Combatting Crime in Union-Occupied Alexandria

ECW Welcomes back guest author Madeline Feierstein.

Overnight, the port city of Alexandria, Virginia transformed from a Southern boom town into a Northern military base. Transient soldiers replaced businessmen on bustling Washington Street. Uniformed officers occupied private residences and former shops, left deserted by their previous owners’ flight into the Confederacy. Like several other occupied towns in the South, Alexandria was reduced to lawlessness and high rates of violence without initial strict regulations. In the midst of all this, thousands of citizens, military personnel, formerly enslaved people, and politicians vied for normalcy in very abnormal times.

On May 24, 1861, Union troops began a federal occupation of Alexandria upon Virginia’s ratification of its ordinance of secession the day prior. At the head of this operation was a military government with one mission in mind: to protect Washington, D.C. from Confederate invasion and subversion. The government disbanded the civil authorities and shuffled through several military governors in the first year.

During this time, soldier and citizen crimes skyrocketed. Debauchery and disorder were no longer confined to underground scenes or behind closed doors, giving this city with colonial charm a rather disrespectful reputation. Soldiers who had not yet been sent out to the front – who remained bored or diseased through contagion – found themselves far from home in an unfamiliar land. Citizens who sided with the Union either rejected this “Yankee invasion” or grew to resent the transformation of their town.

Reports of thievery and banditry were commonly reported in the Alexandria Gazette. “Thieves are about again,” warned a July 1864 column, “Other depredations were committed. Look out!”[1] An October 1862 notice detailed that local Benjamin Waters’ residence was robbed by a soldier and “chase was given the thief but he escaped.”[2]

Vulnerable populations of self-emancipating refugees escaping bondage did not have a protection force to turn to. Often, it was through the kindness of benevolent societies and decency of private individuals that they received medical care, proper housing, and advocacy at the start of the occupation. Something needed to be done about the violence, filth, and mismanagement occurring in Alexandria’s streets.

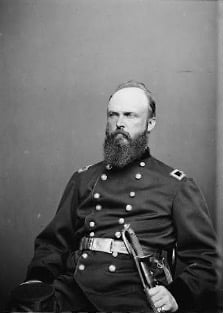

In August 1862, Brig. Gen. John Potts Slough was appointed as the newest military governor. Juxtaposing his weaker predecessor, Brig. Gen. William Montgomery, Slough governed the garrisoned city with an iron fist. Montgomery had teetered between regulating the city and appeasing locals; the role of a military governor within the first year of the war was uncharted territory. Unfortunately, his ambivalence made him an unpopular figure, resulting in his resignation before the first anniversary of Union control.

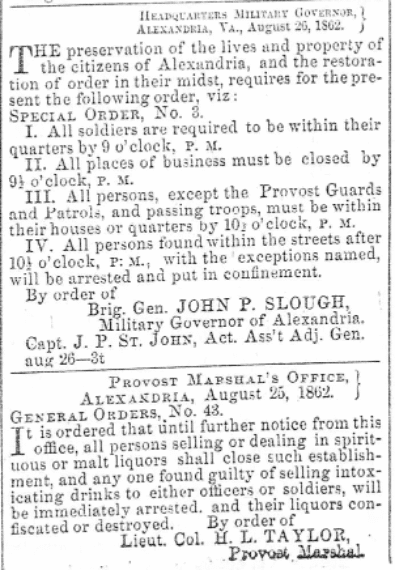

Immediately upon taking office, Governor Slough coordinated a rather assertive litany of policies to combat the obstacles to Alexandria’s operations. Curfews for both military personnel and citizens were enacted in August 1862, forcing any Alexandrian “night life” to close by 10 o’clock. Acting Provost Marshal H.L. Taylor enacted an early form of prohibition by banning the sale of liquors to military of any rank, announced alongside the new curfew laws. A few days later, Slough also used the Gazette to state that “the discharging of firearms within the city limits was strictly prohibited.”[3] Additionally, he issued General Orders No. 2 on September 16, 1862, which called for the immediate abolition of crimes against contrabands (the term for formerly-enslaved people entering Union territory):

