The Richmond Resistance: Elizabeth Van Lew’s Enterprise

ECW welcomes back guest author Stephen Romaine.

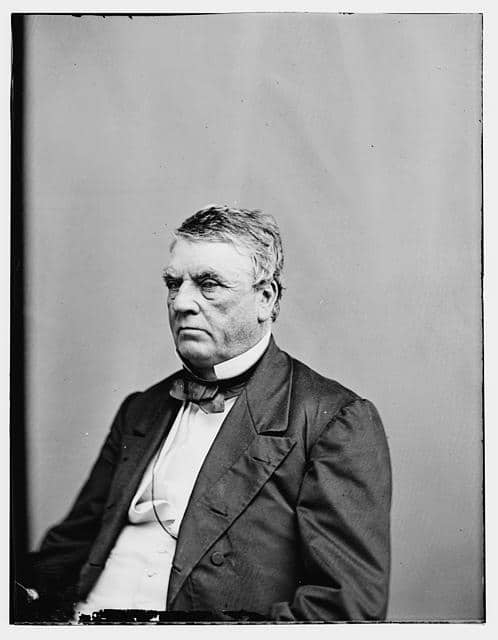

Before daybreak, March 2, 1862, one day after a declaration of martial law effecting Richmond, John Minor Botts, a respected former U.S. congressman representing the Whig party in Virginia was hauled out of his home and imprisoned. Charges were not specified, but “treacherous correspondence with the enemy” was suspected.[1] Also arrested was his close friend, Franklin Stearns, a successful Richmond businessman as well as approximately 150 disloyal citizens. Botts later suggested the intent was to “seal every man’s lips; all were afraid to express their opinions under the reign of terror and demands of despotism.”[2]

Yet a core group of individuals in the Richmond area with close ties to Botts and Stearns secretly banded together to engage in subversive activities against the Confederate establishment. In the early years of the war, the collaborators operated unnoticed by both the Confederates and the Union. Intelligence activities for the Federals were primarily dependent on embedded northern spies in the South, contracted detective services, army scouts, and the interrogation of rebel deserters.

It may very well have been the suspension of civil liberties leading to the arrest of close family friends that motivated Elizabeth Van Lew to escalate covert activities. In the past, the Van Lews hosted Whig Party social gatherings in their family home, a prominent mansion in the exclusive Church Hill section of Richmond. Both John Minor Botts and Franklin Stearns were frequent guests. Now in her mid-forties and living with her widowed mother, Elizabeth had become a respected member of Richmond society.

Elizabeth had previously received permission to visit Union officers in Libby Prison. She secretly accepted prisoner letters, sending them north to their families. “Letters like those passed on by Van Lew flowed north and south, through and around two armies, past a tightening naval blockade.”[3] She provided cash for prisoners to bribe guards and leveraged her Underground Railroad affiliations to help arrange safe passage across Confederate lines.

After the 1862 arrests, risk taking accelerated as Elizabeth built a spy network. William Rowley, an early recruit, was a Botts connection. He owned a farm outside of Richmond where he would shelter runaway slaves. Rowley became an indispensable member of Elizabeth’s team. He introduced Elizabeth to the Lohmann brothers, German immigrants who ran a grocery store. The Lohmanns used their wagons to hide Union prisoners, military deserters, and slaves, helping them escape north, avoiding Rebel picket lines. One of the brothers, F.W.E. Lohmann, was arrested near the end of the war and tortured. He refused to give up any of the other members of Elizabeth’s team.[4] The Richmond resistance also included clerks within government offices and numbers of slaves and former slaves operating as scouts, couriers and spies.

One of Elizabeth’s most daring Libby Prison feats was persuading prison officials to hire Erastus Ross as a clerk responsible for roll call. Ross was the nephew of Franklin Stearns. He would assume an angry disposition with prisoners to throw off suspicion from both his superiors and inmates while finding ways to help certain prisoners escape.

In February 1863, Union Col. George H. Sharpe was appointed head of the Bureau of Military Information. Recognizing the potential opportunity, Sharpe ordered his scouts to identify untapped potential Union assets in Virginia. “The locally recruited civilians were often transplanted northerners, British immigrants, former noncommissioned officers of the old regular army, and a strong native Unionist element which had profoundly disagreed with Virginia’s secession.”[5] Van Lew’s close friend John Minor Botts was most likely high on the list.

