Who Were the “Scalawags” & Why Were They Persecuted By The Klan?

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome back Patrick Young, author of The Reconstruction Era blog.

When I was a child I first heard my grandfather use the term “scalawag” in referring to me! He did not mean to insult me. For grandpa, it was an accurate description of a child acting on his impulses no matter what adult expectations were. The word “Scalawag” traces its origins back to the name of the village Scalloway in the Shetland Islands. Its original meaning is obscure, but it came to be used by the English and Scots to refer to a useless or a wicked person. Being Irish, my grandfather did not have a negative view of the Shetlands and so he used it as many Irish did to describe a funny person who did not always live his life in accord with social expectations.

The word was adopted in the United States beginning in the 1830s and by the time of the Civil War it was commonly used as a sobriquet attached to someone’s name who was not in good repute. By the end of the Civil War, it became a demographic category of people who were born in the South who did not support the Confederacy. Nearly 100,000 men Southern white men had fought in the Union Army against the Confederacy. Since approximately 750,000 to a million men fought for the Confederacy, that means that 10% to15% of the military-aged men were likely “Scalawags.” Of course, there were even more Southern Blacks who fought for the Union, but they are never called “Scalawags.” Because the Confederacy was based on a racial solidarity among white Southerners, Blacks could be viewed as enemies in Reconstruction, but not traitors.

By 1867, as the Ku Klux Klan saw phenomenal growth, it gave notice that it had several targets for it violence. One was African Americans. A second were the “Carpetbaggers,” white civilians who came from the North to either help establish Reconstruction or make capitalist investment in the South. The third were the “Scalawags.” Blacks could be put back into the chains that had held them under slavery. Carpetbaggers could be driving back North. But, Scalawags were native to the South, they were indistinguishable from other white Southerners, Many were small farmers or merchants, and they had family connections with the broader Southern white community.

As Scalawags became targets of the Klan in 1868, the pro-Klan newspaper the Edgefield Advertiser from Edgefield South Carolina published an explanation of who the Scalawags were. It quotes Webster’s Dictionary which says that the American definition is of a “low, worthless fellow…” It then quotes the Petersburg Express from Virginia which said that “We venture to assert that no word in our language can so thoroughly delineate the native Southron, who, when his race is threatened with serfdom to his former slaves, baselessly herds with the enemy-in secret leagues gives ‘aid and comfort’-and for the sake of paltry gain barters honor, and lives upon the sickening odors of negro love.”

While the Edgefield Advertiser and the Petersburg Express were sympathetic to the Klan, Other voices weighed in on the danger posed by Scalawags.

Robert Toombs was an important political and military leader of the Confederacy. A pre-war Whig, he became a Democrat. Here is a report on a speech he gave in support of the 1868 presidential candidacy of Horatio Seymour at a “Ratification Meeting.” These were mass meetings at which local party members “ratified” the nominee of the national parties: Toombs said that the Scalawags were “native whites whose vileness and love of plunder have made them desert their State and race.” He said that every honest man should take up the whip to “lash the rascals naked.” A common punishment for slaves was not to be employed against Southern white “Scalawags.”

The same sentiment is echoed in Louisiana. The New Orleans Crescent on Nov. 22, 1868 said that a Scalawag was more despised than a Carpetbagger. A Scalawag is “simply a fellow who, having been a Confederate during the war…deserted to the enemy and became a Radical…”

The Klan and other white terrorist groups saw the so-called “Scalawags” as a principal enemy in the fight for the Southern future. For example, when the governor of Arkansas created a loyal militia in 1868, three-quarters of the 800 men were Southern whites and only one-quarter were Blacks. Grant’s aide Horace Porter reported back to Washington that nineteen of the “assassins” of the Klan and other groups had been captured by this militia and its allies among the “Scalawag” and Black communities. Porter said that as Federal troops were drawn down, those who were threats to the government in the Ku Klux believed they could quickly take control of Arkansas but that the alliance of Blacks and “Scalawags” was a useful countermeasure to the violence planned by the “rebels.”

