A Long Time Coming: The Trans-Mississippi Surrenders of Confederate Generals M. Jeff Thompson, Kirby Smith, and Stand Watie

In school, many learn that the Civil War ended when Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee – having found his army surrounded with no chance of escape – surrendered his 28,000 troops to Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia on April 9, 1865. Perhaps they learn, too, about Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnson two weeks later surrendering to Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman at Bennett Place near Durham, North Carolina in the largest surrender of the war.

Certainly, those two surrenders brought an end to most of the fighting in the country, but not all. There were still Confederate generals in the west – such as M. Jeff Thompson, E. Kirby Smith, and Stand Watie – who vowed to continue fighting. And there were still many questions to answer in states such as Missouri as to how guerrilla fighters would be treated.

In my book A State Divided: The Civil War Letters of James Calaway Hale and Benjamin Petree of Andrew County, Missouri, the final chapters address this ongoing conflict, describe the difficulties of getting news to the soldiers still fighting in the field, and explain those final Trans-Mississippi surrenders. Much of what follows is excerpted from my book, but be sure to check out A State Divided if you want a more complete picture.

Prior to Lee’s surrender, Confederate President Jefferson Davis, along with his cabinet, fled the capital city of Richmond, one day before its fall. While most Confederate commanders admitted the war was at an end and laid down their arms soon after Lee’s surrender, Davis and his cabinet vowed to continue fighting. Into early May, Davis and a few other Confederate commanders and political leaders – mostly in the Trans-Mississippi Theater – were still urging Confederates to fight through means of guerrilla warfare. A lot of that fighting was happening in and around Missouri.

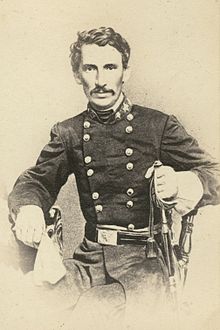

It took many weeks for the news of the surrenders in the east to reach Confederate troops and guerrillas still active in the west. One of those who continued fighting was the former mayor of St. Joseph, Missouri, M. Jeff Thompson, now commander of the Northern Sub-District of Missouri. Finally contacted in Arkansas by Union commanders offering him the same terms given to Lee if he would surrender, Thompson sent the following reply:

Harrisburg, Arkansas, April 30, 1865

Maj. Gen. J.J. Reynolds, U.S. Army,

Commanding U.S. Forces in Arkansas, Little Rock, Ark.:

General:

Your favor of the 18th instant, inclosing a copy of your communication to Maj. Gen. J. F. Fagan, has this instant reached me. Being disposed to believe that you are actuated by philanthropic principles in making these propositions, or are acting in conformity to orders, I receive them in more kindness that I otherwise would, but I respectfully and most positively decline accepting your offer. While frankly admitting that the news that has reached me of the condition of the Confederate cause in Virginia is very discouraging, yet believing firmly in the justness of our cause and our ability to succeed in the course of time, I will march firmly on in the path of my duty until my Government or superior officers shall bid me stop, which I hope and pray will never be until the Southern people are a free and independent nation. I regret exceedingly the necessity of sacrificing more “brave men,” and mourn for the suffering of our people, but it seems only thus that it is possible to gain our independence, and we must meet the shock and bear the brunt as our forefathers did in ’76, and I therefore cheerfully bear my portion of “the responsibility” and will abide the consequences.

I have the honor to be, general, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

Jeff Thompson, Brigadier-General, Commanding

P.S. Allow me to express my sincere regret and horror at the manner in which President Lincoln came to his death. [1]

As late as May 5, according to one official letter, both Thompson and Maj. Gen. James Fleming Fagan, who commanded the District of Arkansas, declined to surrender. Just a day later, however, Thompson was reported to be on his way to Jacksonport with a flag of truce. On May 10, Lt. Col. C. W. Davis in Chalk Bluff, Arkansas, wrote to Maj. Gen. Grenville Dodge, commander of the Department of the Missouri: “Brig. Gen. Jeff Thompson is in our camp. He is a witty fellow, and is continually talking about impossibilities. He has not yet decided whether to surrender or not. Shall try to convince him. If he gives up it will [be] hard to find his army.” [2]

Davis must have been persuasive, for on May 11, Thompson surrendered his troops to Dodge – at least those who had not deserted or fled with Gen. Joseph O. Shelby and Gen. Sterling Price to Mexico rather than surrender. They were paroled on May 29 at Jacksonport and June 5 at White River in Arkansas, with some bushwhackers hiding out in northern Arkansas likely taking advantage of the opportunity to surrender as part of his command.

