The American Bastille

On a recent visit to our nation’s capital, I found myself standing at the intersection of First and A streets, just east of the U.S. Capitol Building. Before me was the impressive United States Supreme Court Building. Constructed in 1935, it is the building where our country’s laws are interpreted. On its portico are inscribed the words “Equal Justice Under Law.” It wasn’t until later that I learned that during the Civil War another government building had stood on that exact spot – the Old Capitol Prison. It would become the most significant prison in Washington.

In the early 1800s a red brick tavern and hostel called Stelle’s Hotel stood on the site. The tavern and hotel later closed due to poor management. In August 1814, the British invaded Washington and burned the Capitol building. Without a meeting place, Congress looked for temporary quarters. A group of Washington real-estate investors heard rumors that Congress was considering relocating to another city. Realizing how that move would affect land values, the group offered to buy the land where Steele’s stood, raze the building, and construct a three-story brick building in Federal style that Congress could use. Congress readily agreed to the plan.[i]

As restoration to the Capitol Building commenced, the Congress and the Supreme Court moved into the completed brick building in December 1814. Known as “The Old Brick Capitol,” the name was shortened to “Old Capitol.” On March 4, 1817, President James Monroe was inaugurated in the Old Capitol. By 1819 the restored U.S. Capitol Building was opened, and Congress and the Supreme Court returned.

For a while, the Old Capitol Building was used as a private school. It was later sold and refurbished into a 40-50-room fashionable boarding house, patronized by the ‘crème de la crème’ of Southern dwellers in Washington. Some in Washington said that it was run by Rose O’ Neal Greenhow’s aunt. South Carolina Senator and Vice President of the United States John C. Calhoun resided there until his death in 1850. United States naval officer Commodore Stephen Decatur resided there before building a large home on Lafayette Square.

Other boarding houses, patronized by government officials, sprang up around the Old Capitol Building. One nearby was converted from the private residence of a man named Carroll. Another row house known as Duff Green’s Row House stood on the site of the present-day Library of Congress. A young Congressman from Illinois by the name of Abraham Lincoln stayed in one of these row houses from 1847-1849.[ii]

By the mid-1850’s, the Old Capitol Building was abandoned and fell into disrepair. It became dilapidated with its walls decaying, its doors, floors and stairs creaking, and its windows boarded up with wooden slats nailed across them. In 1861, the Old Capitol Building was purchased by the government and transformed into a prison. The wooden slats were replaced by iron bars, the interior remodeled, and the doors to the rooms fixed with secure locks. A high board fence enclosed the open areas between buildings, and extensions were built on the back and sides for a mess hall and additional quarters. Historian Allan Nevins described the Old Capitol Prison as:

A decaying jail hastily refurbished for captured Confederates, refugee Negroes, blockade runners, and state prisoners. The verminous rooms stank of open drains, sweating inmates and the eternal fare of salt pork, beans, and rice. A military guard clattered its arms on the cobblestones outside while patrols thumped up and down the wooden hallways. The dark, ill-ventilated cells, kept full to bursting, became breeding places for all kinds of maladies. During 1862 a midsummer influx of captured Confederates raised the population to 600. The only redeeming feature of this ramshackle barn was its convivial jollity, for most prisoners were herded into five large second-story rooms, partitioned out of great chambers which had been occupied by Congress . . . .”[iii]

When prisoners were brought into Old Capitol Prison, they were processed in a large room on the first floor. They were searched and questioned. Colonel N. T. Colby, one of the prison commandants, was astounded by the number of pocket-knives that were confiscated from incoming prisoners – an entire full bushel.[iv] From there they were escorted by the guards to their cells. These rooms were usually on the second floor where they had been used as chambers for the House of Representatives. One prisoner described the room:

Large and divided from the room in the front by folding doors, which were locked, and barred on the other side. Two windows without blinds opened on a large yard . . . The room was one of mass dirt; spiders-webs hung in festoons from the ceiling and vermin of all kinds ran over the floor. The walls had been papered, but dampness had caused most of it to fall off, which all over that which was left were great spots of grease . . .. The furniture consisted of an iron bedstead, pillows, and a mattress of straw, a pair of sheets, and a brown blanket.[v]