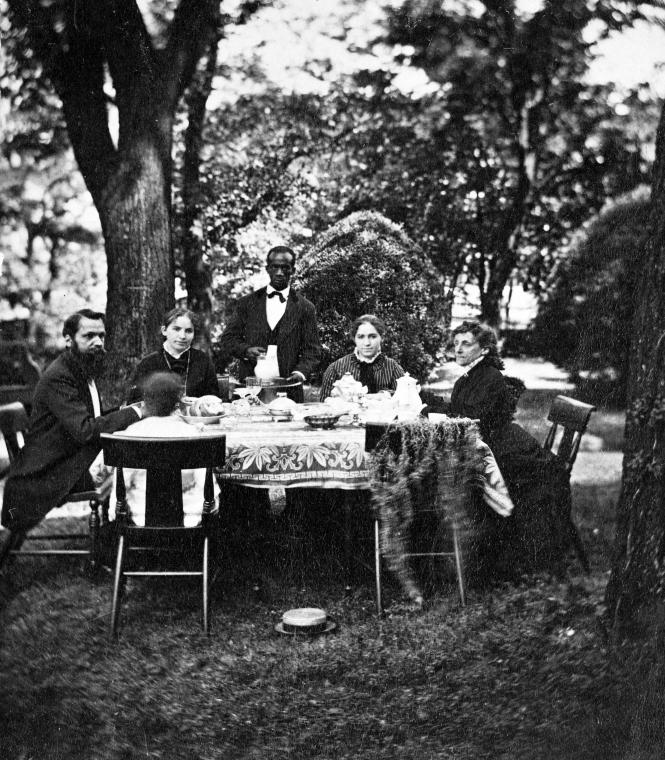

Botts spent eight weeks in solitary confinement and four additional months under house arrest. In January 1863 Botts took up residence on land he acquired in Culpeper County. Armies from both the North and South passed through his estate, and he met with generals from both sides.[6] In late 1863, five months following Yankee victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Botts hosted dinner for Union major generals at his new plantation home. As suggested the next day in The New York Times, “This probably will give fresh cause of offense to the Richmond junta.”[7]

Sharpe may have had a hand in making a connection between Samuel Ruth, already working with the Union, and Elizabeth Van Lew. During the 1862 Peninsula campaign Ruth, superintendent for the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac Railroad, slowed down trains and caused at least one derailment during the Seven Days Battles. With the rebels fortifying defensive positions, smuggling escaped soldiers and runaways presented increased risk. Ruth’s team would now provide transport to the Potomac. “The Van Lew group produced most of the information, and Ruth’s agents were now its principal conveyors to the army.”[8]

At some point in 1863, Elizabeth Van Lew placed an agent named Mary Bowser in the Confederate White House in the role of a slave housemaid.[9] Mary became her most valuable agent. Born a slave to the Van Lew family, Mary was taught to read and write against Virginia law and was secretly freed with the rest of the Van Lew slaves when Van Lew’s father passed away. In late 1863 Elizabeth established a direct channel of communication with Union Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler. She passed invisible ink messages via James River “Flag of Truce” boats used for prisoner exchanges.

After the war, Van Lew destroyed all documents related to clandestine activities to protect her agents and herself. What specific intel Mary was able to pass on is not verifiable. However, Jefferson Davis often worked from home and when possible liked to give in-person orders to his generals. Davis also did this with Captain Thomas H. Hines, the leader selected to execute ground operations designed to provoke insurrection across the North. In May 1864 highly confidential orders were given to proceed. The Lincoln Administration received forewarning four days after the Davis meeting, passed on from Butler. Early Union counterinsurgency efforts were put in place that helped neutralize the threat.

Upon establishing his headquarters in City Point, Virginia, Col. Sharpe indicated that Grant received encrypted communications on average three times a week from Elizabeth Van Lew.[10] Richmond message carriers, most often slaves and former slaves, used a network of underground safe stations before crossing enemy lines, evading rebel sentry locations at great personal risk.