Confederate deserters presented another dilemma for Union forces. In a letter dated April 26 from Pine Bluff, Arkansas, Brig. Gen. Powell Clayton presented his current situation and questioned how to proceed: “I have the honor to state that deserters from the rebel army are coming into this post at the rate of five per day. A majority of these men are utterly destitute. Many of them claim to have been conscripted by Price during his raid into Missouri, and to have homes in that State, to which they are anxious to return. Others again wish to return to their farms in this State and raise a support for their families. The remainder seem uncertain what to do, but express a willingness to go any place where they can find employment. They are all anxious to take the oath and leave the rebel army. I respectfully ask instructions as to what disposition shall be made of these men. Shall I form them into camps here and furnish them subsistence, forward them to Little Rock, or give them transportation to any points north which they may elect?” [3]

Many guerrillas simply headed north, and reported bushwhacker sightings poured in, describing their suspected movements and criminal acts, as well as recounting the number killed, for many became targets upon their return. Some Missourians wanted these guerrillas banned from returning to their home counties and even wrote letters to officials demanding that they be forced to move south rather than be allowed to return. Local leaders, fearful of guerrilla activity, called upon military leaders to send troops, but many were told it was time for civil authorities to take charge.

There was also confusion among Union leaders as to how guerrillas should be treated. In a letter dated May 7, Maj. Gen. G.M. Dodge in St. Louis wrote to Col. Chester Harding, Jr., advising: “In reference to your letter relative to bushwhackers who desire to give themselves up, you can say to all such who lay down their arms and surrender and obey the laws that the military laws will not take any further action against them, but that we cannot protect them against the civil law should it deem best to take cognizance of their cases. It is useless for them to continue the contest, and sooner or later they will be caught, and no terms will be granted them.” [4]

The majority of guerrillas surrendered peacefully. Others, like notorious Missouri guerrilla leader William Clarke Quantrill, who had led the infamous attack on Lawrence, Kansas, did not. Guerrillas like Quantrill faced a dilemma: “Public opinion had turned against the raiders. Considered guerrillas and not recognized as legitimate soldiers, Quantrill’s men were denied the general amnesty offered to the Confederate army upon Lee’s surrender. Viewed as outlaws, Quantrill’s men faced certain death if captured in Missouri.” [5] Quantrill was shot in Kentucky on May 10 and died one month later.

A letter from Maj. Gen. James G. Blunt to Dodge on May 16 reported on twenty rebels, formerly of Quantrill’s band in Kentucky, crossing the Arkansas River and heading toward Missouri. He had spoken to two deserters, whom he described as “intelligent and apparently truthful men,” who said these rebels were “going north into Missouri … to pursue a relentless guerrilla warfare, private revenge and plunder being their motive.” [6]

Guerrillas such as Archie Clement, Frank and Jesse James, and Cole and Jim Younger did exactly that, with many of their bank robberies targeting people and institutions who supported the Union.

