Stacking Arms: What If Capturing the Enemy Isn’t the Objective?

Over the last few weeks, Emerging Civil War has been exploring the surrender of Civil War armies through our Stacking Arms series. For four bloody years, Civil War generals sought to force opposing armies to lay down their arms. Most battles were indecisive, but the mileposts of the Union’s road to victory in the Civil War were the surrender of significant Confederate forces: Fort Donelson, Vicksburg, Appomattox. Even great victories like Gettysburg were dimmed, at least in the eyes of civilian leadership, when the defeated armies escaped without being captured or destroyed.

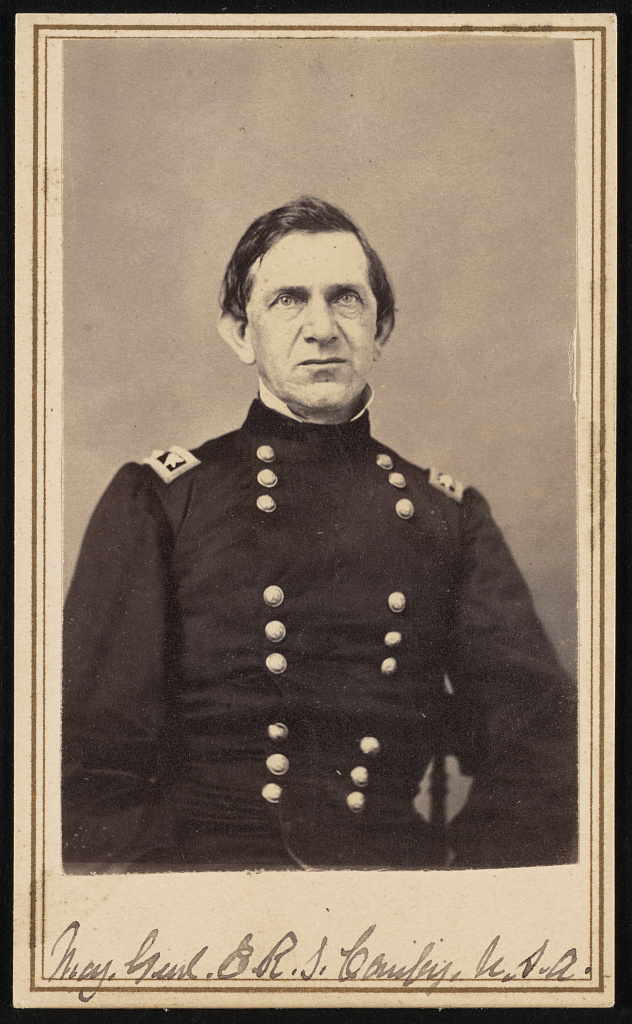

But imagine a commander who might be intentionally avoiding the capture of an enemy army. While it seems outlandish, there’s reason to believe that when he had Confederate forces on the ropes, Union Colonel Edward R.S. Canby preferred that the Rebels continue to retreat instead of surrendering to him.

In late 1861 and early 1862, around 3,000 Confederate cavalry with a handful of light mountain howitzers rode west across Texas and into what was then the New Mexico Territory – or, if you asked them, at least partially the Confederacy’s Arizona Territory. They sought to expand the Confederacy’s borders into the Rocky Mountains, with its extensive mineral resources, and to the Pacific Coast, to evade the tightening Union blockade of Atlantic ports.

Led by Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley, the Confederates saw some early success. Lieutenant Colonel John Baylor had paved the way, capturing several hundred Union troops in 1861 and establishing a nascent Confederate government centered around Mesilla. From there, Sibley rode north along the Rio Grande River, defeating Canby in a pitched battle at Valverde in February 1862. Canby retreated into Fort Craig, and without the supplies to conduct a siege, the Confederates continued north.

Despite winning another tactical victory at Glorieta in March, they lost their supply train to a column of Colorado volunteers. At this point, Sibley’s small army was already worn down by months of hard winter campaigning through hundreds of miles of Southwestern desert. Weather, disease, and two pitched battles had taken their toll, and he now had no choice but to begin withdrawing south. As they pulled out of the capital of New Mexico, the Santa Fe Gazette described the Confederates as “in the most destitute condition in regard to the most common necessities of life.”[1] Even Texas Lt. Col. W.R. Scurry of the Fourth Texas Cavlary called his own troops “crippled” by supply shortages.[2]

At first, Canby seemed to pounce on the opportunity. He sallied out of Fort Craig, and summoned reinforcements from Fort Union – the same troops that had just fought at Glorieta, and burned Sibley’s wagon train. Uniting his forces outside Albuquerque, he aggressively pursued Sibley down the Rio Grande.

