The Secessionist Coup D’état Aimed at the 1861 Virginia State Convention & What Might Have Been

April 1861: The country is in crisis. Seven states have left the Union. Others teeter on secession’s brink. Competing factions clash. Passions reach fever pitch. While some counsel patience, violence erupts. Shots are fired. A chief executive appeals for troops to put down an insurrection against his government. A new president heeds that call. Soon federal troops are pouring into Virginia to support an embattled Governor John Letcher, who is facing an armed rebellion led by his predecessor and mutinous state militia. A civil war within a civil war has erupted.

Fantasy? Hardly. In the weeks leading up to the firing on Fort Sumter, those in Virginia who most strenuously argued for secession grew frustrated and increasingly angry over the failure to get their way. A faction of that pro-secession movement decided that if political persuasion would not work, violent action was justified. And they came within days, perhaps hours, of putting into effect a violent coup intended to overthrow Virginia’s government and lead the state into war. Indeed, elements of their plan involving armed force were actually put into motion.

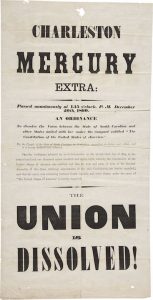

Virginia’s secessionists ultimately prevailed in their crusade to take the Commonwealth out of the Union. In response to Abraham Lincoln’s April 15 Proclamation of Insurrection and call for troops to suppress rebellion after the firing on Fort Sumter,[1] on April 17, 1861 a Virginia State Convention adopted an ordinance of secession.[2]

Yet up to that point the secessionists had suffered a string of political defeats at the hands of the pro-Union faction, which until the very end seemed to represent the will of the majority of Virginians. In the 1860 presidential election, for example, Virginia had endorsed Constitutional Unionist candidate John Bell of Tennessee, whose entire campaign stressed preserving the Union.[3] As described below, Virginia’s secessionists subsequently lost other key political battles.

South Carolina’s secession on December 20, 1860 sparked a political crisis. Within weeks, six other deep South states followed South Carolina out of the Union. A pro-secessionist faction in Virginia demanded that Virginia immediately join her departing sister states.

Yet a substantial portion of the Commonwealth resisted, preferring a “wait and see” attitude while seeking an accommodation defusing the crisis. Governor Letcher agreed, calling for a national conference of all states to meet in Washington to hammer out a compromise. Secessionists were furious, referring to Letcher as the “Tortoise Governor.” [4]

Seeking to push forward as quickly as possible, the hotheads persuaded the legislature to call a state convention to consider the secession question. But even this apparent victory was illusory. The authorizing legislation directed voting for delegates in a democratic manner the secessionists opposed. Worse (from the secessionists’ perspective), the legislature suggested requiring a referendum confirming any convention action. The ensuing election sent a Unionist majority to the convention, while demanding that any secession decision be ratified by referendum.[5]

The convention convened in Richmond on February 13. It elected John Janney, a firm Unionist, as president.[6] Janney presided as arguments over Virginia’s course of action commenced. Meanwhile, secessionist anger simmered. “[G]roups of young men…began to roam the streets of Richmond, promoting secession and threatening those who opposed.” At one point O. Jennings Wise, son of former governor Henry Wise, declared that if the convention failed to endorse secession, “it ought to be driven from its hall at the point of a bayonet.”[7]

As convention delegates debated, the Washington Peace Convention (the conference Letcher had championed) met, compromise measures were offered in Congress, and Lincoln wrestled with the crisis, including what to do about the looming confrontation over Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. Convention representatives traveled to see Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward, seeking ways to keep Virginia in the Union. Through it all, the Unionists counseled moderation, rebuking the hotheads as seeking to lead Virginia into a war in which the Old Dominion clearly would be on the front lines. One of those Unionists was Robert E. Lee’s future trusted subordinate and “bad old man,” Jubal Early, who as late as April 13 (after news of the firing on Fort Sumter), defiantly warned that any Confederate “invasion of our soil [to attack Washington] will be promptly resisted.”[8]

In response, the secessionists harped on the failure of compromise attempts, the refusal of the Lincoln Administration to evacuate Fort Sumter (despite Seward’s private assurances), rumors that Lincoln was preparing for an invasion, and the supposed duty of Virginia to support its sister slave states. The increasingly charged environment, and perceived betrayal by Lincoln on the Sumter issue, emboldened the secessionists, who decided that the moment was right to force the issue.[9]

