“The camp must be held!”: Morgan’s Raiders at Camp Dennison

Link to previous post: Morgan’s Raiders in Glendale, OH

The residents in the Queen City—Cincinnati—breathed a sigh of relief that Morgan’s raiders had bypassed the city, leaving it mainly intact. Unfortunately for others in Ohio, the ordeal was not over.

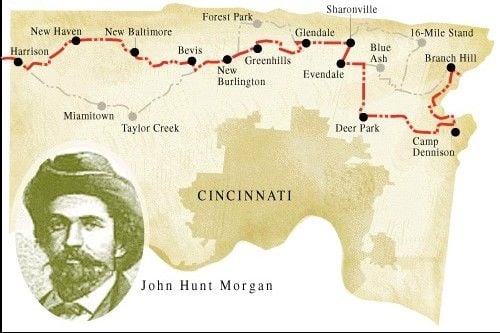

Around 4:00 a.m. on July 14, 1863, Morgan’s men once again separated into two main columns. General Morgan

accompanied the southern column, heading toward Camp

Dennison, while Colonel Basil Duke headed north towards Loveland, Ohio. Along the southern route sat the home of John Schenck, a local pharmacist. The Schenck family received word of Morgan’s approach and attempted to hide their horses in their home and told the encroaching soldiers that a small child was ill with smallpox. It is unclear if the ruse worked; by some accounts, the raiders searched the farm, finding only a few workhorses. However, others reported General Morgan ate breakfast in the home. No evidence solidly supports either set of events, other than the Ohio Commissioners received no reports of stolen horses from the farm. After departing the Schenk farm, Morgan and his men continued along their southern route before Camp Dennison.

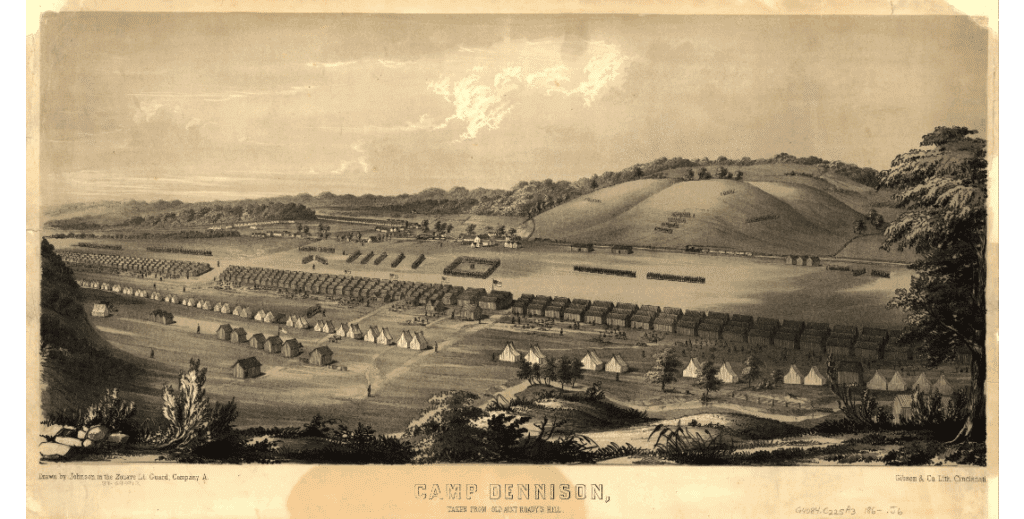

On April 27, 1861, Major General George B. McClellan had established Camp Dennison at Governor William Dennison’s request. The camp served as a site to muster, train, and discharge volunteer soldiers. Between 75,000 and 100,000 Union soldiers passed through Camp Dennison during the Civil War. In April 1862, the army added a hospital with 2,300 beds, making it one of the largest military hospitals in the Union. By July 1863, Camp Dennison sat at a strategically important crossroads but housed fewer than 600 men, most of whom recovered from wounds or had just joined the ranks. With Morgan’s arrival imminent, the camp began to prepare for an attack. As Morgan skirted Cincinnati, Lieutenant Colonel Neff, ordered Captain Joseph Proctor and fifty of his men to dig rifle pits in the main crossroads of Kugler Mill, Loveland, and Camargo Roads. Additionally, the men cut trees to cloak the roads. Protecting the camp was of utmost importance. Brigadier General Jacob D. Cox sent simple yet direct orders to Lt. Col. Neff which stated: “The camp must be held!”