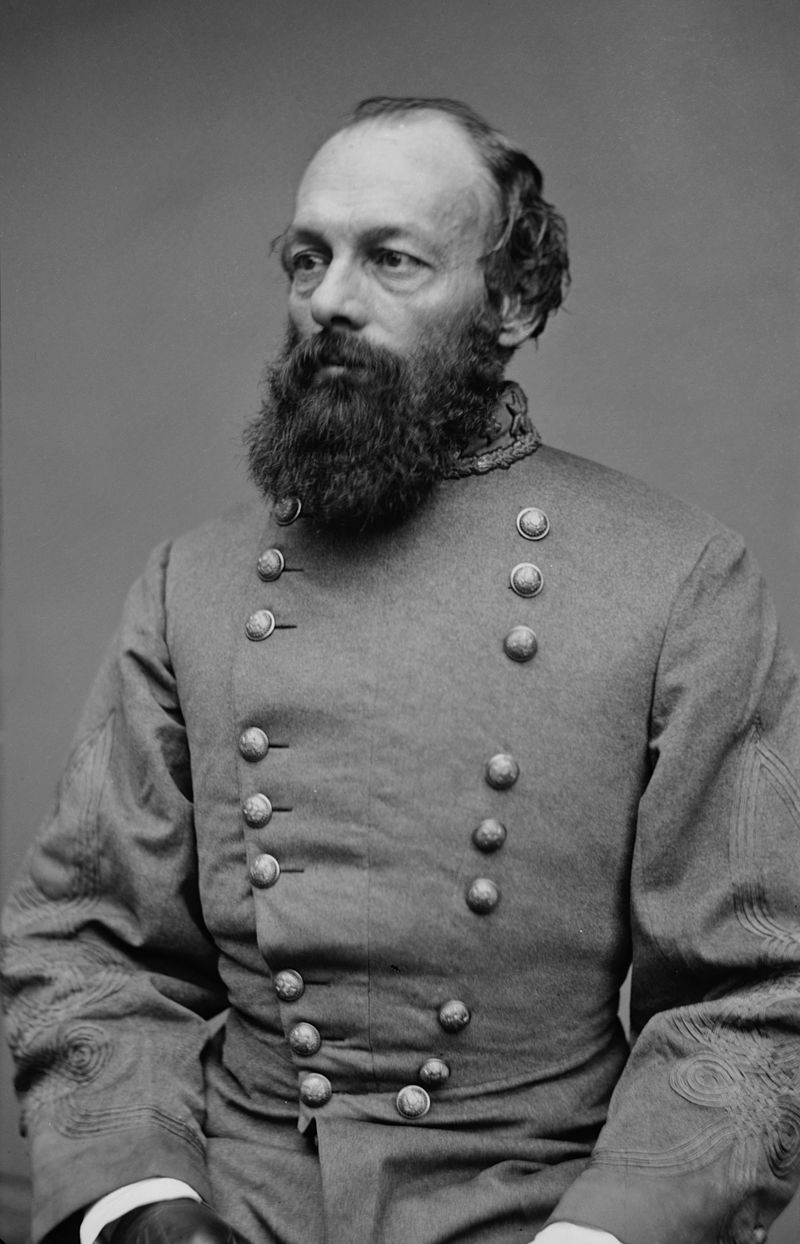

As late as May 16, according to a letter from Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace to Grant, “General E. Kirby Smith … refused to surrender and urged his soldiers to hold out, as they have means to maintain themselves until assisted from abroad.” [8]

Even more, according to Wallace, Smith was suspected of having secret negotiations with Maximilian I, an Austrian archduke who became emperor of the Second Mexican Empire in 1864. Wallace told Grant, “I cannot do otherwise than believe that there is a secret arrangement existing between the Mexican Imperialists and the Texan Confederates, contemplating ultimate annexation of Texas and mutual support, or the support without the annexation.” [9]

