Known and Unknown: Civil War Balloonists and their Forgotten Monument

ECW welcomes guest author Eric Atkisson.

On May 31, 1962, a crowd that included schoolchildren, teachers, the mayor, and several out-of-town guests gathered at the Richmond, Virginia airport to unveil a new monument. Emplaced by the city the previous day, the gray, horizontal 4 x 12 marble slab was revealed with much fanfare on the battle of Seven Pines centennial, though it neither exalted Gen. Robert E. Lee, who took command of the Army of Northern Virginia during the battle, nor celebrated the Army of the Potomac’s subsequent withdrawal from the very gates of Richmond.

The monument was instead a tribute to the “Civil War balloonists, Union and Confederate, known and unknown, who against ridicule and skepticism laid the foundation for this nation’s future in the sky.” Listing the names of 48 Union men and 13 Confederates who served as aeronauts, assistant aeronauts, or members of their respective army’s balloon corps–as well as those who made ascensions in the balloons or encouraged their use–the inscription further noted that the monument was erected “On the field where a century ago, a battle raged as one of these pioneers served aloft.”

While the battle of Seven Pines, or Fair Oaks as it was soon known in the North, was indeed fought on much of the same ground now occupied by the Richmond airport and surrounding community of Sandston, the aerial pioneer serving aloft on the day of battle was about 11 miles north and hundreds of feet in the air, keenly observing Rebel troop movements through his telescope.

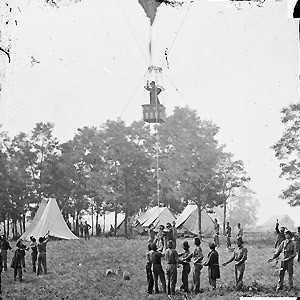

“On the 31st of May, at noon, I ascended at Mechanicsville, and discovered bodies of the enemy and trains of wagons moving from Richmond toward Fair Oaks,” wrote Professor Thaddeus S. C. Lowe, the Union Army Balloon Corps “Chief of Aeronautics,” as he signed his reports. “I remained in the air watching their movements until nearly 2 o’clock, when I saw the enemy form in line of battle, and cannonading immediately commenced.”[1] Lowe promptly dispatched an assistant with details of his observations to Maj. Gen. George McClellan and followed up with several written dispatches after returning to the army camp at the Gaines Farm.

McClellan, in response, ordered Maj. Gen. Edwin Sumner to hasten construction of a bridge across the Chickahominy and to march II Corps across as quickly as possible, in support of Maj. Gen. Samuel Heintzelman’s beleaguered III Corps. While these movements were completed just in time and the battle itself was a tactical draw, the Seven Days battles continued and McClellan ultimately withdrew the army to Harrison’s Landing.

In the final, official report of his service as commander of the Army of the Potomac, he fulsomely credited “Professor Lowe, the intelligent and enterprising aeronaut,” writing, “I was greatly indebted for the valuable information obtained during his ascensions.”[2]

“From my own observation and experience,” Heintzelman later wrote to Lowe, “I would consider your balloons indispensable to an army in the field, and should I ever be entrusted with such a command I would consider my preparations incomplete without one or more balloons.”[3]

“At all times we were fully aware that you Federals were using balloons to examine our positions,” Lt. Gen. James Longstreet wrote to Lowe years later, “and we watched with envious eyes their beautiful observations as they floated high in the air.”[4] Longstreet lamented the Confederacy’s own short-lived experiment with observation balloons, writing years later for Century Magazine, “We longed for the balloons that poverty denied us” and telling a fanciful story about a balloon stitched together from “all the silk dresses in the Confederacy.”[5]

The balloon in question, the Gazelle, was not in fact made of actual dresses, but of multicolored silk normally used for dresses, and manufactured at private expense in Savannah, Georgia.[6] Captured on July 4, 1862, the Gazelle was one of only two Confederate balloons launched during the war under the command of Capt. John Randolph Bryan, who unlike Lowe and his Northern colleagues had no previous experience as a balloonist.

