On the Road to Atlanta: Who’s in charge?

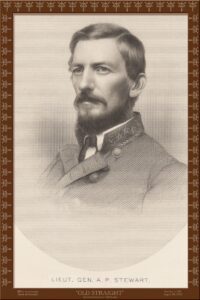

By July 19, 1864, John Bell Hood had firmly grasped the reins of his new command, the Army of Tennessee-now poised on Atlanta’s doorstep. Among his first challenges was a pressing personnel issue that needed resolution: who should take charge of his corps? Until recently the ablest major general in that command was Alexander P. Stewart, but he had just replaced the deceased Bishop Polk. And while Hood already had no high opinion of the ability of Maj. Gen. Thomas C. Hindman, that divisional commander’s recent illness rendered the prospect of Hindman taking command moot, for he was now on sick leave. Thus, two of the corps’ three divisions were in the hands of newly promoted brigadiers; good soldiers to be sure, but they had yet to be tested at higher command. Major General Carter L. Stevenson was now the ranking officer, and the only remaining divisional commander with experience, but Hood did not favor him, either. As he explained to Secretary of War Seddon that morning, “I need a commander for my old corps. . . [but] I have no major general in that corps whom I deem suitable for the position.” Instead, after consulting with Hardee, Hood chose Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham for the job, at least temporarily, “although he did not desire it.” As a result, however unwillingly, that very morning Cheatham turned over command of his division to Brig. Gen. George F. Maney and rode over to take up his new duties.[1]

Given Cheatham’s reluctance to leave his division, in that same dispatch the new army commander asked for one of three men be sent to him as a permanent replacement. His first choice was an officer close at hand, who had been well-regarded by Johnston and most of his subordinates: “Major General Mansfield Lovell might be assigned here to the great advantage of this army.” Alternatively, if a “lieutenant general was to be appointed and sent to me,” he continued, “I know of no one that I would prefer to Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton or S. D. Lee.” Though presumably Hood now had President Davis’s favor and could exert more influence with Richmond than could Johnston, Lovell remained persona non grata. Seddon ignored the request, and Lovell’s name was not mentioned again. Next was Wade Hampton, a fabulously wealthy South Carolina planter who had also proved himself to be a capable officer in the Army of Northern Virginia. Hampton once commanded an infantry regiment in Hood’s brigade, in 1862; until taking command of a cavalry brigade, and later, a full division. Both Hood and Hampton were wounded at Gettysburg and subsequently shared the same ambulance on the long ride back to Virginia. However, the legendary J. E. B. Stuart’s recent death in May 1864 thrust Hampton into command of Robert E. Lee’s Cavalry Corps, where he again excelled. Lee now needed him desperately and was not about to let him go.[2]

The last choice was Stephen Dill Lee, another former Army of Northern Virginia man, currently commanding the Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana. However, Lee lacked experience at higher command. He commanded an artillery battalion under James Longstreet, fighting effectively at Second Manassas and Antietam, until he was transferred west. He commanded an infantry brigade at Champion Hill, until Pemberton returned him to overall artillery command at Vicksburg. Paroled and exchanged, he was again transferred to the cavalry, where he led a cavalry brigade and division in Mississippi. When Leonidas Polk took all the infantry and a cavalry division to join Johnston in Georgia, S. D. Lee’s rank elevated him to command of the department in Polk’s absence. But Lee was seriously deficient in experience at higher command, especially of infantry; a want clearly demonstrated by his inept performance at Tulepo on July 14 and 15, just a few days previous. Still, despite his inexperience and his errors on the battlefield, Lee got the promotion and the job. However, he would not be able to join the army and take up his new assignment for nearly a week, especially given that Union cavalryman Lovell H. Rousseau was currently rampaging through Alabama.[3]

At least three officers almost certainly felt slighted by Cheatham’s selection: William W. Loring, Carter Stevenson, and W. H. T. Walker—Loring doubly so, since he had just been passed over by Stewart. Though Loring had his difficulties with superiors in the past—notably with Stonewall Jackson in Virginia in 1861, and with John C. Pemberton in Mississippi in 1863—he was steady under fire and had been reliable divisional commander under Polk; indeed almost all of the officers in Polk’s command had petitioned for him to take charge of the corps after Polk’s death. Johnston, however, declined to choose him, though the army commander never explained why. William Walker did not live long enough to express his opinion on the matter, but he had been a major general since May of 1863, promoted at Joe Johnston’s personal insistence, with Johnston then claiming that Walker was “the only officer in his command competent to lead a division.” Walker also commanded the Reserve Corps under Braxton Bragg at Chickamauga.

Once again, however, his old army friend Hardee ignored him to recommend someone else. Carter Stevenson had similar command tenure, having served in southwest Virginia in 1862 and taken part of Bragg’s incursion into Kentucky that fall, before his very large division (almost 10,000 men) was transferred to Vicksburg just before the Battle of Stones River. In 1863, Stevenson’s command fought hard at Champion Hill and during the siege of Vicksburg until the surrender of that place. While Stevenson could claim no spectacular battlefield victories, he had as often as not been placed in impossible tactical situations by circumstances or the poor decisions of senior officers. Finally, it is worth nothing that if Johnston had promoted Loring in Polk’s place instead of Stewart, the latter officer would have remained in Hood’s corps either to take charge, or at least provide stable divisional leadership when Hood was unexpectedly thrust into army command on July 18.

And stable leadership was at a premium. As the army prepared for its first battle under John Bell Hood, two out of three corps were under new commanders (Leonidas Polk having been killed on June 14.) Further, four of the army’s ten infantry divisions also had new leadership: one replacement coming in June and three more since the beginning of July. Were these men ready for the challenges to come?

[1]OR 38, pt. 5, 892. Hood never explained the reason why he found Stevenson wanting. Stevenson had served under Hood since the latter’s arrival at Dalton in March; presumably Hood’s unfavorable impression of his corps officers—the Vicksburg rejects—did not improve over time. Stevenson had also unfairly earned the enmity of Braxton Bragg during the Chattanooga campaign for being driven off Lookout Mountain on November 24, 1863; and Bragg’s opinion might have also influenced Hood.

[2]OR 38, pt. 5, 892; Edward G. Longacre, Gentleman and Soldier: A Biography of Wade Hampton III (Nashville, TN: 2003), 157. Mansfield Lovell had been acting as a volunteer aide to Johnston since the beginning of June, and most recently had been supervising the Georgia Militia’s defenses of the Chattahoochee Crossings farther downstream. For his problems with Davis, see Powell, Atlanta Campaign, I: 80-81.

[3]Warner, Generals in Gray, 183, For Lee’s performance at Tupelo, see Edwin C. Bearss, with David A. Powell, ed. Outwitting Forrest: The Tupelo Campaign in Mississippi, June 22-July 21, 1864 (El Dorado Hills, CA: 2023.)