One Final Newspaper Roll Call

Casualties during the Civil War were extreme. In some battles one-third or more of participating combatants became casualties. Hearing anecdotes about units suffering fifty percent casualties is not atypical. Thanks to the nature of our free press, the Civil War media frequently printed such information. Often accompanying reports from the front were corresponding lists of casualties, which all too often found their way in newspapers. Indeed, many movies about the Civil War feature this to visually demonstrate the conflict’s cost in lives. Even after major Confederate armies surrendered and soldiers returned home, this continued, and in July 1865 another round of names was printed in newspapers across the United States.

As the war wound down, the task of battling armies shifted to one of preparing soldiers to return home. This included emptying enemy prisoner of war camps and hospitals. Unfortunately, that also meant learning that many soldiers in these camps and hospitals had instead died during the war (or in the case of Sultana’s boiler explosion, veterans being killed on their return trip). In July 1865, the names of U.S. soldiers who died during the war were printed in newspapers across the loyal states in what proved one of the final times during the Civil War such mass-printing of names was made.

The names ended up in newspapers across the nation, thanks to Henry C. Houghton of the U.S. Christian Commission. As Houghton explained, as the war in Virginia ended, his associates “passed over the grounds along our lines before Petersburg and Richmond” where they recorded “inscriptions from the head-boards that had been put up by comrades.”[1] Also included were prisoners of war who died either at the prison or hospital in Danville, Virginia, as well as at City Point.

As newspapers received the listing of names, they began printing them, in the hope of providing final comforts to families at home who likely did not know whether their loved ones were coming home or not. I have managed to find the newspaper printings of these deceased veterans from Maine, Ohio, Missouri, Illinois, Kansas, Vermont, and Pennsylvania.[2] Most of these entries include multi-column printings in the newspapers, but the most somber of entries is that of names printed by the Philadelphia Inquirer. It took two days and three pages to list all Pennsylvania’s dead, including an entire page completely dedicated to the effort.

This is a great reminder that even though the war was winding down by July 1865, there were thousands of families still without information on their loved ones, fearing the worst and hoping for the best. Sadly, many families were likely crushed when they scanned the papers to see if their loved one’s name was there.

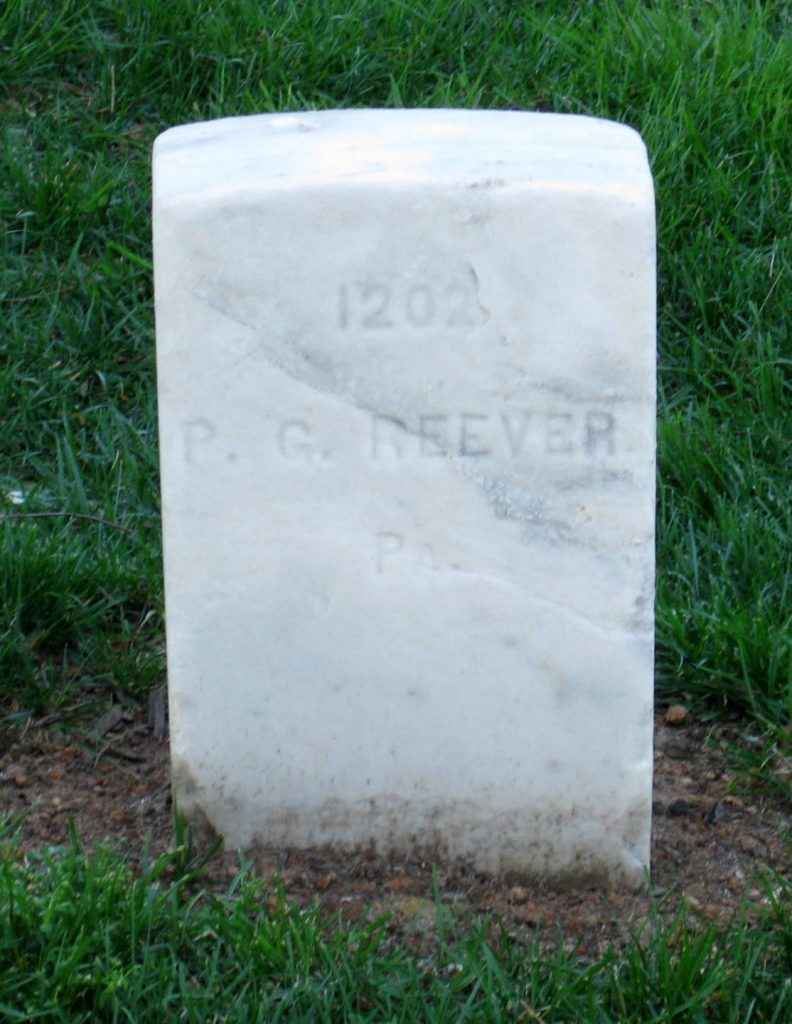

The cemetery housing soldiers on these lists who died at Danville was redesignated in December 1866, becoming the Danville National Cemetery. Many of the soldiers listed in these newspapers remain buried there.

Endnotes:

[1] “Out Illustrious Dead,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, July 19, 1865.

[2] “The Graves of Our Heroes,” Portland Daily Express, Portland ME, July 21, 1865, Page 2; “Union Soldiers Buried in Virginia,” The Weekly Perrysburg Journal, Perrysburg, OH, July 25, 1865, Page 3; “Union Prisoners Who Died at Danville,” Daily Missouri Democrat, St. Louis, MO, July 24, 1865, Page 4; “Graves of Vermont Soldiers,” Vermont Journal, Windsor, VT, July 29, 1865, Page 5; “Out Illustrious Dead,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, July 19, 1865, Page 8; “Out Illustrious Dead,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, July 20, 1865, Page 2-3;

An excellent and informative post. Thanks.