The Battle of Mount Desert Island: Fear, Rumor, and Reality on the Maine Coast

ECW welcomes back guest author Peter Vermilyea.

The summer of 1863 had already been a tumultuous one when a vessel flying the Confederate flag appeared off the coast of Mount Desert Island, Maine, on the morning of July 23, 1863. Soon, the usually quiet waters erupted in violence. Cannon shots thundered across the waves, shaking windows and rattling buildings in Tremont.

Locals rushed to the shoreline, straining to see the source of the smoke that curled along the horizon. Children clung to their mothers, dogs barked, and men grabbed spyglasses, desperate for a glimpse of what was happening offshore. Witnesses later swore they saw a Confederate privateer exchange fire with a Union gunboat just miles from their homes. Yet the Navy Department never acknowledged the battle. No official record has been found, leaving historians to weigh rumor against silence. “Of course,” the New York Times mused in its reporting of the episode three weeks later, “everyone will enquire what all this means?”[1]

What happened off the coast of the Maine island destined to become a mecca for tourism remains largely a mystery. The answer to why this moment mattered, however, lies in the volatile and fraught atmosphere of the summer of 1863. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had just been thrown back from Gettysburg, but the ramifications of that victory were still unknown. John Hunt Morgan’s Rebel raiders terrorized Indiana and Ohio. Riots sparked by the new draft law engulfed New York City, Albany, Boston, Newark, and other Northern cities.

In Maine, the draft law prompted an enormous peace demonstration in Dexter, where some – almost certainly exaggerated – accounts claim 15,000 people turned out to voice their displeasure. Draft dodgers swarmed the forests of Aroostook County, and in Winter Harbor – perhaps twenty miles from the reported naval battle – the entire male population allegedly fled to Canada to avoid conscription.[2] Political divisions sharpened as Maine’s Union and Democratic conventions met, with Democrats threatening to withdraw support for the war.

New Englanders lived in a state of constant unease – and for the fishing villages that lined the Maine coast, the ocean, long a source of livelihood, was now a source of dread as Confederate raiders threatened their economic sustainability.

Those fears were justified. Less than a month earlier, Confederate naval officer Charles Read had staged a brazen raid on Portland Harbor. Commanding the captured fishing vessel Archer, Read infiltrated the harbor disguised as a fisherman, seized the revenue cutter Caleb Cushing, and attempted to disrupt Union shipping before being forced to surrender.[3] A petition from Maine residents two years earlier warned President Abraham Lincoln that Portland’s location made it vulnerable to attack, and Read’s raid proved them right.[4] This single event electrified Maine’s coast and convinced residents that Confederate raiders could strike anywhere, at any time.

State officials urgently petitioned Washington. Governor Abner Coburn warned that Maine’s shipping industry was “without the slightest protection from rebel pirates” and called for armed patrols.[5] The Portland Board of Trade passed a resolution demanding immediate naval protection.[6]

Even Salmon P. Chase, Secretary of the Treasury, weighed in, forwarding local complaints from customs officials to the Secretary of the Navy.[7] The federal government responded by ordering five warships to guard the coastline from Nantucket to Calais, but for many Mainers, the promise came too late to ease the fear already spreading through their communities.

In this context, the news from off the coast of Mount Desert Island was incendiary. Witnesses reported that a black-painted steamship had been lurking near Grand Manan Banks for days before closing on an unnamed U.S. gunboat around 10 a.m. on July 23. The two vessels reportedly traded fire for 45 minutes – with eyewitnesses counting between 53 and 56 shots – before the Union ship fled toward Southwest Harbor, the Confederate vessel in cautious pursuit until it neared shore.

Captain Meltiah Richardson of nearby Cranberry Island watched the action through a telescope “with perfect clarity.” George Booth of Tremont vouched for the truth of the account, and by that evening the town was alive with speculation.[8] To the people of coastal Maine, it meant that the war had come to their doorstep.

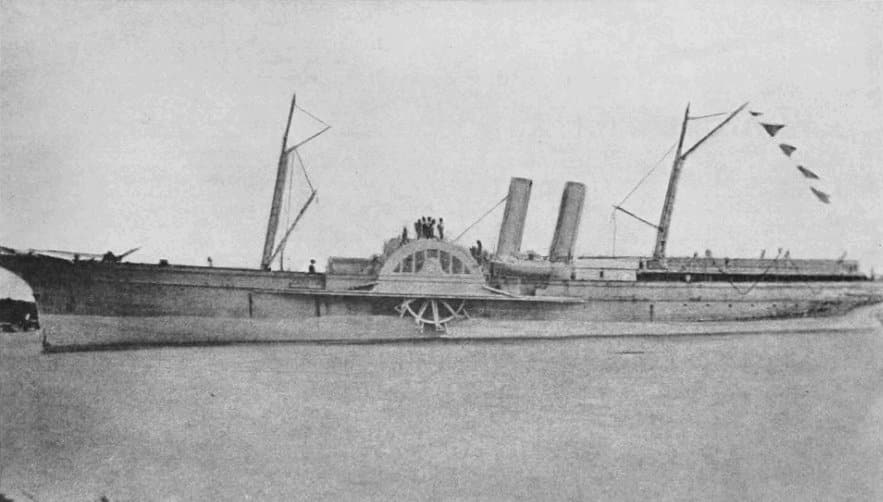

If the witnesses were right, what was the Confederate ship off Mount Desert Island? Despite the fact that most blockade runners were unarmed, the New York Times reported that some of the witnesses to the event suspected that she was Lord Clyde, a sleek Scottish-built side-wheel steamer that had been purchased in part by the state of North Carolina and renamed Advance.[9] Under the command of Lt. John J. Guthrie in July 1863, Advance became one of the most successful blockade runners of the war, completing twenty voyages and carrying millions of dollars worth of cotton to England while bringing back sorely needed military supplies. The United States Naval History and Heritage Command reports that Advance encountered forty Union vessels during her voyages.[10] Could one of those have taken place off the coast of Maine?

