The Pirate Semmes: The Tightrope of Irregular Warfare

ECW welcomes back guest author Collin Hayward.

Raphael Semmes was born in Maryland in 1809 and entered the United States Navy in 1826 as a midshipman. He served much of his early career in the Caribbean conducting counter-piracy operations with the Navy’s West Indies Squadron.[1] Upon the outbreak of the war with Mexico, Lieutenant Semmes commanded the 10-gun brig USS Somers, which took an active role in the blockade of the Mexican port of Vera Cruz. Semmes quickly proved himself an aggressive young commander, but his early war record was plagued by misfortune. He captured and burned the Mexican blockade runner Criolla in a daring cutting out expedition, only to learn later that Criolla was a spy ship operating under the authority of the American Commodore David Connor. While pursuing another blockade runner, Somers capsized and sank in a sudden squall, resulting in the deaths or capture of more than quarter of the ship’s company.[2]

Despite this ignominious beginning to his war, Semmes was rescued and reassigned to USS Raritan as first lieutenant. Initially assigned to accompany landing forces into Vera Cruz, Semmes would accompany General Scott’s staff throughout the campaign. Semmes distinguished himself during the fighting around the San Cosme Gate during the battle of Chapultepec, where he emulated Lt. Ulysses Grant in directing the placing of artillery in elevated positions to support the storming of the gate by General Worth’s division.[3]

Semmes returned from Mexico as a military hero but remained ashore practicing law and supervising lighthouses until his resignation from the Navy in 1861 following Alabama’s secession and his acceptance of a Confederate naval commission.[4]

From the very outset, the Confederacy found itself at a significant disadvantage at sea. Starting in April 1861, a Union naval blockade began to constrict Southern ports. Lacking a navy of their own, the Confederacy sought an asymmetric approach to counter Northern naval supremacy. The Confederacy initially offered letters of marque to recruit privateers, but the ports of many foreign powers refused to receive them since the banning of privateering by the 1856 Treaty of Paris. The Union even went so far as to try the captured privateers of Savannah and the Jefferson Davis as pirates, before eventually agreeing to treat them as prisoners of war, thus granting the Confederate privateers the legal status as belligerents.[5]

The Confederacy eventually abandoned privateering but saw more success from blockade running and commerce raiding. Commerce raiding has a long history in warfare (where it was used extensively in the American Revolution, War of 1812, and the Napoleonic Wars) but remains contentious as it inherently pits state military force against civilian commerce. As such, while it meets the legal threshold to qualify as a traditional military activity, it inherently constitutes an example of asymmetric warfare.

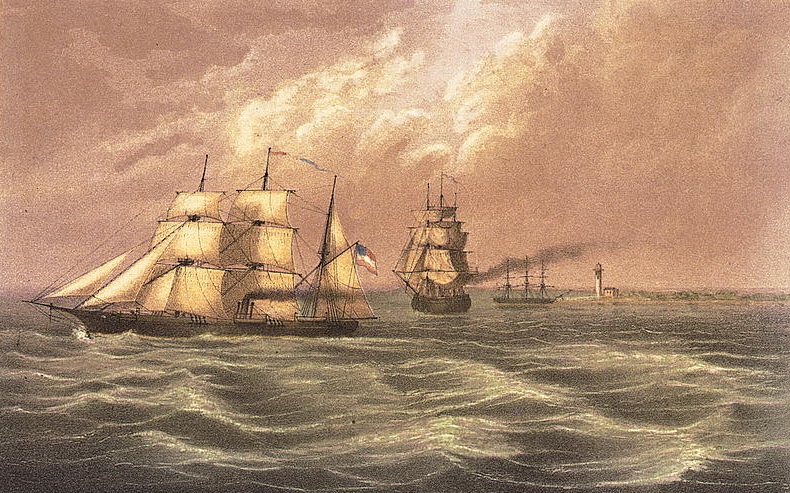

Semmes was an early advocate for commerce raiding and demonstrated its effectiveness by using a small packet steamer converted into the raider CSS Sumter to capture 17 prizes in six months.[6] With Sumter out of fuel, in need of repairs, and under the watch of Union warships at Gibraltar, Semmes paid off his crew escaped with some of his officers.

Acting with support from Confederate agents in England, Semmes helped man and provision CSS Alabama as a commerce raider to harass Union shipping across the world’s oceans.[7] Over the course of two years, Alabama haunted the high seas and sank, burned, or captured 64 American merchant ships in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans.[8]