Lowe himself resigned a year later, after the battle of Chancellorsville. Still suffering the lingering effects of malaria contracted on the Peninsula, he had quarrelled with army and government bureaucracy, ambitious rivals in the Balloon Corps, and his newest army superior, who cut the balloonists’ pay and demanded that Lowe’s father, an assistant aeronaut, be discharged from the service. The Balloon Corps continued for a few months without Lowe, but was officially disbanded in August 1863, much to the Rebel army’s relief.

“I have never understood why the enemy abandoned the use of military balloons,” wrote Col. E. P. Alexander, who had ascended in the Gazelle with Bryan only days before the balloon’s capture. “Even if the observers never saw anything they would have been worth all they cost for the annoyance and delays they caused us in trying to keep our movements out of their sight.”[7]

While Lowe was recovering at home, he was visited by a young engineer officer of the Württembergian army named Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin. Inspired by what he had seen as a Union army observer in 1863, Zeppelin consulted with Lowe at length on his experiences and knowledge of balloons.

Years later, as a German general and inventor of rigid airships, he credited his observations in the American Civil War as the origin of his inspiration for dirigibles. During the First World War, German “Zeppelins” drifted in the skies over England on reconnaissance and bombing runs, while hundreds of tethered observation balloons rose along both sides of the Western Front in Belgium and France. More recently, unmanned tethered balloons called aerostats have provided critical surveillance and security for American and allied military forces in places like Iraq and Afghanistan.

The balloonists of the American Civil War were ahead of their time. They hadn’t just “laid the foundation for this nation’s future in the sky” as the Richmond monument rightly claims; they had laid the world’s as well. Lowe himself, a prolific inventor with 18 U.S. patents to his name, is credited with designing the first portable gas generators for balloons and the first aircraft carriers–used to good effect during the Peninsula Campaign–as well as the first-ever use of telegraphs from the air and novel improvements to the altimeter, aerial mapping techniques, and the balloons themselves. All had a lasting impact in the field of military aviation.

Fittingly, descendants of Lowe and Bryan were on hand to participate in the unveiling of the Civil War Balloonists Monument on May 31, 1962. From 1986 to 2016, it shared the site with the Virginia Aviation Museum, until the museum was shut down, its collections dispersed, and the building itself later destroyed. Today the spot where the museum once stood is a concrete mixing site for an FAA safety improvement project on the airport’s taxiways, and there are no definitive plans for how the lot may be used in the future. The Civil War Balloonists entry in the Historical Marker Database has not been updated to reflect the museum’s removal or the lot’s current use. The only option for visiting the monument is to park at the Ivor Massey Administrative Building on 5707 Huntsman Road.

Eric Atkisson is a retired Army National Guard officer and retired federal employee with 36 years of combined public service, including three wartime deployments to Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Iraq. He currently volunteers for the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, the Friends of Wilderness Battlefield, the Cedar Mountain Battlefield Foundation, and the Virginia National Guard Historical Foundation.

Endnotes:

Editor’s Note: Emerging Civil War’s Caroline Davis has previously published a three-part mini-series on the US Balloon Corps (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3), and guest author Jeff Ballard has also written a four-part mini-series on US balloon operations on the peninsula (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4)

[1] United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series III, Vol. III (Government Printing Office, 1899), 280.

[2] United States War Department, Report of Maj.-Gen. George B. McClellan, Aug. 4, 1863 (Sheldon and Company, 1864), 81.

[3] Eugene B. Block, Above the Civil War: The Story of THADDEUS LOWE, balloonist, inventor, railway builder (Howell-North Books, 1966), 103.

[4] Block, Above the Civil War, 96.

[5] James Longstreet, “Our March Against Pope,” The Century Magazine, November 1885 to April 1886 (The Century Co., 1886), 602.