The Richmond resistance evolved into a highly effective spy ring during the Civil War. The best indication of the impact of Van Lew’s Richmond resistance comes from the post-war endorsements of Van Lew and her operatives:

Ulysses S. Grant meeting with Elizabeth Van Lew: “You have sent me the most valuable information received from Richmond during the war.”[11]

General Sharpe, Bureau of Military Information: “John Minor Botts wrote from prison for her advice and protection and Franklin Stearns took her orders… They (the Van Lews) sent emissaries to our lines; when no one else could for the moment be found, they sent their own servants. They employed counsel for union people on trial—they had clerks in the rebel war and navy departments in their confidences; and soon after our arrival at City Point, Miss Van Lew mastered a system of correspondence in cipher by which specific information asked for by the General was obtained.”[12]

Colonel D.B. Parker, Grant’s City Point staff: “Miss Van Lew had a friend—a trusty Union man—who was a clerk in the Adjutant-General’s Department at Richmond, where he had access to the returns showing the strength of the rebel regiments, brigades, divisions, and corps, their movements, and where they were stationed. From him invaluable information found its way to General Grant regularly through Miss Van Lew’s instrumentality. She also had a man in the Engineer Department, and he made beautifully-accurate plans of the rebel defenses around Richmond and Petersburg, which were promptly forwarded to General Grant.”[13]

Stephen Romaine is author of Secret Army Behind Enemy Lines and a contributing writer for At Home and in the Field published by the Society for Women and the Civil War.

Endnotes:

[1] “Martial Law Over Richmond. Arrest of Hon. John Minor Botts and Other Suspected Unionist” Richmond Enquirer (4 March 1862), 4.

[2] John Minor Botts, The Great Rebellion. (Miami: HardPress, 2017), Kindle Edition Location: 4329-4330.

[3] Ernest B. Furgurson, Ashes of Glory, Richmond at War (New York: Vintage Civil War Library, 1996), 95.

[4] Virginia Lohmann Nodhturft, F.W.E. Lohmann Elizabeth Van Lew’s Civil War Spy. (Parker: Outskirts Press, 2019), 151-153.

[5] Peter G. Tsouras, Major General George H. Sharpe and The Creation of American Military Intelligence in the Civil War, (Philadelphia: Casemate, 2018), 1600, Kindle Edition.

[6] Janet L. Coryell, “Union or Secession,” Library of Virginia, (Richmond: The Library of Virginia, 1998– ), 2:114–117

[7] “J.M. Botts Gives a Dinner” The New York Times, (25 November 1863), 4.

[8] Edwin C. Fishel, The Secret War for the Union: The Untold Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1996), 11096, Kindle Edition.

[9] Ryan, 11.

[10] Fishel, 11102, Kindle Edition.

[11] William Gilmore Beymer, Scouts and Spies of the Civil War, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 2003), 54.

[12] Ryan, 116-117.

[13] “The Richmond Spy,” Richmond Daily Dispatch, (17 July 1883), 1.

Considering how long it took Grant to take Richmond and Petersburg, the question becomes, was the information not that useful overall, or did the Union high command fail to adequately use that information?

Grant’s main objective was not the capture of Richmond and Petersburg, but to destroy Lee’s Army which was entrenched and determined to hold both cities to the bitter end. This led to grueling trench warfare and high causalities on both sides. The people who were in the best position to determine the effectiveness of information provided indicate it was hugely helpful… the head of Military Intelligence for the Union, General Sharpe, and Colonel Parker from Grant’s staff at City Point. Years later President Grant would make her Postmaster of Richmond. Unfortunately, Van Lew destroyed all her documents related to clandestine activities including those requested back from Washington. However, there are traces of intel provided in Gen. Butler’s correspondences consistent with type of intel received at City Point, as Parker indicated. One example was in response to a request for information prior to the Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid:

“…No attempt should be made with less than 30,000 cavalry, from 10,000 to 15,000 infantries to support them, amounting in all to 40,000 to 45,000 troops. Do not underrate their strength and desperation. Forces could probably be called into action in from 5 to 10 days 25,000, most [sic] artillery. Hoke’s and Kemper’s brigades gone to North Carolina; Pickett’s in or about Petersburg. Three regiments of cavalry disbanded by General Lee for want of horses. Morgan is applying for 1,000 choice men for a raid.”

Despite pleas from Butler, the troop numbers recommended by Van Lew’s team were substantially reduced, leading to dire consequences.

Terrific essay!

As usual, Stephen Romaine has unearthed wonderful research to support the new points of information he has provided about Elizabeth Van Lew and her invaluable network. Given Van Lew was a successful spy who destroyed all her papers, Romaine has been able to find wonderful supporting evidence to illuminate the work she did for the Union.