Multiple correspondences between Camp Dennison and Gen. Ambrose Burnside flooded the area, trying to monitor all

of Morgan’s movements. However, this proved difficult to do. As Neff acknowledged in a report to Burnside: “The great difficulty is the country around here is cut up with roads. It is hard to tell what their intentions are.” Nearly 1400 men arrived at Camp Dennison a day before Morgan’s approach, but unfortunately few were armed. A fight at Camp Dennison could prove fatal for the Union position at Cincinnati. Neff wrote to Burnside again as Morgan’s men appeared, stating: “They have their artillery in position, bearing on the camp, on the north side of a hill. Their intention may be to burn the railroad bridge.”

As the Confederates approached the camp, Morgan and his men received a 600-gun salute. Morgan returned the “compliment”, ordering his artillery to fire on the camp using two 12-pounder howitzers. He hoped the barrage would disperse the Union troops, but it failed. Recognizing that a battle at Camp Dennison would be too costly with the Federals, well protected in their fortifications, Morgan bypassed the camp, heading north to cross the Little Miami River.

Unfortunately for the rebel general, crossing the river proved costly. Soldiers from the Ohio State Militia entrenched to protect the bridge and blocked Morgan’s northern route. Meanwhile, 150 men from the 18th U.S. Infantry trailed the Confederate rear guard, adding pressure to the enemy. The raiders faced a dire predicament, taking fire from both the front and rear. They scrambled for cover and searched for an alternate route across the river. Realizing that crossing at Miamisville was impossible, Morgan led his raiders two miles upstream and crossed the river without interference. During the hour-long shootout, Henry Meyers of Company D, 5th Ohio, died. Union forces also captured five raiders, including one of Morgan’s lieutenants.

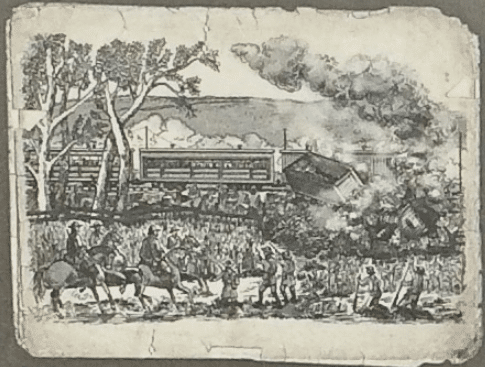

After fording the river, Morgan and his men came upon the Little Miami Railroad.

Creating an obstruction from crossties and a cattle guard found on a nearby farm, the Confederates lay in wait. Before long, they heard the low whistle of an approaching train. The rebels waited and, as the train approached, opened fire. Attempting to outrun the bullets, the train’s engineer, John Redman, increased the speed, not knowing that just up ahead the tracks had been blocked. Unable to stop in time, the train crashed into the blockade, sending railcars in multiple directions; only those towards the train’s rear remained on the tracks. The impact killed the train’s fireman, Cornelius Conway, and left Redman critically injured. The others on board were taken prisoners, including 150 new recruits headed to Camp Dennison. Morgan quickly paroled all those captured and sent them on their way, marching the rest of the way to the camp.

While Morgan continued making his way north, Colonel Duke led his column toward Montgomery, raiding every noticed farm in search of fresh horses. One farm belonged to Nicholas Todd. There, the rebels “traded” their worn-out horses for healthy ones, taking four horses, a buggy, and a set of harnesses from the Todds’ barn and leaving behind their tired mounts. For the Todd family, the exchange turned out to be a blessing in disguise. Once the Kentucky horses regained their strength, they proved to be exceptional racers. For generations, the Todds ran a successful horse track and stables. Similar stories linger in oral tradition and primary sources all across southern Ohio.

By 8:30 in the morning on July 14, 1863, both Morgan and Duke’s columns crossed the Little Miami River, eventually reuniting and continuing southeast.