The vermin found in the Old Capitol Prison included rats, spiders, cockroaches, lice and bed bugs. Captain James N. Bosang complained that: “I could see them [bedbugs] by the hundreds all over me [and] all over my bed.” Ingeniously he placed cups filled with water under the legs of his bed and discovered “very few that even attempted to swim and they were drowned.”[vi] But as one historian recorded, “As foul and uncomfortable as the prison was, prisoners in Old Capitol were better off than many inmates housed at other penitentiaries. Unlike many Civil War prisons, inmates at Old Capitol were served meals three times a day. These usually consisted of unsavory pork or beef, half boiled beans and musty rice. And although the meals served in the dirty mess hall varied little from day to day, captives in Old Capitol Prison suffered less from malnutrition and from intestinal tract disorders that did inmates in other Civil War prisons.”[vii] Unfortunately for the inmates, the cookhouse was situated near the open, uncleaned sinks from which the stench permeated throughout the prison.[viii]

Old Capitol Prison was designed for 500 inmates, and by October 1861, it was full. The incarcerated included soldiers captured from First Bull Run and Fairfax Court House, blockade runners, political prisoners, spies, Union officers convicted of various crimes, bounty jumpers, counterfeiters, local prostitutes and contrabands. The contrabands were soon segregated to Duff Green’s Row Houses.

By mid-1862, with the annexation of Duff Green’s Row House and the Carroll House Prison, the population of prisoners rose to 1,500. The most ever held there at one time was 2,763. “According to the official records a total of 5,761 POWs were held at Old Capitol Prison of which 457 died.” [ix]

Some of the more famous inmates included 19-year-old Belle Boyd, who taunted the guards by singing Confederate songs at her window. One prisoner found that when she sang “Maryland, My Maryland” he had to avert his face so the other inmates did not see the tears welling in his eyes.

Another famous prisoner was Rose O’Neal Greenhow, the infamous spy who relayed the Union plans of advance to Manassas to General Beauregard in 1861. She took her 8-year-old daughter to jail with her, and because the child could come and go as she pleased, Greenhow began using her as a courier, continuing to pass information to the South. One of her frequent visitors was Senator Henry Wilson who she supposedly informed her of McDowell’s impending advance.

The highest-ranking Confederate general to spend some time in Old Capitol Prison was Edward “Allegheny” Johnson. His stay was brief before he was transferred to other prisons. As a captain in 1862, John S. Mosby was surprised and captured by Union cavalry while waiting for a train at Beaver Dam Station. He was taken to Old Capitol prison and spent 10 days there before he was exchanged.

