The Civil War at St. Elizabeths Asylum

ECW welcomes back guest author Madeline Feierstein.

When we think of medical care during the Civil War, mental health is often reserved for post-war conversations. Veterans who experienced “soldier’s heart” (an early term for PTSD coined by Dr. James Mendes Da Costa in 1867) were placed in Soldier’s Homes or admitted to insane asylums by distraught family members, sometimes decades after their military service had ended. The Civil War story of the Government Hospital for the Insane is often obscured by the history of wartime Washington, but this psychiatric center played an important role as a Union Army hospital on the outskirts of the nation’s capital.

Haga, Dan. Red Board: U.S. Government Insane Asylum. April 10, 2007. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/danhaga/456829905/in/photostream/.

Known today as St. Elizabeths Hospital, this 1855 structure followed the blueprint and treatment model popularized by Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride – the “Kirkbride Plan.” This building style allowed patients to wander through sprawling corridors, avoid overcrowding, and be treated for what were assumed to be moral and anti-social maladies. The Kirkbride Plan offered a respite from the dangerous and ineffectual habit of placing mental health patients into jails or almshouses. Until 1855, all asylums and sanatoriums were state-run. St. Elizabeths, the Government Hospital for the Insane, was the first federally-funded psychiatric hospital in the United States. Its launch and mission, however, would be interrupted by the onset of the Civil War in a highly guarded Washington, D.C.

Located in what is now termed Southeast D.C., Congress approved the construction of a government asylum in 1852. Newly inaugurated President Franklin Pierce commented in his 1853 State of the Union Address that the hospital’s completion “will prove an asylum indeed to this most helpless and afflicted class of sufferers, and stand as a noble monument of wisdom and mercy.”[1] Charles H. Nichols was named the first superintendent in 1852 while it was under construction and remained in this position for 25 years until 1877. Nominated by Dorothea Dix and personally selected by outgoing President Fillmore, he previously served a similar role at the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum in New York. Superintendent Nichols, while maintaining his executive position, volunteered as a surgeon in his own asylum’s General Army Hospital – a decision likely made after tending to the wounded at the battle of First Bull Run under the direction of General McDowell.

Ulke Bros. Portrait of Charles Henry Nichols (1820-1889). 1872. Smithsonian Institution Archives.

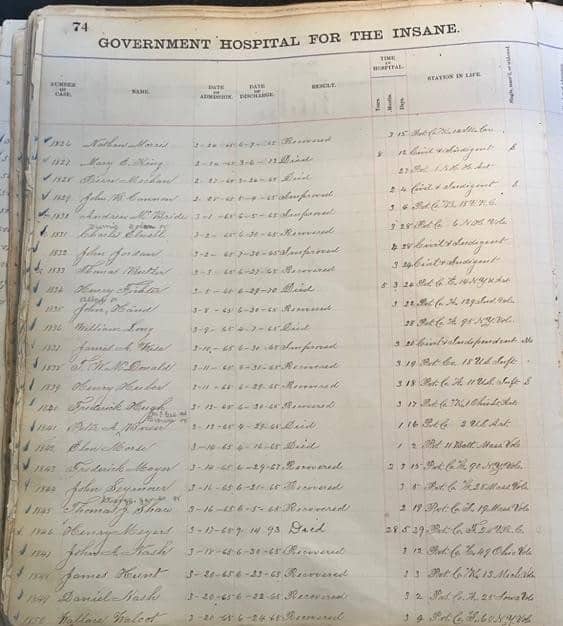

Admission entries for St. Elizabeths began in January 1855. Dr. Kirkbride’s original model allowed for roughly 250 patients to reside in the complex at any given time. Around 25-50 new patients were admitted each year through 1857; an estimated 100 new arrivals filled the halls in 1858, 1859, and 1860.

In summer 1861, the first military patients began arriving at the asylum. Most stayed a few weeks to a few months, and rarely over a year. Civilian patients were still admitted to St. Elizabeths during the Civil War; however, the Army and Navy personnel occupied more space than the Kirkbride Plan called for. Total new admission numbers for the wartime years, with an estimated 75-90 percent belonging to casualties, include: 1861 (114), 1862 (274), 1863 (397), 1864 (568), and 1865 (403).

The registers detailed reasons for admission related to the causes and strife of the Civil War, even before the bombardment at Fort Sumter. Diagnoses such as “war excitement” and “changes in life” later turned into “acute suicidal dementia,” “bursting of a cannon,” “prisoner of Belle Isle,” “hardships in prison,” and self-harming behaviors caused by “bullet wound of brain.” Several Confederate prisoners were transferred to St. Elizabeths from nearby prisons and hospitals in Alexandria or Washington for “acute mania.” The asylum also hosted a good number of political prisoners, noted as “prisoners of state” within the register.

