Percy Wyndham: Foreign Volunteer of the Union

ECW welcomes back guest author Arie De Young.

In retellings of the American Revolutionary War, one of the most frequently highlighted parts is the crucial service of foreign volunteers as officers in the Continental Army. Whether the Marquis de Lafayette or Baron von Steuben, Tadeusz Kosciuszko or Johann de Kalb, they became one of the lasting legacies of the conflict.

The American Civil War produced its own set of foreign volunteers, albeit never reaching the same heights of rank and responsibility as their predecessors. Nevertheless, the story of how one of these men served the Union provides a fascinating look into the conflict.

Percy Wyndham was born September 22, 1833 on the ship Arab. The son of a distinguished British officer, he performed his first military service for France. He first took part in the 1848 Revolution as a student before joining the navy in July of that same year. This started his succession of switching allegiances.

In 1850, Wyndham resigned his naval commission and joined the British artillery in 1851. By October 1852, however, he resigned that post to take up one as a second lieutenant in the Austrian army. His exploits next led him to join Garibaldi’s Volunteers in Italy in 1860. Distinguished service with them brought him to brigade command and a knighthood by King Emanuel Victor. As the Expedition of the Thousand began to wind down, he was in need of a new adventure. With the American Civil War breaking out an ocean away, Wyndham obtained leave to take part in that struggle.[1]

Wyndham found his opportunity on February 9, 1862, when Governor Charles S. Olden of New Jersey assigned him command of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry Regiment.[2] In spite of his extensive experience, his subordinates were initially far from impressed. One noted, “he seemed bent on killing as many horses as possible, not to mention the men,” and that he was “in search … [of] cheap renown.” An officer summarized him as “a big bag of wind.”[3]

Indeed, the colonel was to have a rather inauspicious start to his career. Taking part in the 1862 Shenandoah Valley Campaign, the Confederates captured Wyndham on June 6 outside of Harrisonburg. Exchanged several weeks later, he engaged in several skirmishes, including at Thoroughfare Gap.[4] This revived his reputation enough to be assigned command of the cavalry of the defenses of Washington. What followed was Wyndham engaging in a fierce, but fruitless pursuit of the “Gray Ghost of the Confederacy,” John S. Mosby.[5]

A bitter rivalry developed between the pair. Mosby’s ability to raid Union forces and escape the traps set for him continually vexed Wyndham. As Mosby sneered in a letter to J.E.B. Stuart, “he set a very nice trap a few days ago to capture me in. I went into it, but contrary to the Colonel’s expectations, brought the trap off with me.”[6]

Exasperated, Wyndham sent “many insulting messages”[7] and even threatened to burn the town of Middleburg and the neighboring region on January 28, 1863.[8] To put a final emphasis on the one-sided nature of their relationship, Mosby nearly succeeded in making Wyndham a prisoner a second time on March 9.[9]

Wyndham returned to command of his old regiment that same month, but ill fortune continued to follow him. Having only been back for several weeks, his superior Maj. Gen. George Stoneman placed him under arrest for failing to accompany his command on picket duty. Although released shortly thereafter, it was yet another debacle for what had been a rather undistinguished tenure in Union command.[10]

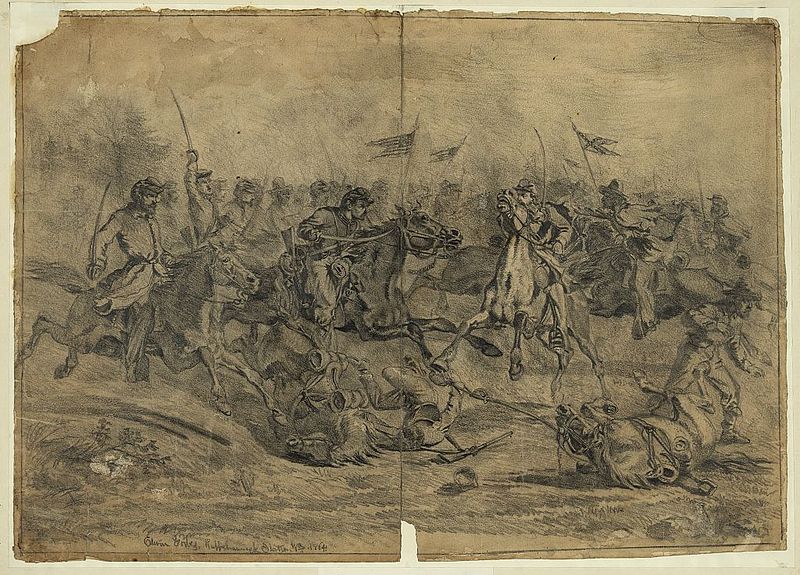

After all of this strife, he finally had his moment in the sun. During Stoneman’s Raid, Wyndham’s command left a destructive swath in their wake without the loss of a single casualty.[11] The battle of Brandy Station further burnished his name. Now commanding a brigade, he slowed the advance of the whole division over fears of an unmanned Confederate cannon atop Fleetwood Heights.[12]

Once in combat, however, Wyndham proved his valor. He led a charge that captured the headquarters of J.E.B. Stuart. Furthermore, his regiment fought fiercely to hold the heights they captured, only withdrawing under immense pressure. Towards the close of the fight, Wyndham suffered a serious wound to his leg that removed him from command. Even in their escape, the 1st New Jersey brought 150 prisoners off the field.[13]

In his after-battle report, Wyndham’s division commander, Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg, recorded, “I would, however, mention Col. P. Wyndham, First New Jersey Cavalry, commanding Second Brigade, and Col. J. Kilpatrick, Second New York, commanding First Brigade, who gallantly led their brigades to the charge, and throughout the entire engagement handled them with consummate skill. Colonel Wyndham, although wounded, remained on the field, and covered with a portion of his command the withdrawal of the division.”[14]

Even in his moment of greatest triumph during the war, however, trouble did not long elude Wyndham. Sent to Washington D.C. to recuperate from his injury, he was assigned to gather available cavalry units in the city to counter any potential threats by Stuart. Going beyond this, he formed his own cavalry depot to remount and refit horsemen named Camp Wyndham.

