“He was the soul of honour”: A Kansas Editor’s Experience of War

ECW welcomes back guest author Devan Sommerville.

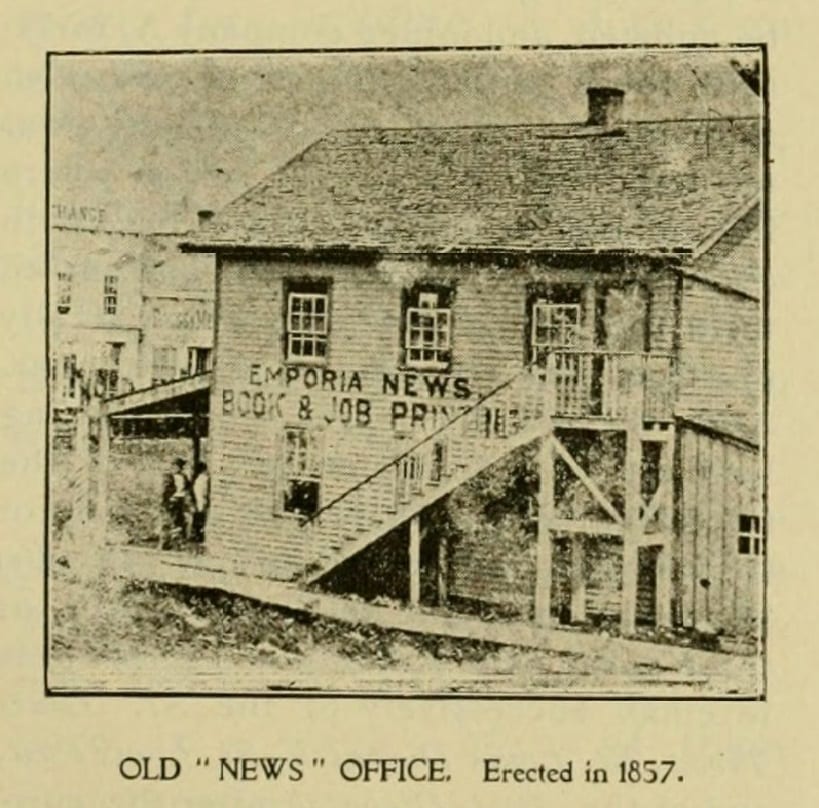

The Emporia News was a busy enterprise. The weekly publication was the newspaper of record in the young, burgeoning Kansas town. Its crowded pages reflected the interests of its readership: local matters, proceedings of the state legislature in Topeka, news delivered by telegraph, agricultural advice, and political commentary.

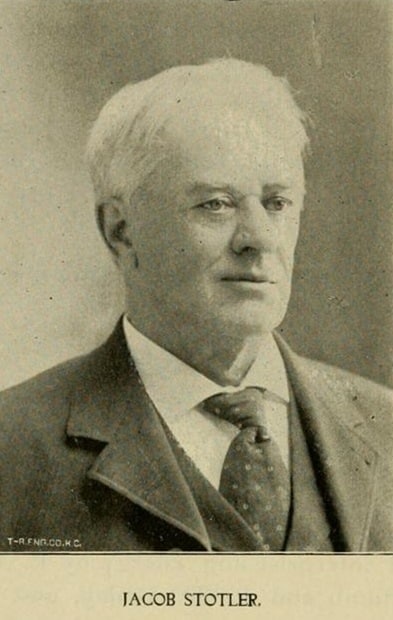

Subscribers paid two dollars annually – in advance – and expected a timely edition. Appreciating this, editor Jacob Stotler took to the June 8, 1861 edition of his paper to explain why none was printed for the previous two weeks. “We hate apologies, and shall make none,” the editor pronounced, explaining that the first delay was caused by a relatable frontier reality: an overdue paper order.