In mid-April, Union forces surprised the Confederates at the sleepy hamlet of Peralta. The small town’s adobe buildings doubled as ready-made fortifications. After Sibley’s outnumbered Texans dug in, Canby declined to launch an immediate attack. After hours of maneuvering, skirmishing, and trading artillery fire, the day’s cold, fierce, desert wind turned into a raging sandstorm that made more fighting impossible. There would be no climactic battle that day, and Confederate troops slipped away in the night.[3]

After Peralta, it feels like something changed in Canby’s calculus. Instead of pursuing aggressively, he followed the disintegrating Confederate army at a careful distance. For several days, the two armies marched parallel to one another, the Confederates on the western bank of the Rio Grande, and the Union column in plain view on the eastern bank.[4]

By this point, Union forces were succumbing to the same wear and tear of desert campaigning that had crippled Sibley’s army. From broken down horses to exhausted men and dwindling rations, the New Mexico Territory’s military and civilian leadership sent a clear and unified message to Washington that they were at the end of their rope. Territorial Governor Henry Connelly reported that, “The cavalry and means of transportation on both sides are completely broken down, and neither a retreat nor pursuit can be effected with any degree of rapidity. The Territory has been completely exhausted of grain on the route of the military movements, and nothing can be obtained of forage for animals.”[5]

Stranded in an unforgiving desert, hundreds of miles from safety or supplies, Sibley’s bedraggled army should have been easy pickings. At first, rank and file Union soldiers were frustrated by Canby’s perceived timidity. Many of them had rushed volunteer, convinced like so many early Civil War recruits that one good fight would decide the war. These volunteers suffered through hundreds of miles of marching and two tactical defeats at Valverde and Glorieta. At Peralta, they knew they had the advantage in numbers, but in their view, Canby was a Regular Army administrator whose West Point training kept him from acting aggressively enough. Ovando Hollister, of the 1st Colorado Volunteers and a veteran of the battle of Glorieta, fumed in his diary that, “While the regulars fight to avoid fighting the volunteers fight to whip.”[6]

Maybe most importantly, food wasn’t just scarce for Sibley’s Confederates. Canby’s troops had survived while holed up in Fort Craig by dramatically reducing rations. One Colorado volunteer’s diary is a near-constant complaint about the quality and quantity of food he was receiving during that time. Well after the war, a veteran told the Denver Post that he confronted Canby about the lackluster pursuit to destroy Sibley’s army. In response, Canby reminded him of the Union forces’ scant rations, and stated that if they took the Confederates prisoner, “we’d all starve, and that’s why I’m not following them.”[7]

We should take any single post-war account with a grain of salt. It’s impossible to know for sure what any general’s intentions were, and we have even fewer clues than usual with Canby. He was killed shortly after the Civil War, and left behind no memoirs to illuminate his reasoning.

But the story raises an interesting and plausible question: In the heart of a desert so remote and unforgiving that it’s called the Jornada del Muerto – Dead Man’s Journey – was it realistic for worn down Union forces to capture, guard and feed even a small Confederate army? Or was Sibley’s escape from New Mexico just one in a long line of Civil War campaigns that was destined to end without either side actually being captured or destroyed?

[1] “Military events in New Mexico,” Santa Fe Gazette, April 26, 1862.

[2] United States. War Records Office, et al.. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union And Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume IX, Chapter XXI. 1880, 542.

[3] Hollister, Ovando James. Boldly They Rode: A History of the First Colorado Regiment of Volunteers. The Golden Press. 1949, 95; Thompson, Jerry. Civil War in the Southwest: Recollections of the Sibley Brigade. Texas A&M University Press, 2001, 105; Hall, Martin Hardwick. Sibley’s New Mexico Campaign. University of New Mexico Press. 1960, 130.

[4] Mumey, Nolie. Bloody Trails Along the Rio Grande: A Day-by-day Diary of Alonzo Ferdinand Ickis. The Old West Publishing Company. 1958. 55; Hollister, Ovando James. Boldly They Rode: A History of the First Colorado Regiment of Volunteers. The Golden Press. 1949, 99; Thompson, Jerry. Civil War in the Southwest: Recollections of the Sibley Brigade. Texas A&M University Press, 2001, 119.

[5] United States. War Records Office, et al.. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union And Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume IX, Chapter XXI. 1880, 552, 663.

[6] Hollister, Ovando James. Boldly They Rode: A History of the First Colorado Regiment of Volunteers. The Golden Press. 1949, 84.

[7] Whitlock, Flint. Distant Bugles, Distant Drums: The Union Response to the Confederate Invasion of New Mexico. University Press of Colorado. 2006, 234.

Vanby in the Southwest seemed like one of the Austrian generals of the 18th Century, who only went on the offense for defensive purposes.

He was never aggressive like a Lee or a Jackson, but I think Canby gets a bad rap. Very few other commanders had to operate with the logistical constraints he had in New Mexico, especially that early in the war. And at least one planned offensive in 1862 was preempted by the final Confederate withdrawal back into Texas.

What if you have no means of guarding them, caring for them, or feeding them?