Historian Stephen R. Wise, in his superb book on blockade runners, estimates that Advance returned to North Carolina from Bermuda on July 24, 1863.[11] This would have made her presence off the Maine coast unlikely, but the vessel’s notoriety, and a New York Times article from July 17, 1863, that Lord Clyde (the paper had not yet reported the ship’s new name) was operating in the Atlantic, may have led those witnesses to speculate that they had seen the famed blockade runner.

Regardless of what may have happened in the cold waters of the Gulf of Maine, the psychological impacts of the Portland affair and the reports of the real or imagined Confederate raider were undeniable. The Maine Union Party passed resolutions urging more coastal defenses, and soon federal troops began building new batteries and posting additional forces along the shore. Seven companies of Maine Coast Guard infantry were raised and stationed at Eastport, Machiasport, Rockland, Belfast, and Calais.[12] Union blockading vessels were reassigned to northern waters, pulling resources away from the fight to strangle Confederate trade.

The Confederate threat did not vanish. In 1864, the cruiser Tallahassee destroyed fifteen ships off Maine’s coast during a three-day spree, forcing thirteen additional Union ships away from blockade duty in a desperate, but unsuccessful chase.[13] Insurance rates for Northern vessels skyrocketed, forcing shipowners to transfer nearly 300,000 tons of shipping to foreign registry – beginning a trend that permanently weakened the American merchant marine.[14]

The Mount Desert Island affair may never be fully explained, but it offers a rare glimpse into Northern psyche at a moment of crisis. Mainers did not need official confirmation to believe that Confederate raiders might strike their shores; they were already primed to expect it. With riots shaking cities, Confederate armies invading Pennsylvania, and naval raiders prowling the Atlantic, the sight of smoke on the horizon was enough to convince them that the enemy had arrived.

Whether the reports of the July 23 skirmish were truthful or exaggerated, the event’s significance lies in what it represented: the sense that the war had become terrifyingly close, that the line between home front and battlefront had blurred, and that even a rumor of battle could send an entire region into alarm.

Peter Vermilyea teaches history in Falls Village, Connecticut, and for the University of Connecticut. The co-director of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute teacher program, his most recent book, Litchfield County and the Civil War, was published in 2024.

Endnotes:

[1] “Mysterious Naval Battle,” The New York Times, August 13, 1863.

[2] Ruel H. Stanley and George O. Hall, Eastern Maine and the Rebellion: Being an Account of the Principal Local Events in Eastern Maine During the War (R. H. Stanley and Company, 1887), 270; “Great Fright at Winter Harbor,” Ellsworth American, August 22, 1862.

[3] David W. Shaw, Sea Wolf of the Confederacy: The Daring Civil War Raids of Naval Lt. Charles W. Read (Free Press, 2004),182-194.

[4] Kerck Kelsey, “Maine’s War Governor: Israel Washburn, Jr. and The Race To Save The Union,” Maine History 42, 4 (2006), https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal/vol42/ iss4/4, 249-250.

[5] Abner Coburn to Gideon Welles, June 30, 1863, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1894), ser. 1, vol. 2, 375.

[6] T. C. Hersey to Gideon Welles, June 30, 1863, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 2, 375.

[7] Salmon P. Chase to Gideon Welles, July 1, 1863, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 2, 376.

[8] “Mysterious Naval Battle,” The New York Times, August 13, 1863.

[9] “Mysterious Naval Battle,” The New York Times, August 13, 1863; Stephen R. Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running During the Civil War (University of South Carolina Press, 1991), 106.

[10] “Ad. Vance,” Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/confederate_ships/a-d-vance.html.

[11] Wise, 243. “From the Bermudas; Movements of the Blockade Runners – The Lord Clyde,” New York Times, July 17, 1863.

[12] Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Maine for the Year Ending December 31, 1863, (State of Maine, 1863), 43.

[13] See especially Gideon Welles to Samuel Corey, July 29, 1864, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 3, 129.

[14] “Maine History Online – 1850-1870 the Civil War – Page 4 of 5,” accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.mainememory.net/sitebuilder/site/903/page/1314/display?page=4; Rodney Carlisle, “Flagging-Out in the American Civil War,” The Northern Mariner, 22. 53-65.

Fascinating! I love these obscure incidents. Really widens your perspective on the war.

Thanks for sharing this anecdote Peter. I have it bookmarked to potentially get looked at in some of my own research down the line.

Peter, we were frequent visitors “Down East” while helping a Connecticut friend and his wife reconstruct an old MIT facility in East Machias into a boys and girls summer camp. First read/heard about the mysterious commerce raider while attending a niece’s wedding on Peaks Island in Casco Bay. And will always remember your courtesy and erudition during our Lincoln mini seminar in Glastonbury in 2009!

We moved to MDI in 2016 after we retired; I bet few (if any) locals have heard of this story. I may have to repost the article on a couple of MDI FB pages…Thank You for the research!