The second delay was more significant: “we were short of hands.” Continuing, the editor explained that, “Our foreman, Charles Stotler, went off with the Emporia Guards, to Lawrence, to handle a different kind of a ‘shooting-stick’…and we were left in the lurch.” Left unstated, but certainly understood by most subscribers, was that Stotler’s brother was off to war.[1]

Frances Milton Trollope, the English traveloguer, observed of the antebellum United States that “throughout all ranks of society, from the successful merchant…to the domestic serving man…are all too actively employed to read, except at such broken moments as may suffice for a peep at a newspaper.”[2]

A local newspaper was an essential mark of progress on the frontier. This was particularly so in Emporia, founded in the waning days of “Bleeding Kansas” by a pair of young newspaper editors, G.W. Brown and Preston Plumb, alongside militant “free soil” politician George Deitzler.[3] Jacob Stotler, a fellow newspaperman and compatriot of Plumb’s from Ohio, took up the effort. The editorial perspective of his Emporia News mirrored that of the town’s founders: staunchly Republican and anti-slavery.

Frontier newspaper editors lived a hard life. With hard currency in short supply, subscriptions were often paid in kind. As winter approached, Stotler solicited subscribers for food and reminded them that “those intending to bring wood to pay for their papers, will confer a favour by delivering it before the bad weather sets in.”[4]

Deeply held convictions drove Stotler to persevere through this hardship. His decision to settle in Kansas was motivated by support for the “free soil” cause and a determination to prevent the extension of slavery. He saw the end of slavery as a moral cause. Responding to the Emancipation Proclamation, Stotler declared to his readers that “It ought to have been done sooner, but better late than never…Verily, the world progresses. The death-knell of slavery is sounded.”[5]

While maintaining editorial detachment, Stotler’s writings display pride in his brother Charles being among the first in Emporia to enlist. “Whenever any of our hands wish to go off and enlist in the cause of the Government, we shall give them a patriotic slap on the shoulder and tell them to go, paper or no paper.”[6]

Stotler’s patriotic zeal was a community affliction. Forty-five men from Emporia – Charles Stotler among them – were organized under the captaincy of William F. Cloud. Following a two-day wagon journey and gaining recruits along the way, the Emporia Guards were mustered in as Company H of the 2nd Kansas Infantry Regiment, a three-months’ unit.[7] Prior to their departure, the men were feted by the citizens of the town and presented with a flag sewn by local women, with Jacob Stotler noting that they “will not soon forget the fair donors of their beautiful banner.”[8]