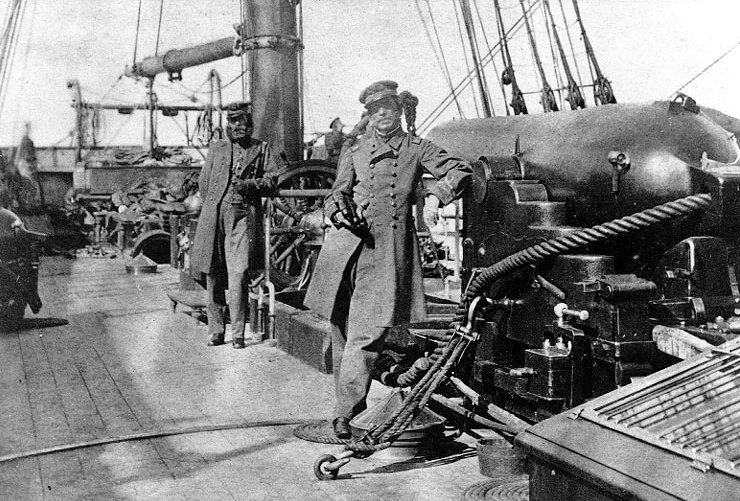

Semmes needed to rest and refit Alabama after many months of wartime patrolling and set into the harbor at Cherbourg, France.[9] USS Kearsarge, a Union warship, found and trapped her there in June 1864.[10] Despite being outgunned by the Union warship, Semmes chose to venture out and engage in a duel with Kearsarge. Alabama fought well and damaged Kearsarge, but eventually the latter’s advantages in armor and weight of shot won out and Semmes was forced to strike Alabama’s colors. With the ship actively sinking under them, the crew abandoned ship and Semmes and his officers were rescued by the British steam yacht Deerhound, which observed the action.[11] After this escape, and despite the fact that he had ostensibly surrendered with his ship, Semmes returned to the Confederacy, where he commanded a flotilla of gunboats outside of Richmond. After scuttling them during the fall of that city, he commanded a brigade of naval infantry, which he surrendered to Gen. William T. Sherman’s army in 1865.[12]

Analysis:

Semmes recognized that American trade networks were too vast to be effectively secured and that, with the Union fleet engaged in a blockade of the Southern coasts, his single ship could have an outsized impact on the war. This ability to recognize opportunities to leverage a small tactical force to achieve strategic outcomes is among the most valuable skills an irregular warfare practitioner can have. However, when Semmes was trapped at Cherbourg by Kearsarge, he viewed the situation as a matter of honor. Unlike at Gibraltar when his ship was unable to sail, he viewed any course of action other than sailing out to offer battle as cowardly.[13] Semmes was indoctrinated in both a Southern culture and a naval culture that taught him to hold honor as sacred, so he failed to account for other options that he did not view as honorable. This honor fixation meant that Semmes failed to successfully adapt. He viewed the arrival of a Union warship with superior armor and firepower as a purely military problem and tried to engage in a “fair fight” that he was doomed to lose.[14]

Despite the American press occasionally referring to Semmes as a “pirate”, the Union authorities eventually allowed that Semmes’s conduct throughout the war was legal.[15] Though he was arrested in December 1865 and initially charged with piracy, the Union authorities quickly recognized that such a charge could not be applied to Semmes’s actions. They then attempted to prosecute him for failing to adhere to the laws of war by escaping aboard Deerhound after surrendering his ship, but even this charge was eventually withdrawn when prosecutors assessed that they would be unlikely to successfully achieve a conviction.[16] Semmes was allowed to retire and become a local fixture of Mobile society, in which he maintained a well-earned reputation as a naval hero (and may have inspired Jules Verne’s famous Captain Nemo).[17]

However, Semmes’ post-war plight illustrated the legal and moral hazards of irregular warfare. His command was destroyed because he prioritized the conventions of naval honor over practicality, but he was imprisoned and had his post-war livelihood degraded because he had waged an irregular warfare campaign in the first place. Practitioners of conventional warfare often stigmatize irregular warfare as illegal, immoral, or unethical. Practitioners of irregular warfare must attempt to walk a fine tightrope. A disregard for law, ethics, and morality risks an irregular command becoming discredited as little more than a criminal gang, while zealously observing the rules imposed on irregular combatants by their conventional counterparts risks honorable defeat.[18]

Collin Hayward is an Army Officer and qualified Army Historian specializing in the study of irregular warfare. He holds a Bachelor of Arts degree from Virginia Tech and Masters degrees from American University and the Army Command and Staff College, where he was an Art of War Scholar. He has previously published an analysis of historical case studies in the InterAgency Journal titled “How to Win Without Fighting: Cold War Lessons on the Risks and Rewards of Political Warfare in Strategic Competition”.

Endnotes:

[1] Russell Blount, “Raphael Semmes: Patriot or Pirate?,” Mobile Bay Magazine, October 25, 2024.

[2] “U.S. Navy Brig Somers,” Naval History and Heritage Command, July 9, 2025, https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/ships/ships-of-sail/us-navy-brig-somers.html.

[3] Lawrence A Frost, “Dispatches from Grant,” Ulysses S Grant Presidential Library, January 1967.

[4] Blount.

[5] Spencer C Tucker, “CSS Alabama and Confederate Commerce Raiders in the American Civil War,” essay, in Commerce Raiding Historical Case Studies 1755-2009 (Newport , RI: Naval War College Press, 2013), 73–89.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Raphael Semmes, The Confederate Raider Alabama (New York, NY: Fawcett Publications, 1962), 44.

[8] James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 547.

[9] Semmes, 362.

[10] McPherson, 547.

[11] Semmes, 382.

[12] Semmes, 436.

[13] Semmes, 368.

[14] Semmes, 369.

[15]MacPherson, 316..

[16] John A. Bolles, “Why Semmes of the Alabama Was Not Tried (Part I),” The Atlantic, July 1872.

[17] Jules Verne and William Butcher, Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas (Oxford: New York?: Oxford University Press, 1998), 442.

[18] Collin Hayward, “Foul, Brutal, Savage, and Damnable: Quantrill’s Raid on Lawrence and the Pitfalls of Reciprocal Violence,” Emerging Civil War, July 8, 2025.

Excellent and thought-provoking report.

Privateering was discussed in De Bow’s Commercial Review (1847) as “an accepted technique to be used in war, with authority granted by the leadership of the nation.” So it was no surprise that a few years later the slavery-friendly Franklin Pierce Administration declined to sign the Paris Declaration Respecting Maritime Law of 16 April 1856, after an attempt by the Americans to insert a reference to “all private property” (i.e. slaves) was rejected by the parties that ultimately signed the document. Without this legal loophole – NOT being a signatory to the Declaration of April 1856 – Semmes’ actions, and those of his comrades engaged in chasing down unarmed merchant vessels would have legally been condemned.