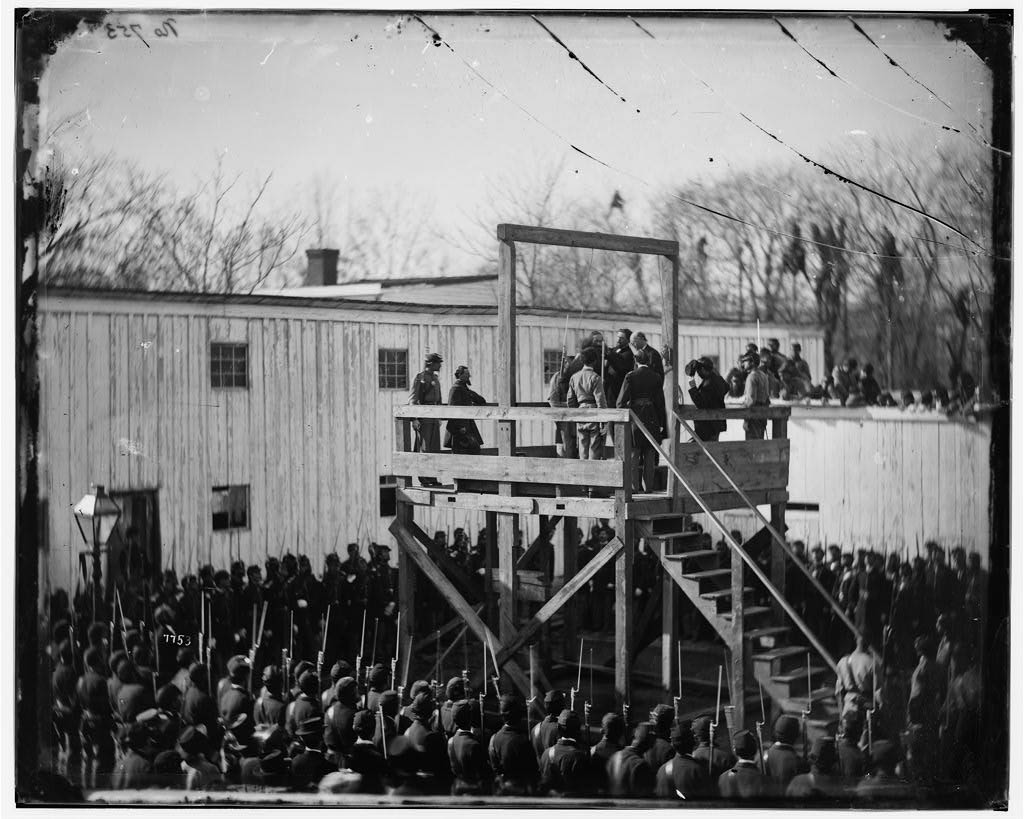

In 1865, some of Mosby’s Rangers were held there as well as those people implicated in Lincoln’s assassination such as Dr. Samuel Mudd, Ned Spangler, Mary Surratt, Louis Weichman, John Llyod, John T. Ford (the owner of Ford’s theater), and Junius Brutus Booth, (the brother of Lincoln’s assassin John Wilkes Booth). After the war, Confederate Governors Vance of North Carolina, Letcher of Virginia and Brown of Georgia spent some time in Old Capital. The commandant of Andersonville Prison, Capt. Henry Wirz, was held there during his trial. When found guilty of war crimes against Union prisoners. Wirz was hung in the Old Capitol’s cobblestone courtyard. [[x]

There were 60 guards under a captain or lieutenant daily detailed for the prison, and a number of commandants were in charge of the prison during the war. One was William P. Wood. Appointed to the post by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton in January 1862, Wood, acting more as an interrogator than as a warden, frequently interrogated inmates to gain information. He also scrutinized their mail and any critical information discovered was sent directly to Stanton. Prisoners had to be careful as Wood had spies posing as prisoners circulating amongst them trying to gain information.

There were no means at Old Capitol Prison to punish prisoners when they broke any rules. There was no dungeon or solitary confinement, but the guards were very strict. [xi] They patrolled the outside of the prison and “No person was allowed to show any sign of recognition. If a person was seen loitering in passing the prison, or walking at a pace not considered satisfactory by the guard, he soon received a peremptory command to ‘pass on’ or ‘hurry up there,’ and if this warning was not heeded the offending person whether male or female was arrested and detained.”[xii] Prisoners could look out their windows, but were not allowed to touch the bars. This didn’t stop one guard, after repeated warnings, from shooting and killing an inmate who refused to vacate his window.[xiii]

Unlike other prisons, guards not only walked a beat outside on the street, but also inside. The prisoners were locked in their cells most of the day and only were free at meal times. In their locked cells, the prisoners could hear “the steady tramp of the sentry up and down the halls all night, clanking of arms, challenging of the guards and the calls of the relief.”[xiv]

Apparently some guards were careless with their weapons as prisoners sometimes heard the report of a musket inside the building. One prisoner was in his bunk talking with his roommates when he heard a sharp report from the room below. Simultaneously a bullet passed up through the floor going through the slats in his bed, through his blankets and pillow, barely missing his head, before continuing through his ceiling. The accident was reported, but nothing came of it.[xv]

Prisoners learned to avoid Lieutenant Holmes of the guards. Nicknamed “Bullhead,” Holmes would slap and kick prisoners, both Union and Confederate. On one occasion he even entered a guardhouse where a sentry was incarcerated for being drunk and noisy, and Holmes slapped and kicked the sentry several times.[xvi]

There were few escapes – only sixteen- from Old Capitol Prison. One inmate fashioned a rope from his blanket and lowered himself out a second-floor window. Unfortunately the rope was not long enough, and he had to drop the rest of the way, landing almost at the foot of a guard. The guard aimed his musket at the man, but his cap failed to snap and fire the gun. The prisoner escaped only to be returned a month later when he was caught in Baltimore. Another inmate tried to bribe a guard to let him climb out a window and lower himself with a rope. When the inmate was halfway down, the guard called out to his comrades that a prisoner was trying to escape and shot at the man shattering his kneecap. The inmate was hoisted back up into his cell by his roommates and later died after his leg was amputated.[xvii]