On April 4, Lewis Harvie, delegate from Amelia County, proposed a formal Ordinance of Secession. The secessionists believed that at last they were on the verge of victory. They were not. The convention decisively rejected secession, 90 to 45.[10] Just as bad, from the perspective of those who wished to sunder the Union, the convention kept looking for a peaceful way out of the crisis. On April 12, the convention called for a conference of the eight slave states that had not seceded to discuss how best to protect their interests (slavery) within the Union, rather than without. This meeting was to take place in Frankfort, Kentucky, in late May. Such delay was intolerable to the hotheads.[11]

Stung by their secession vote defeat, the most radical secessionists decided that if they could not prevail through legal means, another approach was needed. Led by Letcher’s predecessor, former governor Henry Wise, they announced plans for a new convention. Called the “People’s Spontaneous Convention,” invitations were sent to the most fervent secessionists.[12] J.B. Jones wrote in his soon to be famous diary: “Everywhere the Convention…was denounced with bitterness, for its adherence to the Union; and Gov. Letcher was almost universally execrated for the chocks he had thrown under the car of secession… And now I learned that a People’s Spontaneous Convention would assemble in Richmond on the 16th…, when, if the other body persisted in its opposition to the popular will, the most startling revolutionary measures would be adopted, involving, perhaps, arrests and executions. Several of the members of this body with whom I conversed bore arms upon their persons.”[13]

Nearly two hundred “Spontaneous” delegates gathered on April 16 in Metropolitan Hall, only two blocks from the Capitol.[14] By that time, however, the situation had changed dramatically.

On April 12, Confederates bombarded Fort Sumter, which surrendered the following day. The outbreak of war energized the secessionists. On April 14, gangs marched through Richmond with Confederate banners, loudly demanding that Virginia secede.[15] Still, Unionists hoped that they could delay matters until the Frankfort meeting.[16]

The Unionists’ adversaries were not about to give peace a chance. For weeks, pro-secession rowdies had harassed and “sometimes physically attacked Unionists throughout the state.”[17] Wise had clashed with Governor Letcher over the former’s insistence that Virginia prepare for war.[18] With war begun, Wise not only was ecstatic, but determined Virginia would join the fight.[19] And if that required extralegal means and even violence, Wise would not hesitate.

The time had come for action. The leaders of the Spontaneous People’s Convention decided that if the Virginia State Convention would not act as they demanded, it would be dissolved by force. These plotters planned to launch an armed coup to overthrow the state government. The governor and Unionist members of the Virginia State Convention would be arrested. Anyone who resisted would be subdued, by lethal force if necessary. Wise himself was prepared to take over the government and force Virginia out of the Union.[20]

Wise put aspects of his plan into motion. On April 16, Wise had urged Letcher to send state troops to seize the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry and Norfolk’s Gosport U.S. Navy Yard. Letcher refused. In response, Wise illegally ordered pro-secessionist militia officers into action against those targets. Wise was determined to present the Virginia State Convention delegates with the “fait accompli that Virginia had declared war on the Federal government.”[21]

Of course, the question was whether in the next few hours the Virginia State Convention still would be in existence or forcibly dissolved, its Unionist members arrested or worse. The coup plotters were on the verge of acting when Virginia’s world shifted.[22]

On April 15, Lincoln issued his Proclamation of Insurrection and call for troops. News of this action caused consternation among many Unionist delegates. Standing with the Union was one thing; joining it in war against their sister states was quite another. Wise recognized the changing momentum. He advised his fellow plotters to delay their coup. A new secession proposal was introduced, to be voted on April 17. Perhaps the coup would not be necessary.[23]

On April 17, Wise addressed the convention. He placed a pistol before him, a visible symbol of violence. His supporters ringed the convention’s meeting hall, shouting threats. Brandishing his revolver, Wise revealed that he had unilaterally (and illegally) ordered Virginia’s troops into action against the U.S., announcing that “blood will be flowing at Harper’s Ferry before night.” The time for debate was over, he warned. While some objected to Wise’s illegal action, Lincoln’s proclamation had fatally altered the calculus. The convention approved secession by a vote of 88 to 55. Virginians would not fight against their fellow Southerners; rather, they would fight their erstwhile government. “And the war came.”[24]

It is fascinating to consider the “what ifs” inherent in the foregoing story. By passing the Ordinance of Secession when it did, Virginia’s legally constituted convention dodged a bullet, perhaps literally. A coup was imminent, its leaders prepared to use violence to achieve their goal. Unionists were just as determined to uphold their principles. A bloody clash might have resulted.