All throughout, his injury continued to plague him. In spite of this, Wyndham was ordered to return to his regiment in late July and hand over control of the camp. He pleaded against this order to no avail. When his leave concluded, Wyndham still had not returned to the 1st New Jersey. His commanding officer, Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasanton, labeled him as “away from his command without authority.”[15]

By October 2, Wyndham was formally charged as being “absent without leave” by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. By the time this order reached the Army of the Potomac’s headquarters, Wyndham had finally returned to his command, leaving the army’s commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade in a bind. Upon his request for further instructions, a request came from Wyndham to be relieved from active military duty and sent to Washington. Almost a year later, in June 1864, Wyndham tried once more to return to active service in the Army of the Potomac. Without permission to be there, he was arrested, returned to Washington, and mustered out of the army, thus ending his career in the American Civil War.[16]

The now former colonel moved to New York City and operated a military school there. He ran the program for two years before the outbreak of the Austro-Prussian War sent him hurrying back to Europe to rejoin the Italian Army. After brief service in a brief war, Wyndham returned to America to run a petroleum refining company. When this business went under due to the explosion of one of his stills, he fled to Calcutta and once more remade himself as the editor of a comic paper entitled The Indian Charivari.[17]

Poor financial decisions drove him to flight, this time to Burma. It was there that the flamboyant officer finally met his end. During the first demonstration of a hot air balloon Wyndham constructed in the city of Rangoon, he ascended 500 feet into the air before his vessel burst into flames. His audience could only watch in horror as it plummeted into a nearby lake. Wyndham’s body was recovered, and it was deemed that he most likely died of asphyxiation before even hitting the water.[18] Thus ended the life of an ever-active soldier of fortune.

————

Arie De Young has long been fascinated with the American Civil War, whether it is exploring battlefields, reading books, or attending roundtables. Currently attending Anderson University to achieve his bachelor’s degree, he plans to enter a doctorate program and academia. He has twice been a featured speaker at local Civil War roundtable events.

Endnotes:

[1] Samuel Toombs, New Jersey Troops in the Gettysburg Campaign From June 5 to July 31, 1863 (Orange: The Evening Mail Publishing House, 1888), 402-403.

[2] Toombs, New Jersey Troops in the Gettysburg Campaign, 402-403.

[3] Eric J. Wittenberg, The Union Cavalry Comes of Age: Hartwood Church to Brandy Station, 1863 (Washington D.C.: The History Press, 2017), 24.

[4] Toombs, New Jersey Troops in the Gettysburg Campaign From June 5 to July 31, 1863, 403-404.

[5] Edward G. Longacre, Lincoln’s Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of the Potomac (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 2000), 133.

[6] James J. Williamson, Mosby’s Rangers, (1896; reis., Time-Life Books Inc, 1981), 401

[7] Williamson, Mosby’s Rangers, 36.

[8] Jeffry D. Wert, Mosby’s Rangers: The True Adventures of the Most Famous Command of the Civil War, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990), 41.

[9] Wert, Mosby’s Rangers, 45.

[10] Robert F. O’Neill, Chasing Jeb Stuart and John Mosby: The Union Cavalry in Northern Virginia (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2012), 256.

[11] Wittenberg, The Union Cavalry Comes of Age, 216-217.

[12] Longacre, Lincoln’s Cavalrymen, 159.

[13] Wittenberg, The Union Cavalry Comes of Age, 282-285.

[14] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, vol. 27, part 1, 951.

[15] O’Neill, Chasing Jeb Stuart and John Mosby, 256.

[16] O’Neill, Chasing Jeb Stuart and John Mosby, 257.

[17] Toombs, New Jersey Troops in the Gettysburg Campaign, 404.

[18] Frank Jastrzembski, “You Know Him for His Facial Hair. But You Might Not Know the Tale of His Tragic Death.” America’s Civil War, January 30, 2023. https://www.historynet.com/percy-wyndham-death/.

I have always been fascinated with his story. Love the facial hair too, wish I could grow something like that.

Enjoyable article.

Nicely done. Is there any book on Percy Wyndham you would recommend?

While there aren’t any books specifically about him to my knowledge, the two best books I would recommend are “New Jersey Troops in the Gettysburg Campaign From June 5 to July 31, 1863” by Samuel Toombs and “The Union Cavalry Comes of Age: Hartwood Church to Brandy Station, 1863” by Eric J. Wittenberg. The former is written by one of the soldiers who fought under Wyndham. It includes a nice biography detailing some of his life outside of the Civil War, albeit with a somewhat hagiographic lens. The latter provides great coverage of much of Wyndham’s Civil War service from the author who was the preeminent expert in Union cavalry.

Thank you.

Wyndham was one of several officers who passed word back to John Pope that Longstreet was passing through Thoroughfare Gap in the early moments of Second Manassas. As in the other cases, Pope didn’t believe him, to Pope’s detriment. As John Hennessy wrote in his masterful, “Return to Bull Run,” Pope based his strategy on what he wanted reality to be, not what actually was happening.