Local newspapers advertised the asylum as a hospital in the early months of the war. One of the first mentions of soldier care at the site includes a rather high-profile account of Fire Zouave Col. Noah L. Farnham of the 11th NY Volunteers. He was admitted on July 29, 1861 for “derangement due to the wounds” received at the battle of First Bull Run.[2] From The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, we can gather that he suffered a “superficial wound near his left parietal lobe” (top-back of the head) and fell off his horse during the battle. Although the wound healed, “grave cerebral symptoms” appeared and led to hemiplegia (paralysis on one side of the body). He suffered from “concussion and irritation of the brain,” which led to a coma and his prompt death a few weeks later at the asylum on August 14.[3] This account likened his demise to being seriously weakened by disease. All this can lead us to believe that this wound to Farnham’s head was the cause of this so-called derangement. The asylum register categorized the colonel’s symptoms as a “chronic or acute mania.”

National Archives. “Admission Registers, 1855–1963.” Records of St. Elizabeths Hospital.

Sometime in fall 1862, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker was admitted to the hospital for wounds sustained at the battle of Antietam that September. President Lincoln visited several times to meet with injured and diseased soldiers, as well as Hooker. He is the highest-profile figure from the Civil War era to have been treated at St. Elizabeths.

Although adapted to treat and house military personnel, the asylum continued with Dr. Kirkbride’s prescribed treatment plans of fresh air and plenty of exercise for women, children, and men of a diverse population. Two detached lodges, the West in 1856 and the East in 1861, were designed exclusively for African-American patients.[4] They were otherwise segregated and not housed in the main complex, as far as the records show. Toward the end of 1864 and into 1865, patients from the United States Colored Troops were brought into St. Elizabeths, reflecting a shift in treatment for Black troops in the Capital region at this time. Efforts led by Head Surgeon Dr. Edwin Bentley in Alexandria pushed for more inclusive hospital environments that gave equitable treatment to all Union soldiers.

Unlike military hospitals in the Department of Washington, there was no preference shown for officers of higher rank, although a majority of admissions were recorded as privates. Soldiers and sailors continued to be admitted for battle-related injuries and mental health struggles through the end of 1865. Many soldiers did not return to the front or even their hometowns, forced to remain confined to the asylum well into the 1890s and the turn of the 20th century.

The Civil War Cemetery, formally known as the West Campus Cemetery, is located near where the main center building stands today. In 1873, the West Campus grounds were overcrowded and grew to 600 graves. The solution was to establish an East Campus Cemetery that now holds an additional 5,000 burials, many from succeeding American wars.

From Reconstruction through the early 1900s, St. Elizabeths expanded its campus and added a magnitude of outbuildings and amenities. Coupled with the surge of experimental treatment for the mentally ill, St. Elizabeths continued to follow the Kirkbride tradition and provide ample space, open air, and activities for its patients to take part in. One of the most significant buildings to be constructed was the Allison C (Building 24), due to its association with the care of Civil War and military veterans of later wars, including the Spanish-American and First World Wars. Constructed in 1899, it diverged from the original Kirkbride plan and represented the shift toward small free-standing cottages. Allison C combined with Allison A, D, and B to house an aging population of white, male Civil War veterans.

The Government Hospital for the Insane is no longer in operation. After a trend of decline, the complex transferred all patients to a newer, modern St. Elizabeths Hospital by 2002. The current site is now the headquarters of the Department of Homeland Security.

Madeline Feierstein is an Alexandria, VA historian specializing in psychiatric institutions, military hospitals, and prisons. A native of Washington, D.C., her work has been showcased across the Capital Region. Madeline leads efforts to document the sick, injured, and imprisoned soldiers that passed through Civil War Alexandria. Additionally, she interprets the burials in Alexandria’s historically rich cemeteries with Gravestone Stories. Madeline holds a Bachelor of Science in Criminology from George Mason University and a Master’s in American History from Southern New Hampshire University. Explore her research at www.madelinefeierstein.com.

Endnotes:

[1] Pierce, Franklin. “Franklin Pierce: First Annual Message.” Edited by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley. The American Presidency Project, December 5, 1853. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/first-annual-message-8.

[2] The National Republican. (Washington, D.C.). 29 July 1861. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014760/1861-07-29/ed-1/seq-3/.

[3] Barnes, Joseph K. Surgeon General. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. (1861–65). Part 1, Volume 2. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1870, 109-110. Civil War Washington. https://civilwardc.org/texts/cases/med.d1e7142.html.

[4] National Archives. “Lodge for Colored Patients.” Records of St. Elizabeths Hospital. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/84786250.

Staunton, Virginia had a large insane asylum that was in use more than 100 years after the Civil War, until it was finally closed in the late 1960s. Does anyone know if Confederate soldiers suffering from psychiatric trauma were treated there during the war?

Very informative; thanks