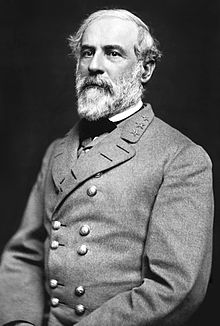

Had Lincoln withheld his proclamation by only 72 hours, thus delaying the last-minute decisive pro-secessionist shift it caused, the coup might have gone forward. Then Letcher might well have felt forced to seek support from the Lincoln Administration to restore order and suppress the intra-state insurrectionists. The obvious choice to lead federal troops into Virginia to restore order was Virginia’s Robert E. Lee, still a U.S. Army officer.[25] Even if Letcher declined to seek outside (U.S.) military assistance, Virginia’s descent into its own civil war probably would have precluded it from formally joining the Confederacy.[26] Certainly, Richmond would hardly have been in a stable position to become the new Confederate capital.

Momentous events may turn on timing. The timing of Lincoln’s action, coupled with the delay of the coup, provided just enough time for Virginia’s secession and subsequent union with the Confederacy. But for a mere matter of days, the results—and the course of the Civil War—might have been far different.

A version of this piece appeared in The Dispatch, the newsletter of the Roanoke Civil War Round Table.

[1] Lawrence M. Denton, Unionists In Virginia: Politics, Secession and Their Plan to Prevent Civil War (History Press, Charleston, SC 2014), p. 164.

[2] Denton, pp. 173, 178; “Union or Secession: Virginians Decide, Referendum on Secession,” Education @ Library of Virginia, https://edu.lva.virginia.gov/oc/union-or-secession/units/referendum-on-secession.

[3] Denton, pp. 55, 58, 59.

[4] Denton, pp. 68, 69.

[5] Denton, pp. 16-17, 71, 80 – 82, 95. Denton opined that at the outset of the Convention, some 20% were “immediate secessionists,” about 33% were staunch, or “unconditional” Unionists, and 47% were so-called “conditional” Unionists. Denton, p. 95.

The last group consisted of men who preferred to remain within the Union, but not at the expense of what they perceived as Southern states’ rights. Id. at 16-17, 95. See also Shearer Davis Bowman, “Conditional Unionism and Slavery in Virginia, 1860-1861: The Case of Dr. Richard Eppes,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 96, No. 1 (Jan., 1988), pp. 31, 32-34, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4248988 (defining “conditional Unionism” as those who objected to any coercion against secession and who insisted upon the rights of slaveholders, including the right to extend slavery into the federal territories).

[6] Denton, p. 97.

[7] Denton, p. 97; Nelson D. Lankford, Cry Havoc! The Crooked Road to Civil War, 1861 (Penguin Books, New York, NY 2007), p. 57.

[8] Millard K. Bushong, Old Jube (Carr Publishing Co., Boyce, VA, 1961), pp. 34-35; Denton, pp. 162-163.

[9] Denton, pp. 146-149, 151.

[10] Denton, p. 149; “The April 4, 1861 Vote on Secession: Prince William County Stands Alone,” All Not So Quiet Along the Potomac: The Civil War in Northern Virginia & Beyond, April 4, 2011,

[11] Denton, pp. 162-163, 167.

[12] Denton, p. 170; Lankford, pp. 114-115.

[13] J.B. Jones, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary At the Confederate States Capital (J. B. Lippincott & Co., Philadelphia, PA, 1866), pp. 15-16 (entries of April 10-11), https://www.gutenberg.org/files/31087/31087-h/31087-h.htm#CHAPTER_I.

[14] Denton, p. 170; Lankford, pp. 114-115.

[15] Denton, pp. 156, 166.

[16] Denton, p. 167.

[17] Denton, p. 170.

[18] Denton, p. 129; Lankford, pp. 127-128.

[19] Denton, p. 163; Lankford, pp. 121-122, 127-128.

[20] Denton, pp. 170-171; Lankford, pp. 115-116, 125, 127.

[21] Denton, pp. 172-174, 178; Lankford, pp. 127-129; Charles C. Osborne, Jubal: The Life and Times of General Jubal A. Early, CSA (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 1992), pp. 49-51.