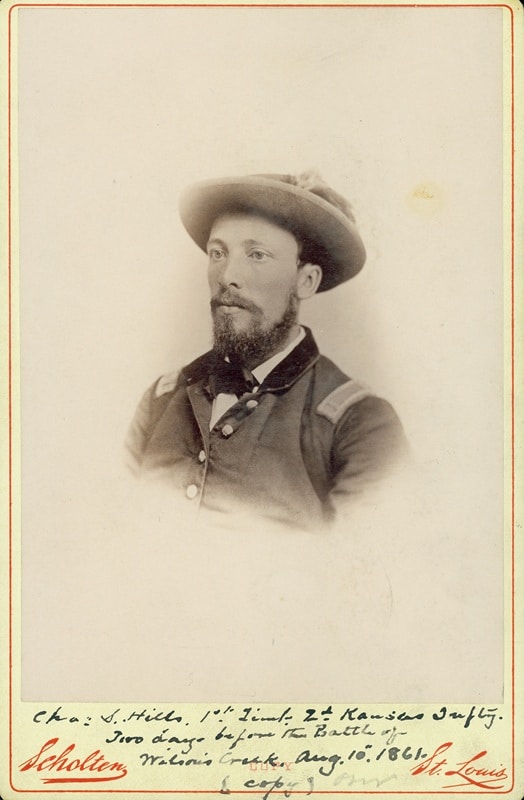

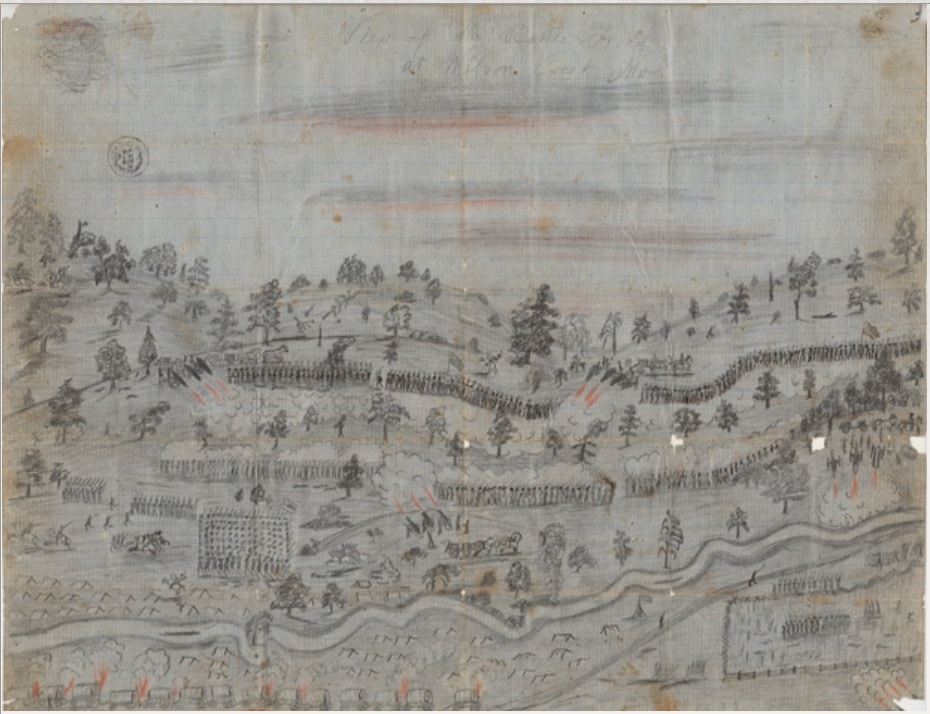

The grim cost of war would soon arrive. Within two months of their departure, the Emporia Guards and the rest of the 2nd Kansas were at the bloody Battle of Wilson’s Creek. Stotler rushed to deliver news of the battle and the role of the Emporia men. He enthusiastically printed an unsentimental letter from a local resident, Lt. Charles S. Hills, one of the officers of the company wounded in the battle. It vividly described the horrors of the battlefield and the suffering of the Emporia men. “It was a sickening sight to see the poor fellows calling for water, as they lay on the field, trampled under foot,” he recounted, “and the fearful carnage adding scores to their number each minute!”[9]

Noting that he believed the Emporia company had suffered more casualties than any other in the regiment, Hills provided a graphic inventory of those killed and wounded. Thomas Miller was “shot through the kidney – suffered beyond description”; Edward Trask received a “very severe” wound and “he suffered intense pain.” There were seventeen recorded casualties, including five killed, among the Emporia men at Wilson’s Creek.[10] Hills informed readers that the cost was higher: “All the boys received more or less scratches.” That included the prized flag, which was “completely riddled with shot and shell, and the brave one who carried it will not carry it home again.”[11]

Although Wilson’s Creek was a Union defeat, the battle was treated as a triumph in the pages of the Emporia News. The details of military strategy were unimportant; the Emporia men had bravely done their duty. “Our boys fought like devils for five long hours,” recalled Hills, who emphasized that the flag “has not been disgraced.”[12] Stotler celebrated his brother Charles and the heroes of Wilson’s Creek. He called upon the citizenry “to take measures to give them a public and hearty reception”, which occurred with great fanfare when the men returned to Emporia for discharge in October.[13] The company’s flag, “the old blood-stained, and bullet-riddled banner of Springfield,” was displayed outside of the Emporia House for all to see.[14]