After the war, the government sold the Old Capitol Building in 1867 to George T. Brown, then sergeant-at-arms of the U.S. Senate. He modified the building into three row houses known as “Trumbull’s Row.” In the early 20th century the National Women’s Party used it as their headquarters. In 1929 the site was acquired by eminent domain and the building razed to clear the site for the U.S. Supreme Court Building.[xviii]

There is a lot of hidden history in Washington D.C. if you know where to look. Today, standing and looking at the majestic Supreme Court Building, my imagination can conjure the sight of the three-story Old Brick Capitol Prison and picture looking up to its barred windows and catching the furtive glances of its inmates while the sentries below walk their posts and tell me to “pass on” and “hurry up there.”

[i] Harold, H. Burton & Thomas E. Waggaman, “The Story of the Place: Where First and A Streets Formerly Met and What Is Now the Site of the Supreme Court Building,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington D.C., Vol. 51/52, 1951/1952. Speer, Lonnie R., Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, 1997. p. 41

[ii] McClure, Alexander Kelly, editor, The Annals of the Civil War: Written by the Leading Participants North and South, “The Old Capitol Prison” by Colonel N.T. Colby, Da Capo Press, New York, 1994. Pp. 502-512. Faust, Patricia L., editor, Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War, Harper & Row Publishers, New York, 1866. p. 544. Leech, Margaret, Reveille in Washington, 1860-1865, New York, Time Incorporated, 1962. P.167.

[iii] Nevins, Allan, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution: 1862-1863, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1960. p. 312. Speer, Portals to Hell, p. 41.

[iv] Colby, The Old Capitol Prison, p. 504.

[v] Lomax, Virginia, The Old Capitol and its Inmates, E. J. Hale & Son, New York, 1867. pp. 66-67. Qunit, Ryan T., Dranesville: A Northern Virginia Town in the Crossfire of a Forgotten Battle, December 20, 1861, Savas Beatie,El Dorado Hills, California, 2024. pp. 98-99.

[vi] Bosang, James N., “Chinch Harbor”, A Civil War Treasury of Tales, Legends, and Folklore. Ed. Benjamin A. Botkin, New York, Promontory Press, 1960. pp. 445-447

[vii] Heidler, Davis Stephen, Jeanne T. Heidler, editors, Encyclopedia of the American Civil War, W. W. Norton & Company, New York & London, 2000. Entry “Old Capitol Prison”, Alicia Rodriguez, pp. 1432-1434

[viii] Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 174

[ix] Speer, Portals to Hell, pp.329, 310. O.R. Vol. VIII, pp.990-1004 Carroll Prison Annex was torn down and is now the site of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

[x] Colby, The Old Capitol Prison, pp. 507-510. Ramage, James A., Gray Ghost: The Life of Col. John Singlerton Mosby, Lexington, Kentucky, The University Press of Kentucky, 1999, p. 51 Speer, Portals to Hell, pp. 82, 291-292, https://lincolnconspirtors.com/2013/04/17/imprisoned-at-old-capitol-prison/

[xi] Speer, Portals to Hell, p. 82. Mahoney, D.A., The Prisoner of State, New York, Carleton Publishing, 1863. pp. 29-30.

[xii] Williamson, James J, Prison Life in the Old Capitol, West Orange, New Jersey, Williamson Publishing, 1911. pp. 26-27

[xiii] Ibid. pp 26-27

[xiv] Ibid. pp. 25.

[xv] Mahoney, D.A., The Prisoner of State, p. 316. O.R. Vol. V, pp. 118, 316-317

[xvi] Speer, Portals to Hell, pp. 84, 164

[xvii] Speer, Portals to Hell, pp. 83, 329. Colby, The Old Capitol Prison, pp.505-506

[xviii] Harold & Waggaman, “Story of the Place.”

Brian, very interesting. The speed at which the building was constructed is particularly impressive.

The history of The Old Capital prison gives new context to today’s “shadow docket” of SCOTUS.