[22] Lankford, pp. 125, 127.

[23] Denton, pp. 169-171.

[24] Lankford, pp. 121-123; Denton, pp. 173-174; Nelson Lankford, “Virginia Convention of 1861,” Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities (07 Dec. 2020). Last updated: 2025, February 18, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/virginia-convention-of-1861/; William W. Freehling, “Henry Wise’s Pistol,” The New York Times, April 16, 2011, https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/16/henry-wises-pistol/. “And the war came” is from Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, https://www.nps.gov/linc/learn/historyculture/lincoln-second-inaugural.htm.

Virginia’s secession was approved by a May 23 state-wide referendum. Lankford, “Virginia Convention of 1861.”

[25] Lee did not submit his resignation until April 20, after declining an offer to lead U.S. troops in subduing the insurrection. If, instead of approval of secession, violence had broken out in Virginia and its governor had appealed for assistance in upholding the laws of Virginia, it is certainly possible that Lee would have hesitated to resign until his sense of duty with respect to his home state had time to develop. Douglas Southall Freeman, R.E. Lee, vol. 1 (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, NY 1940), pp. 433, 435-437, 440-442; Robert E. Lee, Jr., Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee (Garden City Publishing Company, Inc., Garden City, NY 1924), pp. 24-25; Alan T. Nolan, Lee Considered: General Robert E. Lee and Civil War History (University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC 1991), pp. 37, 38.

[26] On April 25, the Convention approved a “temporary union with the Confederacy,” subject to the still-pending May 23 referendum to approve secession. Freeman, vol. 1, p. 487. Of course, had the Convention been dissolved by force, it could not have so acted.

Really great article and well researched!

Michael, thank you.

The Secession Crisis is often presented as one inevitable chain of dominoes. This article does well in breaking that illusion, while providing a fascinating story as well.

Fascinating.

Excellent detail. Had Lincoln not used subterfuge to elicit warning shots (equally detailed and documented series of events), and then called for troops to invade the South, it is very likely that Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas would have remained in the Union, increasing the likelihood of a viable workout, whether the Confederacy continued to exist or not. It’s never been any mystery that there were strong Unionist partisans in both States and that convention votes had consistently been against secession with no sign of a change of heart until Lincoln called for troops. Lincoln was being pressured by powerful figures in the North to wage a ‘quick war’, but he was well aware that his source of tariff income for the already troubled US Treasury was walking out the door and he somehow decided to make absolutely sure that happened, at the cost of a million lives, at least, and a century of ill effects. He was a smart, even brilliant, person but he did not have one shred of true statesmanship.

WRONG!!!!

Virginia seceded in April 1861, after the attack on Fort Sumter and President Lincoln’s call for troops, primarily to protect the institution of slavery, which the state’s ruling class saw as essential to its economy and way of life.

No subterfuge at all. Fort Sumter was a US installation and the war started when the Confederates fired upon it.

I think you’re both wrong. I don’t see any subterfuge in Lincoln’s actions. He was pretty clear about what he intended to do. On the other hand, it’s also clear Virginia seceded in response to Lincoln’s call for troops. The convention voted to remain in the Union previously. Many Unionists in western Virginia argued that Virginia should remain in the Union precisely to PROTECT slavery, which the federal government had done up until that point. Not everyone had identical motivations in backing or opposing secession, especially in Virginia.

Excellent article, Kevin. Well researched and very interesting. Loved the bit about Wise taking the gun into chambers.

Brian, thank you. Glad you enjoyed it.

Actually, Virginia seceded from the Union in April 1861 primarily to protect the institution of slavery and to assert states’ rights in response to the election of Abraham Lincoln, though it was initially reluctant to leave. The Confederacy’s attack on Fort Sumter and Lincoln’s call for federal troops to suppress the rebellion may have been the final catalyst, making Virginia’s delegates vote for secession to prevent war on Southern soil

The secession document of Virginia, known as the Ordinance of Secession, mentioned slavery as a cause for leaving the Union, stating that the Federal Government had “perverted said powers… to the injury of the people of Virginia, but to the oppression of the Southern slave-holding states”. While some seceding states issued separate, explicit “Declarations of Causes,” Virginia’s action was part of a larger pattern where slavery was a central reason for secession, as articulated in other state documents and speeches.

Wow — a fascinating article! Thank you, Kevin!