Efforts were made to re-enlist the company for the duration of the war. Charles Stotler was not among them. Upon their return to Emporia, the now veteran soldiers shared that they “had suffered at times almost beyond description,” sucking moisture from green cornstalks while suffering from intense heat during the height of the Missouri summer.[15] These privations were a powerful disincentive, but when the Federal government called for 300,000 more volunteers the following summer, Charles enlisted again to serve in a new company, organized by his father’s close friend and future senator, Preston Plumb.[16]

In a few short months, grim tidings came to the Emporia News: Charles Stotler was seriously wounded at the battle of Prairie Grove. Plumb, in a republished letter, indicated that Charles was “shot in the back of the head – very dangerous” and recuperating in a hospital in Fayetteville, Arkansas.[17] For the next several weeks, Jacob Stotler reported updates on his brother’s well-being. While each expressed optimism for his recovery, increasingly aggressive treatment was apparent.

Before the end of the month, readers were confronted by a striking sight: a thick, black border wrapping around a lengthy obituary. Jacob Stotler shared “the most painful duty of our life”: Charles Stotler had died of his wounds. A separate column ran the following week, offering testimonials to his brother’s character from across the state. There had been no extensive memorials in the aftermath of Wilson’s Creek, a shared sacrifice for Emporia. But for the editor of the Emporia News, the price of war was now personal. Jacob Stotler made certain to equate his brother’s sacrifice alongside these revered community heroes: “He is numbered with Emporia’s heroic sons who fell at Wilson’s Creek – mourned by the whole community.”

The clearest emotion in Stotler’s words was anger. At the surgeons who he believed had neglected his brother’s care, that “such brutes could carry a little cold lead in their lazy brains a short time,” as well as “the hellish designs of scheming, usurping politicians, who, if they had their desserts, would be burning with the fire that is never quenched.”[18]

For Jacob Stotler, like millions of Americans on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line, it was a sorrow that would last for the rest of their lives.

Devan Sommerville is a consultant lobbyist based in his native Canada, living in Toronto, Ontario with his wife and young son. A lifelong student of the American Civil War and American Antebellum History, he holds an Honours Bachelor of Arts in History and a Master’s in Public Policy from the University of Toronto.

Endnotes:

[1] Emporia News. (Emporia, KS: June 8, 1861), 2.

[2] Frances Milton Trollope. Domestic Manners of the Americans, Volume I. (London: Whittaker, Treacher & Co., 1832), 88.

[3] Robert Triplett. “1857 – Emporia – 1957.” Emporia, Kansas Centennial Celebration June 30 – July 6, 1957. (Emporia, KS: Centennial Celebration Committee, 1957), 5-9.

[4] Emporia News. (Emporia, KS: November 9, 1861), 3.

[5] Emporia News. (Emporia, KS: January 10, 1863), 3.

[6] Emporia News. (Emporia, KS: June 8, 1861), 2.

[7] Jacob Stotler. Annals of Emporia and Lyon County (Emporia, KS: 1882), 43.

[8] Emporia News. (Emporia, KS: June 8, 1861), 3.

[9] C.S. Hills in Emporia News. (Emporia, KS: August 31, 1861), 2.

[10] Hills, 2; Stotler, 48.

[11] Hills, 2.

[12] Hills, 2.

[13] Emporia News. (Emporia, KS: September 7, 1861), 3.

[14] Emporia News. (Emporia, KS: October 12, 1861), 3.

[15] W.F. Cloud in Emporia News. (Emporia, KS: October 12, 1861), 3.

[16] Emporia News. (Emporia, KS: August 30, 1862), 3.

[17] Preston B. Plumb in Emporia News. (Emporia, KS: December 27, 1862), 2.

[18] Emporia News. (Emporia, KS: January 17, 1863), 3.

Kudos to Devan Sommerville for providing an excellent, informative article concerning rarely discussed aspects of the Civil War: Kansas troops and Wilson’s Creek. I do not believe I have ever seen a report on the involvement of Kansas in the Civil War, beyond Bleeding Kansas and the Fight against Missouri Border Ruffians. Well Done!

Mike Maxwell