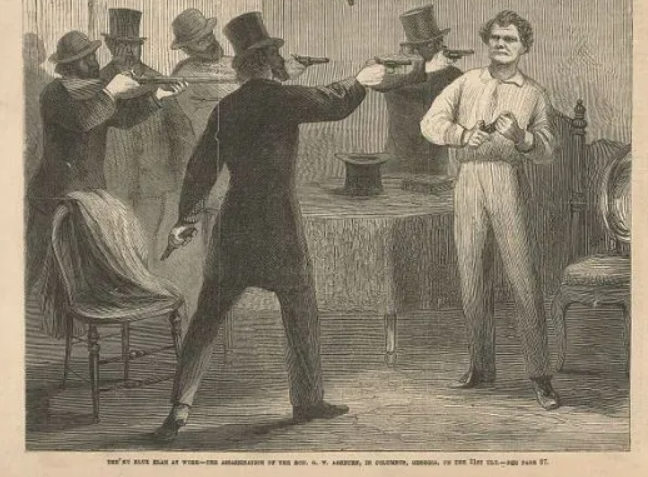

The “Scalawags” were identified by the Ku Klux Klan and sometimes targeted for death. George Ashburn was a Southern white man who joined the Union army during the Civil War. In 1867 he was a delegate to the Georgia Constitutional Convention where he helped draft provisions protecting the civil rights of African Americans. Ashburn decided to live among the African American community in Columbus, Georgia, and he was considering running for the United States Senate. On March 30, 1868 Ashburn participated in an integrated meeting of Republicans in Columbus. A few hours later, he was assassinated in his home by a group of five masked men.

Ashburn had been widely denounced by the Georgia Conservatives, a collection of men of various political stripes who united around opposition to African American suffrage. Newspapers reported that he had made many enemies among the Conservatives because of his advocacy of civil rights. When Ashburn was murdered, local military authorities demanded that the killing be investigated by the civilian government. Captain Mills, the local military commander, reported to his commander, General George Gordon Meade, that the political structure in Columbus was unwilling to act against the assassins. Meade then removed the mayor, the board of aldermen, and the city marshal. Meade sent a detective to investigate the crime.

Detective H.C. Whitley reported that many witnesses had been intimidated into silence. After witnesses were removed to safe locations, nine men were indicted for the killing. A legal team, including the former Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens, defended the nine accused men. Eight witnesses testified against the the defendants. They included two who had accompanied the mob that had been at Ashburn’s home and others who had heard the men speak of the murder.

In the middle of the trial, Meade halted proceedings because military supervision of the state ended. The civil authorities never brought the accused men back to trial and they were welcomed home by a large crowd of white people when they were released from jail.

Sources:

Edgefield Advertiser Nov 04, 1868 Edgefield, SC Vol: 33 Page: 4

Edgefield Advertiser Sep 09, 1868 Edgefield, SC Vol: 33 Page: 4

The New Orleans Crescent Nov. 22, 1868 Page 4

The Ashburn Murder Case In Georgia Reconstruction, 1868 by Elizabeth Otto Daniell The Georgia Historical Quarterly Vol. 59, No. 3 (Fall, 1975), pp. 296-312

Report on the Ashburn Murder by George Gordon Meade 1868

New Georgia Encyclopedia Ku Klux Klan in the Reconstruction Era

Thank you for this article, I learned from it. Longstreet was labeled one, too.

Thanks Henry. Longstreet was the most prominent “Scalawag” after the war.

The five Civil Rights Cases of 1883, consolidated as United States v. Stanley, United States v. Ryan, United States v. Nichols, United States v. Singleton, and Robinson v. Memphis & Charleston Railroad, were a series of cases decided by the Supreme Court that ultimately led to the establishment of Jim Crow laws. These cases challenged the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which aimed to prohibit racial discrimination in public accommodations. In an 8-1 decision, the Court ruled that the Act was unconstitutional, effectively weakening federal protections for civil rights and allowing for the segregation and discrimination that became characteristic of the Jim Crow era.

Here’s a more detailed breakdown:

The Civil Rights Act of 1875:

This act aimed to protect the civil rights of African Americans by prohibiting discrimination in public accommodations, transportation, and other venues.

The Five Cases:

These cases involved African Americans who were denied service in hotels, theaters, and other public spaces, leading to lawsuits under the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

The Supreme Court Ruling:

The Court, in its 1883 decision, held that the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was unconstitutional because it attempted to regulate private businesses, which were not considered state actors and therefore not subject to constitutional protections.

very helpful and informative perspective on post war difficulties of reconstruction

Informative and revealing article.

From my studies, “What was going on in the South, after the Civil War?” was probably best expressed by General J.B. Gordon, first Commander of the UCV: “Now let us do our best in [the] peace, and win the victories on that field that we lost in the other.” [Reference “That Mystic Cloud” (2008) by Edward John Harcourt page 161.]

Excellent article Patrick Glad you are back! I hope other Civil War writers concentrate on this topic. It’s another brick in the Lost Cause philosophy that needs to come down and destroyed with accurate information. Well written and well done!!! Skip Collinge

So, a person who fights against his larger community (the Union), is a traitor – but a person who fights against his smaller community (his state or county), is a patriot? I guess do not see the connection to advocacy of the Lost Cause.

Tom

Irishconfederates, how many Confederates were tried for treason?

None.

Any white southerners that were ex union soldiers had no business going down south after the war. Pretty much asking for trouble.

When I was a kid I was told by my elders I deserved the trouble I got if I went into certain neighborhoods; they would have suggested the same to reconstruction era skalawags.