during the Civil War. These days it seems that presidents of both parties declare pseudo national emergencies to implement executive orders of questionable legality or that are blatantly unconstitutional. The Civil War was an existential crisis and National emergency that could justify such abuses of power in the eyes of many North and South. Both Davis and Lincoln might blush at some of the many executive orders from Obama, Trump, Biden, and Trump that have little justification compared to the challenges that faced our wartime chief executives.

Great article. Let’s also recall that Charleston made many people wear identifying badges so that they would not be arrested for being escaped slaves.

Thank you for this enlightening view of martial law in Charleston, SC, and other controlling methods imposed by Jefferson Davis and Governor Pickens.

I have studied the Civil War for over 30 years and published “The Civil War In My South Carolina Lowcountry” several years ago. I do not dispute the author’s points in his article. I do, however, would have preferred that he not lightly skip over Lincoln’s use of many pressing restrains imposed against the United States citizens. It seems to me that all professional historians continue to seeep under the rug and ignore the many authoritarian tactics Lincoln used after he started the war. I have followed ECW for a long time and enjoy reading it daily. I do wish there could be more articles about the Confederacy other than fanning the flames of the Lost Cause myth.

Boo hoo.

Why can’t an article focus on just one? It’s a short summary, not a book.

If this article only talked about Lincoln’s overreach, would you have come here and commented complaining that it didn’t talk about Davis? Awful bold of you to come and complain about something that someone else provided for free. If you don’t like it, you can write and submit your own guest article to ECW about whatever you want.

Great article on a little known period in Confederate Charleston. I never knew many things in this article. How ironic that enslaved were upset over forced impressment of their human property by the very government they formed. More please!

Hate autocorrect….enslavers not enslaved