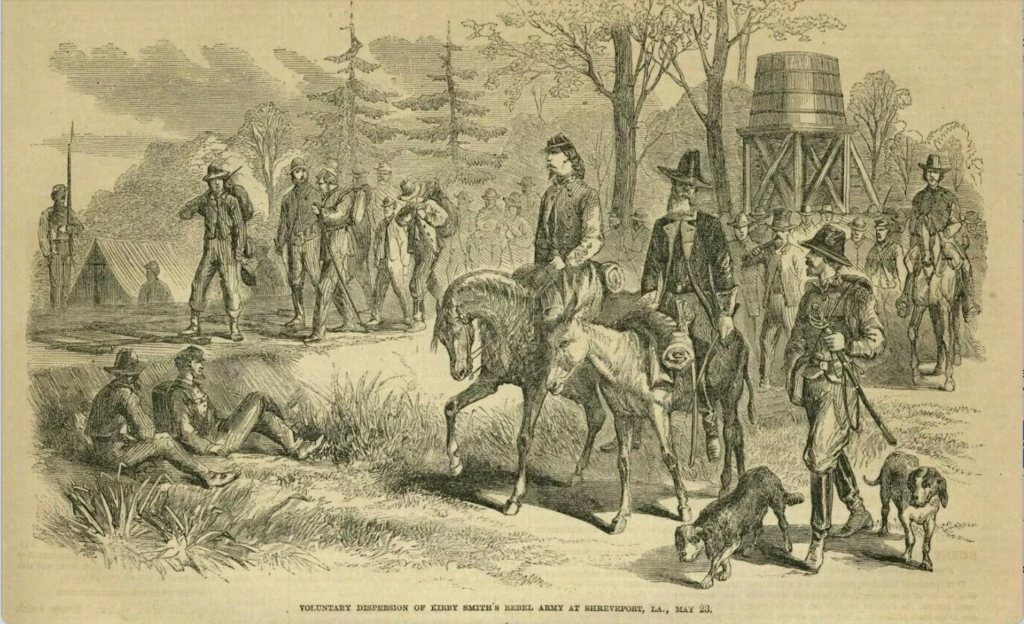

Such an annexation never happened, though, and Smith, the last Confederate general with a large army, finally surrendered to Union Gen. Edward Canby in New Orleans, Louisiana, on May 26. Smith had served as commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, which included Arkansas, Missouri, Texas, western Louisiana, Arizona Territory, and the Indian Territory.

The surrender was actually arranged by Confederate Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, acting on Smith’s behalf since Smith had already left Louisiana for Texas. On June 2, Smith signed the terms of surrender in Galveston, Texas and laid down his arms before fleeing to Mexico to avoid being prosecuted for treason. He later fled to Cuba, but eventually returned to Virginia in November 1865 to sign the amnesty oath.

Smith’s troops, totaling 43,000 at the time of his surrender, had been cut off from other Confederate troops since the capture of Vicksburg, which gave the Union control of the Mississippi River. Their last-ditch effort to invade Missouri under Gen. Sterling Price in the fall of 1864 had been a failure. Now, they, too – dejected and despairing but alive – were anxious to rejoin their families. However, many no longer had homes to return to.

It was not until Federal troops arrived in Galveston on June 19 that slaves in Texas learned they were free, a day now commemorated by Juneteenth celebrations. And it was not until four days later that the last Confederate general, Cherokee Stand Watie, finally surrendered.

The only American Indian to attain the rank of brigadier general during the Civil War, Watie had been “so committed to the Southern cause that he refused to acknowledge the Union victory in the waning months of the Civil War,” and he kept his troops in the field for nearly a month after Smith’s surrender. [10]

A full 75 days after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, on June 23, Watie laid down his arms, surrendering his battalion of Creek, Seminole, Cherokee, and Osage Indians to Union Lt. Col. Colonel Asa C. Matthews at Doaksville near Fort Towson in Choctaw County, Oklahoma.

Endnotes:

- “Louisiana and the Trans-Mississippi – Chap. LX.” The Official Records, Series 1, Volume 48, Part 2, page 249, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924077723025&view=1up&seq=197.

- Ibid, pg. 386.

- Ibid, pg. 207.

- Ibid, pgs. 341-2.

- Green, Rodney J. “The Man Who Killed Quantrill • Missouri Life Magazine.” Missouri Life Magazine, https://missourilife.com/the-man-who-killed-quantrill/.

- “Louisiana and the Trans-Mississippi – Chap. LX.” The Official Records, Series 1, Volume 48, Part 2, page 472, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924077723025&view=1up&seq=197.

- Harris, Kathleen. “25 little known facts about the outlaw Jesse James.” Whizzpast, 21 July 2014, https://www.whizzpast.com/25-little-known-facts-about-the-outlaw-jesse-james/

- “Louisiana and the Trans-Mississippi – Chap. LX.” The Official Records, Series 1, Volume 48, Part 2, page 457, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924077723025&view=1up&seq=197.

- Ibid.

- Pruitt, Sarah. “The Last Confederate General to Surrender Was Native American.” History, A&E Television Networks, 12 July 2023, https://www.history.com/news/stand-watie-cherokee-confederate-civil-war-general.