[6] Thomas Paone, “The Most Fashionable Balloon of the Civil War,” National Air and Space Museum, accessed September 23, 2025, https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/most-fashionable-balloon-civil-war.

[7] E. P. Alexander, “Pickett’s Charge, and Artillery Fighting at Gettysburg,” The Century Magazine, November 1886 to April 1887 (The Century Co., 1886), 465.

Interesting, thank you for sharing!

Thanks for the Post, Erik. I have always been fascinated by Civil War ballooning and did not know that there was a monument to the balloonists at Seven Pines. Thanks.

Hey Eric, Professor Lowe employed two of his balloons down here on the lower Peninsula prior to hauling them up to the Richmond area. It seems that the relentless progress at the Richmond Airport has relegated the historic monument to a forgotten backwater location that does not improve its accessibility to Civil War travelers. I believe that exploitation of the history of Professor Lowe’s achievements would be better served if the monument were moved to the area where the balloons were initially utilized to observe the Confederate defenses along the Warwick River. That defensive line of the dammed up watercourse created a delay to McClellan’s advance to Richmond for over a month, and enabled Professor Lowe to log in many hours of flight time and observations. There are several appropriate locations in the Yorktown / Newport News area that promote the interpretation of the Civil War actions during the period from mid-March to May of 1862. Professor Lowe launched his two balloons in an area near Yorktown and the area near the Warwick County Courthouse. In fact, my personal recommendation would be to relocate the monument to the grounds of the Lee Hall Mansion, a Civil War era plantation home that has been faithfully restored by the City of Newport News to serve as a convenient destination for Civil war travelers to learn of the history of the Peninsula campaign. Check it out. It’s a winner!

If they followed through on your suggestion, I’d better go see it now while it’s still nearby!

Fascinating. Thank you for the post. I am reading a new study about Fair Oaks/Seven Pines and how close run a thing that battle really was for the U.S.

Your observation about the effect Lowe’s reconnaissance had on the crucial decision to move II Corps reinforcements to III Corps is spot on. Had Lowe’s report not sparked that move, McClellan might well have suffered a decisive defeat. The impact could have changed the course of the war.

Apologies for the what if – Is there a McClellan studier than can advise, had Little Mac suffered a bitter loss of III Corps at Seven Pines that early in the war, would the public damage to his reputation have made him more aggressive?

Didn’t George Custer participate in observation flights at Williamsburg? I did not see him listed on the Monument.

Is there a transcript of what is actually inscribed on the Monument? Any names?

I’m particularly interested in Lt. Col. Frederico Cavada, who worked as an artist sketching enemy positions from a balloon. He was captured at Gettysburg and later wrote one of the great Civil War memoirs about his time in Libby Prison. Illustrated with his own pen and ink drawings, and published while the war still raged, the book gave unique insights into the prisoner experience, and to the famous escape from Libby that he witnessed (but did not participate in).

He was a fascinating guy. Born a Cuban American, he was educated in Philadelphia and used his artistic gifts for the Union. After the war, he returned to Cuba, where he helped lead what is known as “The First Cuban Revolution”–against the Spanish dictatorship. He even wrote a book on guerrilla warfare. Captured by the Spanish he was executed, despite pleas for clemency by then President Grant. I found his grave, or maybe it was just a monument, in a cemetery in Key West.

I featured him and his drawings in my book “The Greatest Escape, a True American Civil War Adventure”, about the Libby breakout. But I could find nothing about his earlier service in the balloon corps. He barely mentions it in his memoir.

Any ideas?

My ancestor got to touch one of Lowe’s balloons at Dr. Gaines’ farm in June 1862, and talk with the engineers; he mentions it in his diary. They should have got the 5th Dimension to sing at the monument unveiling…

U.S. General Fitz John Porter experienced an unfortunate ballon ascent on the Peninsula. His tether snapped and he had a dangerous journey upwards and around the lines until he finally was able to bring down the balloon. The incident is memorialized on his statute in his hometown in New Hampshire.