“Information having been received at these Headquarters, that certain citizens and soldiers of low repute are constantly committing depredations upon the property and persons of defenceless inhabitants [Contrabands], who have by force of circumstances been compelled to resort to Alexandria as a place of shelter and protection – therefore, notice is hereby given that all persons detected participating in such lawless acts, will be arrested and placed in confinement.”[4]

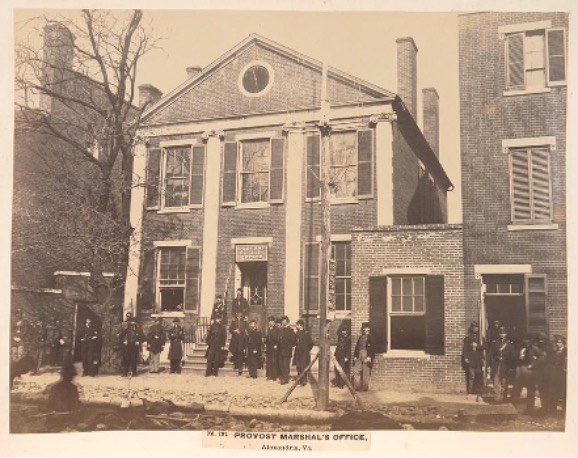

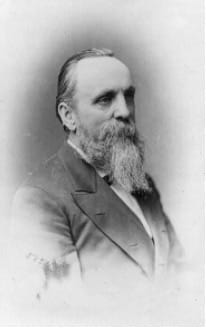

The following spring, Lt. Col. Henry Horatio Wells took the position of provost marshal in 1863, overseeing law enforcement and courts until the end of the war.[5] A Michigan abolitionist, politician, and lawyer who fought for alcohol temperance, Provost Marshal Wells bolstered the jurisdiction of this office, increasing not only its reach but also its ability to combat crime. By adding oversight of the court system, Wells placed himself at the start and finish of the adjudication process against Alexandria’s crime problem. A military police force was established, and additional prisons were opened within the city. He mandated a more meticulous recording of all crimes, sending soldiers to the Provost Marshal’s Office for a myriad of situations: determining sentences, deserters, prisoners-of-war, passes in and out of Washington, and the enforcement of martial law.[6]

The crime rate in occupied Alexandria could not be solved with layers of new rules and restrictions, but the threat of imprisonment or reassignment served well in this kind of environment. Due to Slough and Wells’s diligence and commitment to the law, Alexandria was spared from tragic vulnerability that might have left it open to collapse or Confederate invasion. This would not be without consequence, however, since thousands of Union soldiers – and even citizens – were locked in the city’s subpar prisons, subject to disease, additional violence, and malnutrition. Some argue that these laws hurt civilians more than protected them, stripping them of civil rights in the name of national security. Alexandria, however, remained intact and fortified during this conflict – and that was the military government’s main concern.

Madeline Feierstein is an Alexandria, VA historian specializing in psychiatric institutions, hospitals, and prisons. A native of Washington, D.C., her work has been showcased across the Capital Region. Madeline leads efforts to document the sick, injured, and imprisoned soldiers that passed through Civil War Alexandria. Additionally, she interprets the burials in Alexandria’s historically rich cemeteries with Gravestone Stories. Madeline holds a Bachelor of Science in Criminology from George Mason University and a Master’s in American History from Southern New Hampshire University. Explore her research at www.madelinefeierstein.com.

Endnotes:

[1] Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, VA), July 15, 1864.

[2] Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, VA), Oct. 18,1862.

[3] Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, VA), Aug. 28,1862.

[4] Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, VA), Sep. 18,1862.

[5] Wells was promoted to Brigadier General by June 3, 1865.

[6] Russell, Andrew J. “Provost Marshall’s Office, Alexandria, Virginia.” c.1863. Chrysler Museum of Art. https://chrysler.emuseum.com/objects/33105/provost-marshalls-office-alexandria-virginia.

This series of stories on Civil War-era Alexandria is very interesting. Hope there are more to come. Perhaps addressing CSA spies in town?

Thank you so much! I love being able to shed more light on Alexandria’s role and experience. CSA spies is definitely among the upcoming articles 🙂